Open your high school biology textbook, and you will likely find a neat, tidy list. It probably tells you that for something to be considered "alive," it needs to do specific things: eat, grow, reproduce, and react to its environment. It’s a checklist. If you tick the boxes, you are alive. If you don’t, you are a rock, or water, or a piece of plastic.

For centuries, we have been comfortable with this binary. Life is on one side; non-life is on the other.

But recently, nature has decided to throw that rulebook into a shredder.

New discoveries are forcing scientists to scratch their heads and ask a question that sounds like it belongs in a philosophy class rather than a lab: What actually is a living thing? We are finding microscopic entities that act like ghosts, stealing bodies to survive. We are building "robots" made entirely of living flesh that exist in a weird limbo—a "Third State" that is neither alive in the traditional sense nor dead.

This article will take you on a journey into the gray areas of biology. We aren’t just talking about weird animals; we are talking about things that challenge the very definition of existence.

The Lazy Hacker: Candidatus Sukunaarchaeum mirabile

Motivation: Why Should We Care About Slime?

You might wonder why a microscopic speck found in a murky hot spring matters to you. Here is the reason: it breaks the fundamental rules of evolution. Usually, we think of evolution as a ladder. Things get more complex, smarter, and bigger. But nature is tricky. Sometimes, the best way to win the game of life is to stop playing by the rules entirely.

Value: The Art of Reductive Evolution

Meet Candidatus Sukunaarchaeum mirabile. It’s a mouthful to say, so let’s call it Sukuna.

