Imagine looking out at the ocean. You see waves, ships, and a whole lot of water. What if you saw farms? Not fish farms, but vast, green fields of rice, swaying in the salty breeze. Now, picture a country with 1.4 billion people to feed. A country that has about 20% of the world's population but less than 10% of its farmable land. That country is China, and for them, food isn't just a meal; it's a matter of national security. This desperate need has sparked one of the most exciting and misunderstood agricultural stories of our time: the tale of "seawater rice."

We’ve all seen the headlines. "China Grows Rice in Seawater!" "A Miracle Crop to End World Hunger!" It sounds like science fiction. It paints a picture of scientists creating a super-plant that can be grown directly in the sea, unlocking 70% of the Earth's surface for agriculture.

But is that really what's happening?

This isn't a simple story of a magic seed. It’s a complex, decades-long journey that weaves together genetics, economics, national strategy, and environmental engineering. The motivation is simple: survival. The value lies in turning useless, salty land into a breadbasket. The connection is to the most basic human need—food. And the execution? Well, that’s where the "miracle" gets complicated, and frankly, a lot more interesting.

Let's deconstruct the hype, dig into the real science, and understand the true narrative of China's ambitious plan to farm the salt.

Executive Summary: Deconstructing the Core Claim

First, let's get one thing straight. The term "seawater rice" is a brilliant piece of marketing, but it's deeply misleading.

This rice is not grown in the ocean.

You can't just scatter these seeds off the coast of Shanghai and expect a harvest. If you did, you’d get exactly what you’d expect: dead plants. The "seawater rice" story is not about farming the sea; it's about reclaiming the land ruined by the sea.

The real name for this crop is salt-alkali-tolerant rice.

This is a category of rice strains specifically bred to survive and produce grains in soil with high salt and alkaline content. Where do you find this soil? You find it in coastal tidal flats, inland deserts, and areas where overuse of irrigation has brought natural salts to the surface. This is land that is, for all practical purposes, dead. You can't grow normal crops, you can't build on it easily, and it's expanding every year due to climate change and rising sea levels.

These new rice strains are tough, but they aren't that tough. They are typically irrigated with brackish water—a mix of freshwater and seawater—or grown in soil that has a salt content of about 0.3% to 0.6%. For context, full-strength seawater is about 3.5% salt.

So, the core claim isn't "we can farm the ocean." The core claim is, "We have developed a tool to turn millions of acres of barren, salty wasteland into productive, food-growing fields." This distinction is critical. It’s the difference between a fantasy and a revolutionary, real-world innovation.

The Strategic Imperative: China's National Food Security

Why pour billions of dollars and decades of research into this? To understand the motivation, you have to understand China's core vulnerability: food.

The 1.4 Billion Mouths Problem

China is a superpower, but it's a superpower that walks a tightrope. Its massive population relies on a surprisingly small amount of good farmland. For decades, this farmland has been under constant attack.

- Urbanization: Megacities are sprawling outwards, paving over fertile fields to build factories, apartment blocks, and highways.

- Pollution: Industrial runoff has contaminated large tracts of soil and water.

- Climate Change: Rising sea levels are pushing saltwater further inland, poisoning coastal farms. Increased droughts and floods are making farming more unpredictable.

This has led to a single, overriding national policy: food self-sufficiency. China's leaders know that a nation dependent on other countries for its food supply is a nation that can be controlled. They must be able to feed themselves.

The "Red Line" and the Wasteland

To protect its food supply, the government established a "red line" of 120 million hectares (about 300 million acres) of arable land that must be protected at all costs. But with that line constantly under threat, the only solution is to create new farmland.

This is where the "seawater rice" comes in. China has an estimated 100 million hectares of saline-alkali "wasteland." That's an area almost the size of Egypt. For generations, this land was considered a write-off.

But what if it wasn't?