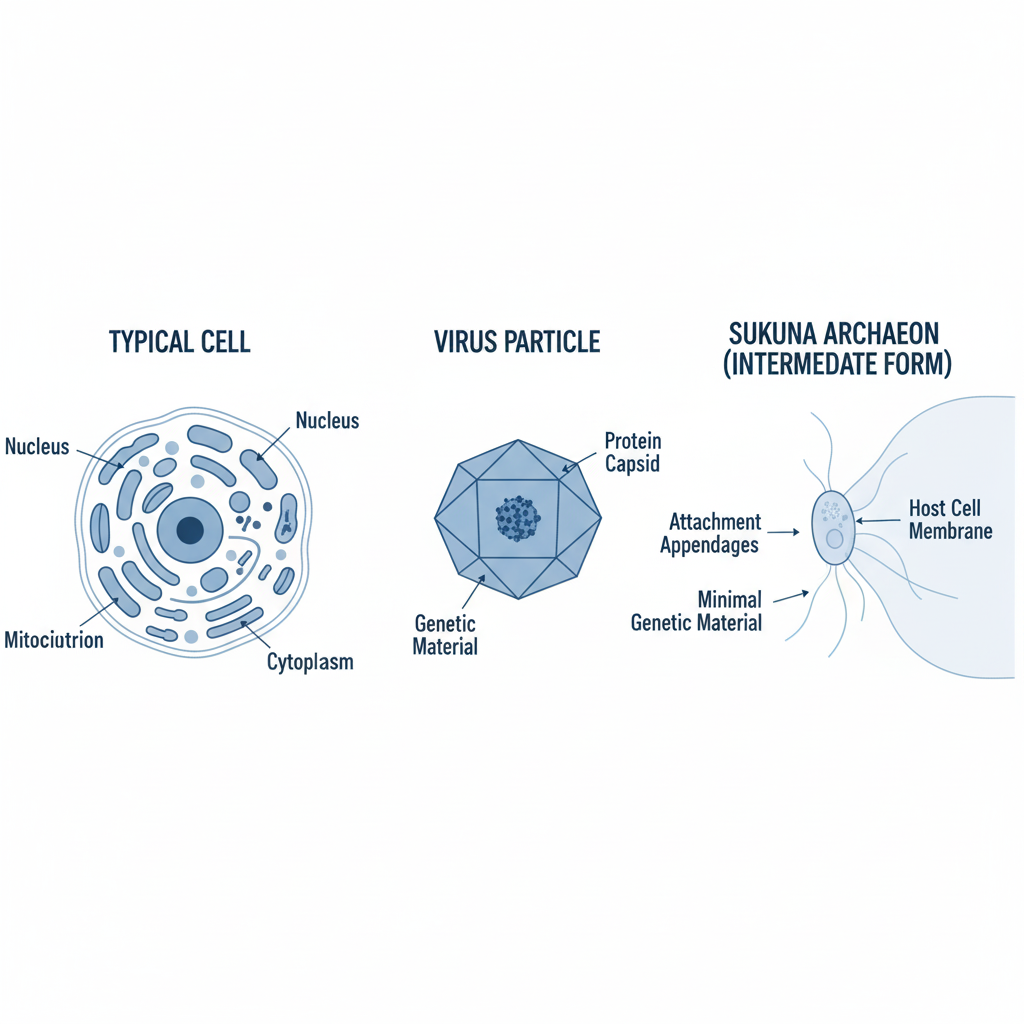

Sukuna is an archaeon. Archaea are single-celled organisms that look a lot like bacteria but are actually very different genetically. They are tough, ancient survivors often found in extreme places like volcanoes or deep-sea vents. But Sukuna is different. It is an evolutionary dropout.

Most cells are independent factories. They have the machinery to make their own proteins, generate energy, and copy their own DNA. Sukuna, however, has thrown all that machinery away. Through a process called reductive evolution, it has stripped itself down to the absolute bare essentials.

It cannot make its own energy. It cannot build its own parts. It is barely a cell at all.

Connection: The Ultimate Freeloader

Imagine a neighbor who moves into your house. But they don’t just sleep on the couch. They sell their own lungs, stomach, and heart because they figure they can just hook tubes up to yours and use your organs instead.

That is Sukuna. It attaches itself to another archaeon (a host) and literally siphons off what it needs. It has become a parasite so extreme that it is blurring the line between a living cell and a virus.

Execution: The Viral Strategy

This is where the classification gets messy. Viruses are usually considered "non-living" because they cannot reproduce without hijacking a cell. Sukuna is technically a cell—it has a cellular structure—but it behaves almost exactly like a virus.

- It lacks independence: Separated from its host, it is helpless.

- It has a tiny genome: It has deleted the genes for basic life functions.

- It is a hybrid: It represents a bridge. It shows us that "virus" and "cell" might not be two different buckets, but opposite ends of a sliding scale.

The Third State: Synthetic Biobots and Zombie Cells

Motivation: Frankenstein Was onto Something

If Sukuna is a natural oddity, what happens when humans start meddling? We usually think of death as the end. When an organism dies, its cells die, and that’s it. But what if cells from a dead creature could be rebooted, not as the original animal, but as something entirely new?

Value: Defining the "Third State"

This isn't science fiction. It is the concept of the "Third State" of existence.

Scientists have discovered that cells have a hidden potential. If you take skin cells from a deceased frog embryo and place them in a specific environment, they don't just die. They reorganize. They cluster together. They start to move.

These are called Xenobots (named after the frog Xenopus laevis).

- They move: They use tiny hairs (cilia) to swim.

- They heal: If you cut one in half, it stitches itself back together.

- They work together: They can push particles around in a dish.

- They replicate: In a very loose sense, they can gather loose cells to build "babies."

Connection: Not Robot, Not Animal

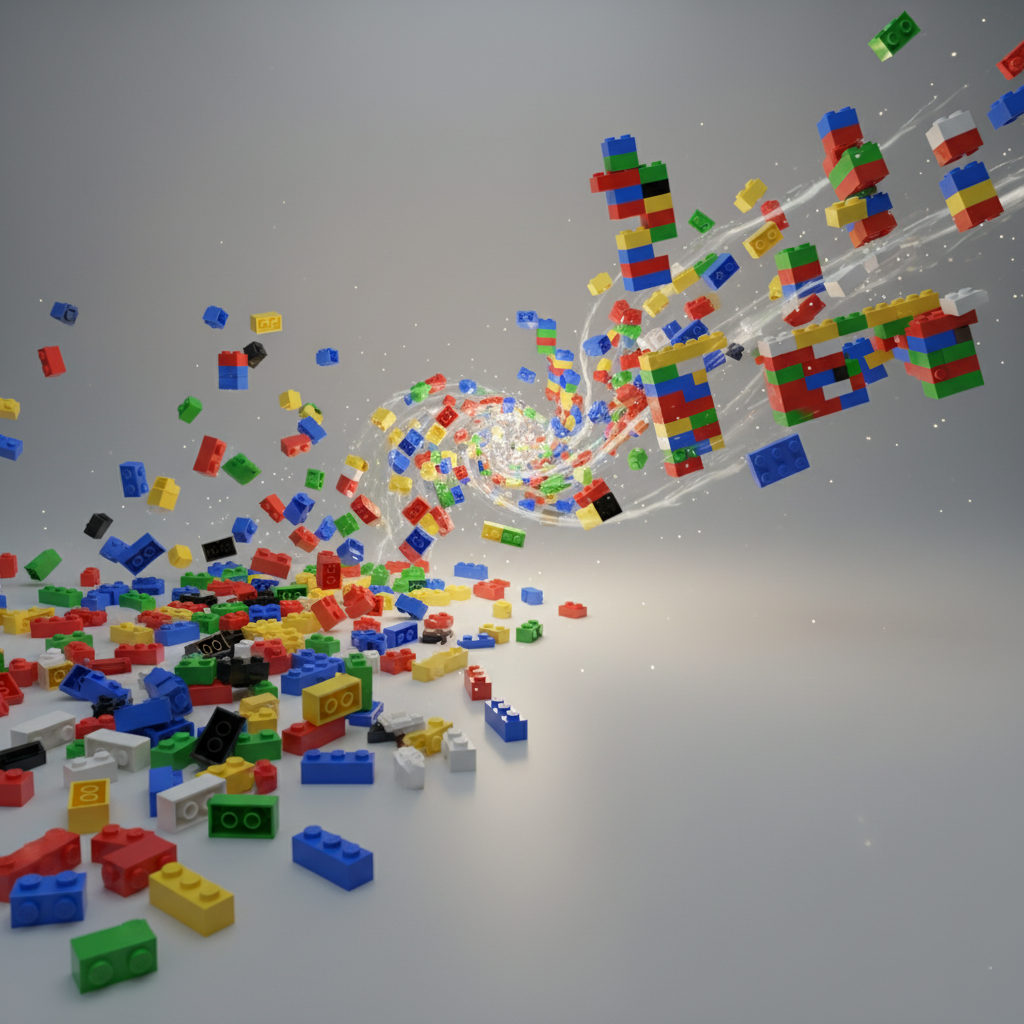

Think about a Lego castle. If you smash the castle, you have a pile of bricks. The castle is "dead." But the bricks are still fine. If those bricks suddenly stood up and started building a bridge on their own, you would be terrified.

That is a Biobot. The "frog" is gone. The genetic instructions to build a frog are ignored. The cells are improvising. They are existing in a state that is distinct from life (they aren't growing into a frog) and distinct from death (they are metabolically active and moving).

Execution: The Future of Medicine?