If China could make even a fraction of that land productive, it would be a game-changer. It would be like discovering a new, fertile continent within its own borders. This rice isn't just a crop; it's a geopolitical tool, a buffer against famine, and a pillar of a national survival strategy.

The Science of Salt-Tolerant Rice

So, how do you teach a plant that evolved over millennia in freshwater marshes to survive in a salty field? You can't just talk to it. You have to rewrite its genetic code.

Why Salt Kills Most Plants

To appreciate the solution, you have to understand the problem. Salt is a plant-killer in two ways.

- Dehydration: Salt is "thirsty." Through a process called osmosis, salt in the soil actually sucks the freshwater out of a plant's roots. The plant literally dies of thirst, even though it's sitting in water.

- Toxicity: Salt is made of sodium and chloride. In high concentrations, these ions are toxic. They get inside the plant's cells and disrupt all its internal machinery, like throwing a wrench into an engine.

Building a Super-Rice: The Genetic Quest

This technology wasn't invented overnight. It's the life's work of generations of scientists, most notably Yuan Longping, the "Father of Hybrid Rice," who began this quest in the 1980s.

The process is like a massive genetic scavenger hunt.

- Step 1: Find the Wild Survivors. Scientists didn't start in a lab. They went to coastal mangrove swamps and salty marshes. They looked for wild strains of rice that were, against all odds, already surviving in these harsh environments. These wild plants were tough, but they produced tiny, awful-tasting grains. They had the survival genes, but not the food genes.

- Step 2: Cross-Breeding (The Old-Fashioned Way). For decades, scientists painstakingly cross-bred these tough, wild rice plants with high-yield, delicious domestic rice. It's like breeding a strong, stubborn mule with a fast, sleek racehorse. You do it over and over, generation after generation, trying to get a new plant that has the strength of the mule and the speed of the racehorse.

- Step 3: Gene Editing (The Modern Way). Today, with technology like CRISPR, this process is much faster. Scientists can identify the specific genes that give the wild rice its superpower.

What Do These Super-Genes Do?

Scientists found that salt-tolerant rice plants have two main tricks that normal rice doesn't.

- Exclusion (The Bouncer): The roots of these plants are better "bouncers." They have enhanced filters that are more effective at physically blocking the toxic salt ions from getting into the plant in the first place.

- Sequestration (The Toxic Waste Dump): Some salt inevitably gets in. But instead of letting it float around and cause damage, these plants have a genetic mechanism to trap the salt ions. They capture them and lock them away in special storage compartments in the cells (called vacuoles), where they can't do any harm. It's the biological equivalent of putting toxic waste in a sealed barrel and sticking it in the basement.

This combination of genetic traits, refined over 40 years, has resulted in strains that can thrive in conditions that would kill 99% of other rice varieties.

Production, Yield, and Scale: From R&D to Deployment

A plant that can survive salt is one thing. A plant that can produce enough food to be worthwhile is another. This is where the laboratory meets the harsh reality of the field.

The Promise vs. The Reality of Yields

You will often see media reports of "seawater rice" test plots with massive yields, sometimes claiming they produce more than conventional rice. This is usually hype.

The real goal is not to beat premium rice grown on premium land. The goal is to get a commercially viable yield on useless land.

Think about it: the yield of a normal crop on a salty mudflat is zero. If a farmer can suddenly harvest 3 or 4 tons of rice per hectare on that same land, that is an infinite improvement. That's the value proposition.

In places like the tidal flats of Qingdao or the "northern great wasteland" in Heilongjiang, farms are now successfully growing this rice at scale. The initial target was 4.5 tons per hectare. Many test farms have already surpassed this, reaching 6, 8, or even 9 tons in ideal conditions. This is a staggering success.

It's Not Just Planting, It's Ecosystem Engineering

The execution of this project is where it gets truly brilliant. The Chinese aren't just planting rice. They are using the rice as a pioneer species to fix the broken land itself.