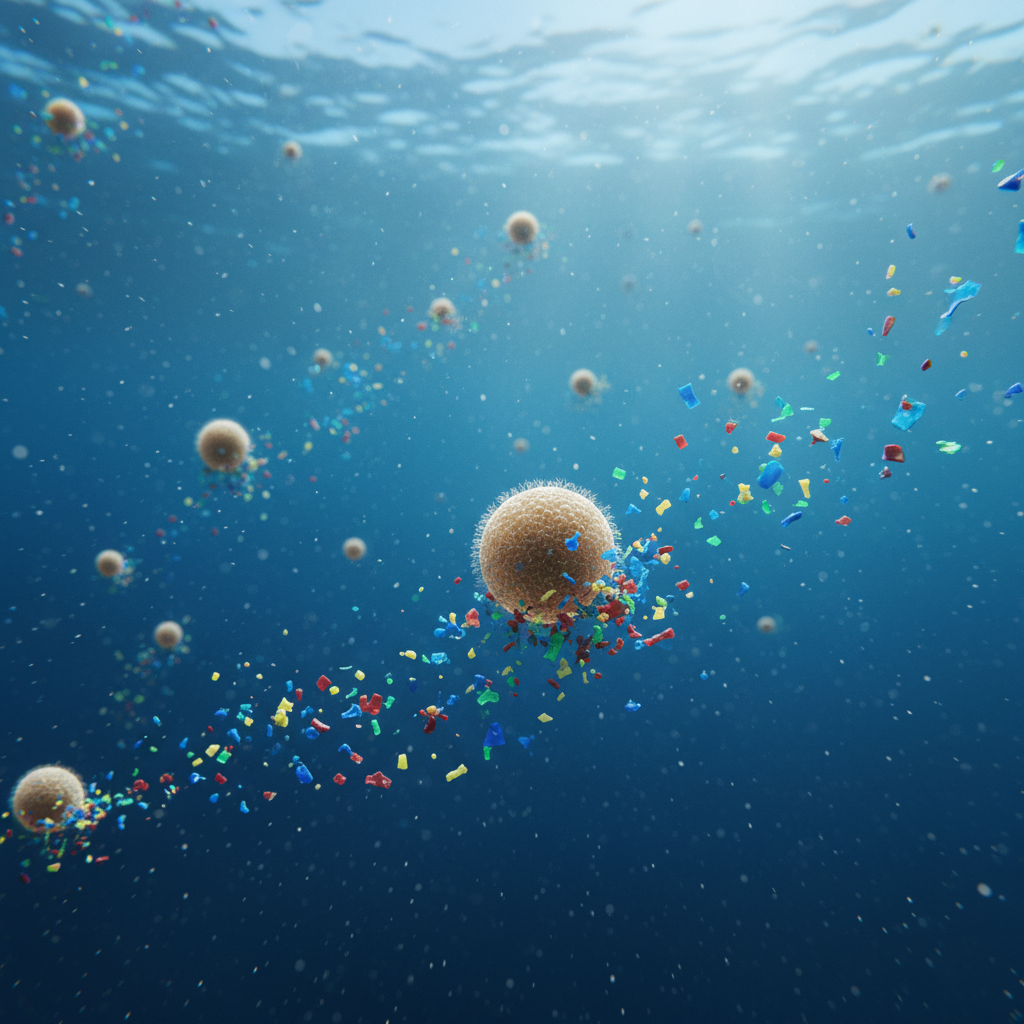

Why does this matter? Because these aren't made of metal or plastic. They are biodegradable.

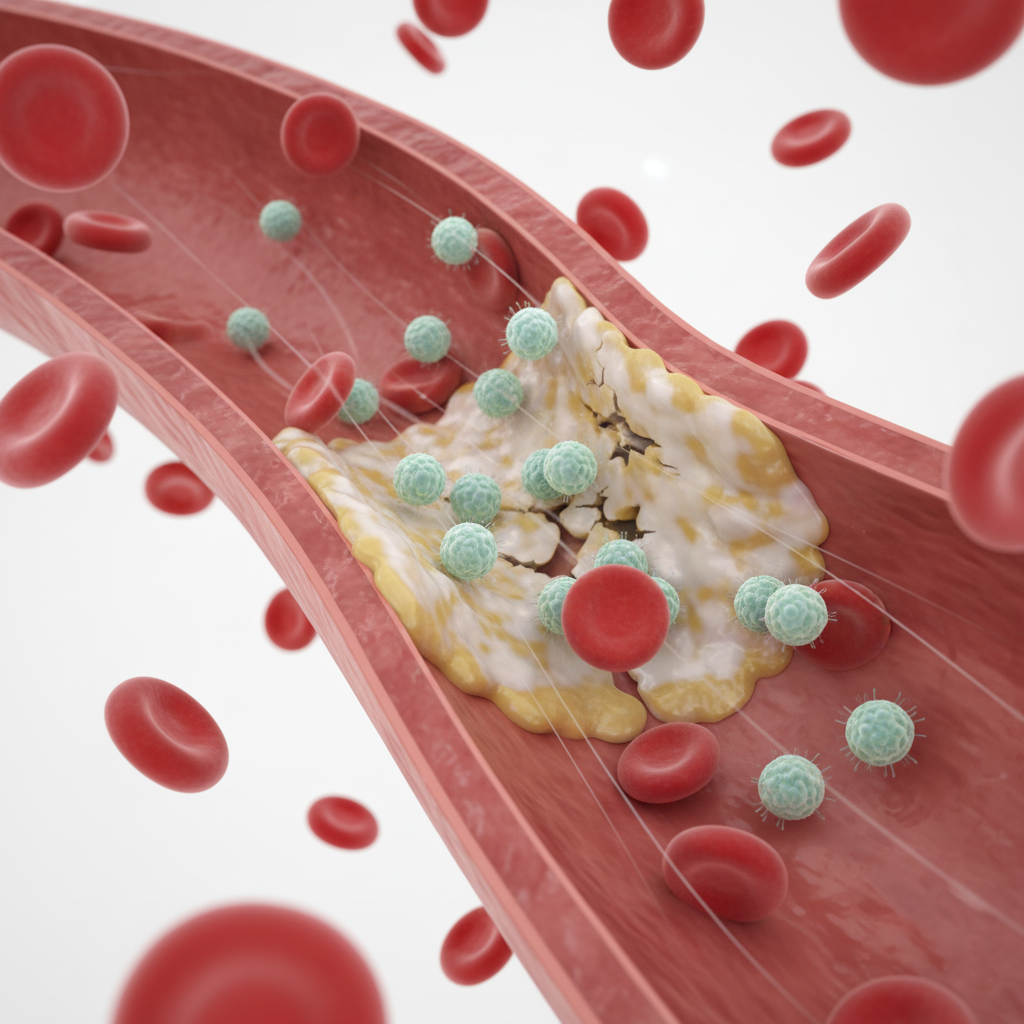

- Actionable Insight: In the future, we might inject biobots into a patient to scrape plaque out of arteries.

- The Benefit: Because they are made of patient-compatible cells, the body won't reject them. And when they are done, they just dissolve. No surgery, no metal waste.

Scientific Context: The Crumbling Wall Between Life and Non-Life

Motivation: The Rules Are Broken

We need to zoom out. Why are Sukuna and Biobots causing such a headache for biologists? It’s because our definition of life is based on "Established Criteria."

Value: The Standard Checklist (And Why It Fails)

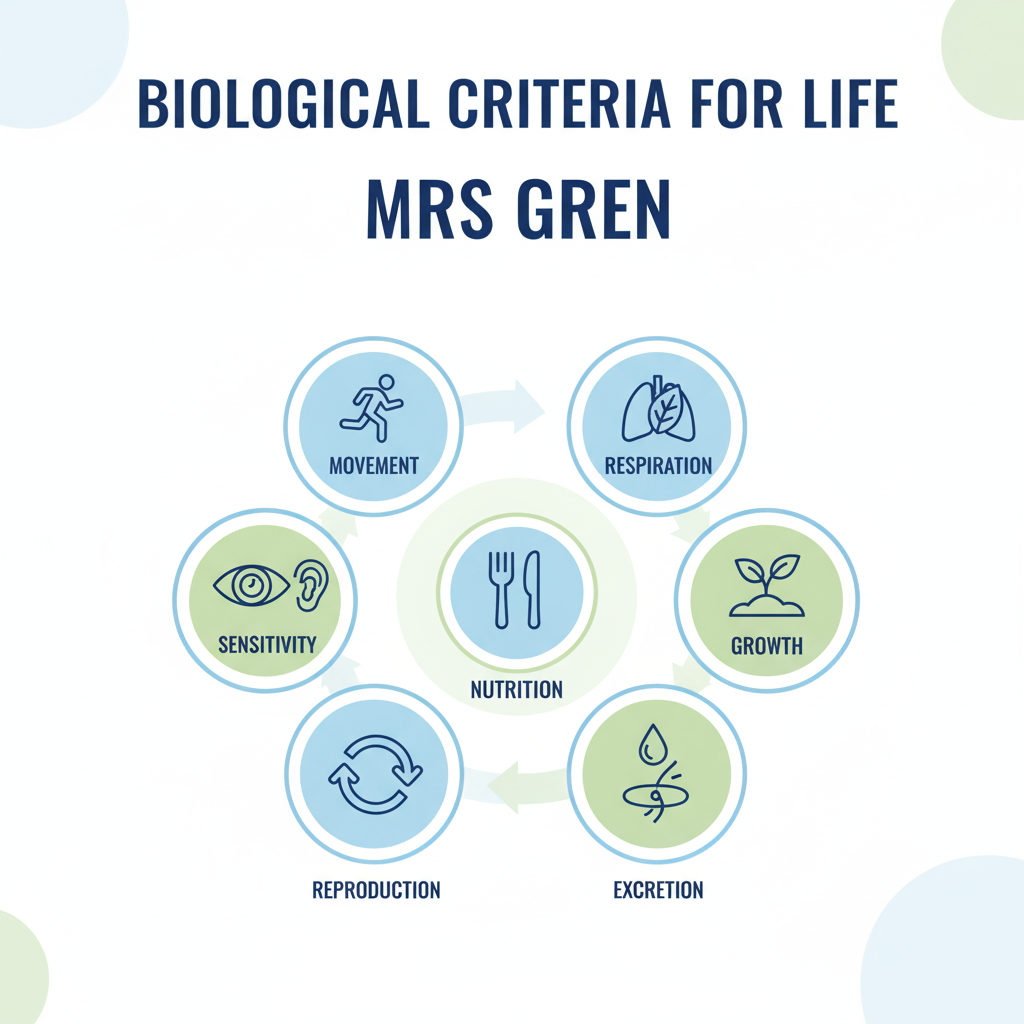

Classically, biology uses a few key criteria to define life (often remembered by acronyms like MRS GREN):

- Metabolism: Can it consume energy to maintain itself?

- Reproduction: Can it make copies of itself?

- Response to Stimuli: Does it react if you poke it?

- Homeostasis: Can it keep its internal environment stable?

- Evolution: Does it change over generations?

The Boundary Cases:

- Viruses: They have DNA or RNA. They evolve. But they have zero metabolism. They are basically crystals until they touch a cell. Are they alive? Most scientists say "no," or "sort of."

- Biobots: They have metabolism. They respond to stimuli. But they have no evolutionary future. They won't evolve into "better" biobots naturally. They are a physiological dead end.

- Sukuna: It has lost the ability to do almost all of this independently, yet it evolved from something that could.

Connection: The Spectrum of Aliveness

We try to put nature into boxes because the human brain likes categories. We want to know if the thing under the microscope is a friend (life) or a rock (non-life).

But nature prefers a spectrum. Think of color. We have "Red" and "Yellow." But where exactly does Orange stop being Orange and start being Red? There is no sharp line. Life is the same. There is a long, foggy road between simple chemistry and a complex human being. Sukuna and Biobots are parked right in the middle of that road.

Synthesis: We Need New Words

Motivation: The Language Barrier

The biggest problem we face right now isn't the science; it's the linguistics. Our words are failing us. When we call a Biobot a "robot," people think of Terminator. When we call Sukuna a "bacterium," we imply it’s independent.

Value: Biological Classification 2.0

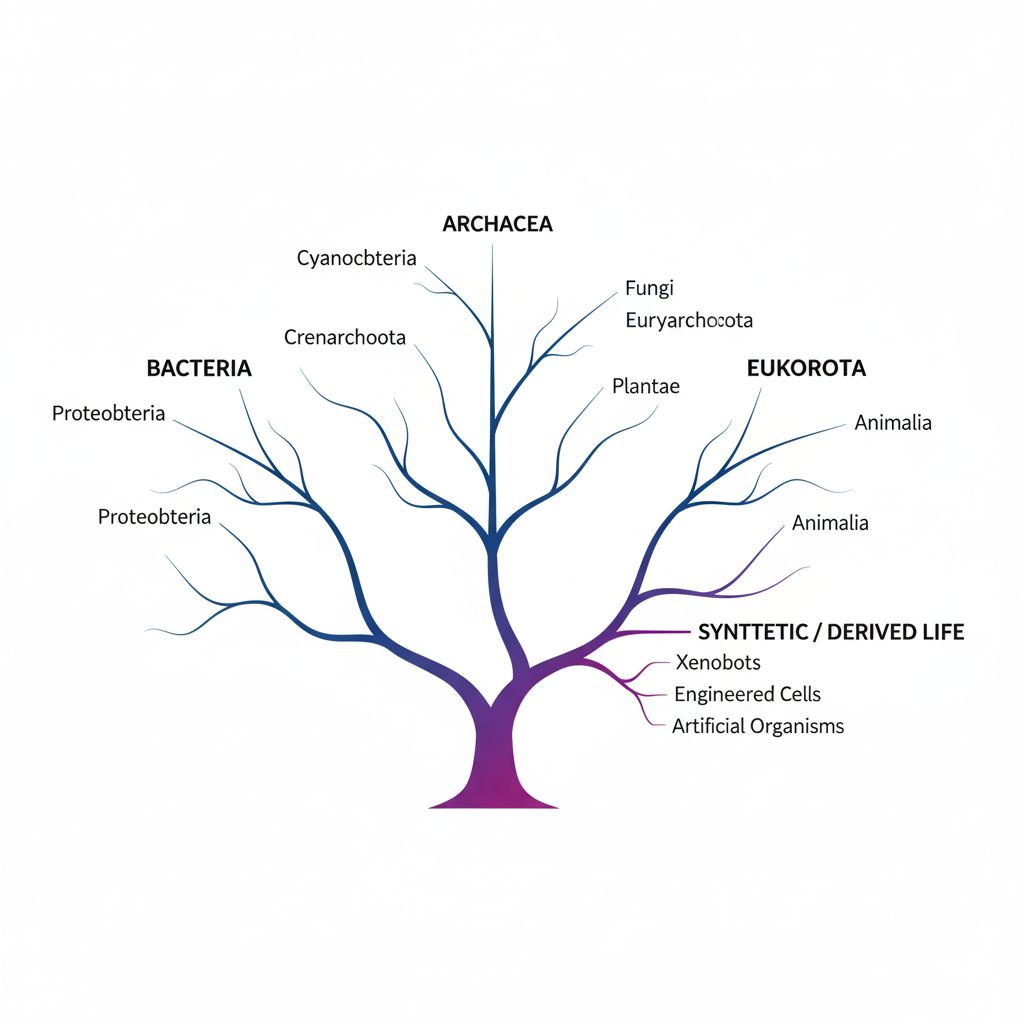

We are witnessing a shift in how we understand biology. We are moving away from looking at the organism (the whole animal) and looking at the agency of the cell.

- Cellular Agnosticism: We are learning that cells are not just bricks in a wall. They are intelligent agents. Even when the organism dies, the cells retain "life" capabilities.

- The "Third State" Definition: We need a formal category for "Biological entities derived from dead organisms that possess new functions."

Execution: How We Move Forward

Science evolves by admitting what we don't know. Here is how the scientific community is tackling this:

- Redefining Death: Death is not an event; it is a process. Biobots prove that "organismal death" does not mean "cellular death."

- New Taxonomies: We may soon see a new branch on the Tree of Life. We have Eukaryotes (animals/plants), Prokaryotes (bacteria), Archaea... and perhaps a new branch for "Synthetic/Derived Biological Entities."

Takeaway: The next time you look at a puddle, or a leaf, or even your own hand, remember: Life isn't a simple "On/Off" switch. It is a complex, beautiful, and sometimes terrifying dimmer switch.

FAQ: Questions You Were Too Afraid to Ask

Q: Are Biobots dangerous? Could they take over? A: No, not currently. Biobots have no brain and no desire to conquer. They live in petri dishes and usually die after a few weeks once their energy stores run out. They are more like wind-up toys made of cells than independent creatures.

Q: Is the Sukuna microbe a virus? A: Not technically. It still has a cell structure (a membrane and ribosomes) that viruses lack. However, it acts exactly like a virus by stealing resources. It sits in a gray area between a cell and a virus.

Q: Can humans enter the "Third State"? A: While individual human cells (like HeLa cells used in research) can live on after a person dies, a whole human cannot enter this state. The "Third State" refers to cells forming new structures and functions, which human cells don't naturally do after death without extreme lab intervention.

Q: Why do scientists create things like Biobots? A: The goal isn't to play god, but to solve problems. Traditional robots are hard (metal/plastic) and can damage the human body. Biobots are soft and safe. They could be the future of drug delivery or cleaning up microplastics in the ocean.

Q: Does this mean "zombies" are real? A: In a microscopic sense? Sort of! If you define a zombie as "dead tissue moving around," then Biobots fit the description. But they don't eat brains—they mostly just swim in circles.

Conclusion

For a long time, we thought we had the universe figured out. We drew a circle and said, "Everything inside this is Alive, and everything outside is Dead."

But the universe is far more creative than that.

The discovery of Candidatus Sukunaarchaeum mirabile shows us that life can devolve, stripping itself down until it is barely distinguishable from a virus. The invention of Synthetic Biobots reveals that life can persist and transform even after the organism it belonged to has died, entering a mysterious "Third State."

These discoveries are not just cool facts for a trivia night. They are fundamental challenges to our understanding of reality. They force us to rewrite the dictionary, rethink our ethics, and accept that the boundary between the living and the non-living is not a wall—it’s a bridge. And we are just starting to walk across it.