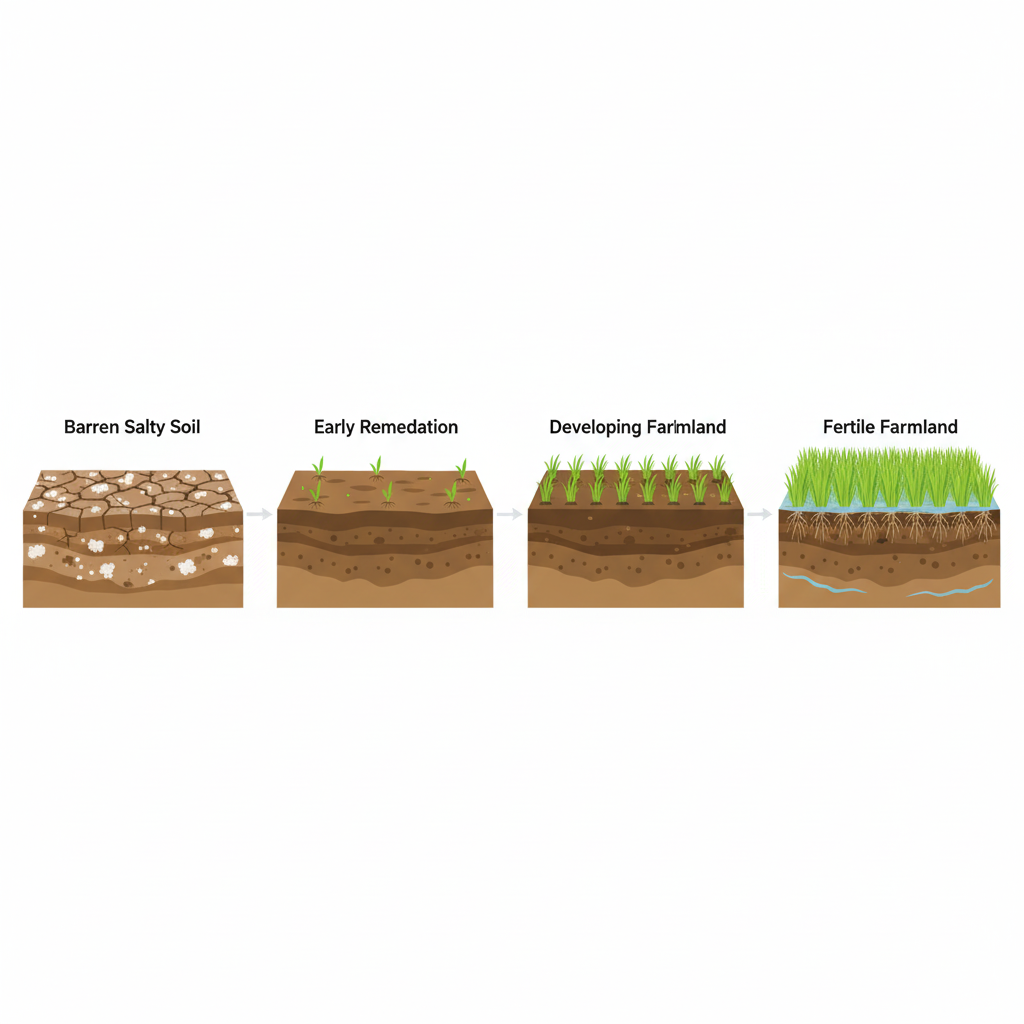

This is a multi-year process:

- Land Transformation: First, the barren, salty land is leveled and new, advanced irrigation systems are built to carefully manage the water's salt content.

- Planting the Pioneer: The salt-tolerant rice is planted. As it grows, its roots break up the dense, compacted salty soil.

- Soil Improvement: When the rice is harvested, the stalks and roots (organic matter) are tilled back into the ground. This organic matter begins to build a new layer of topsoil.

- Desalination: The rice plants themselves act like tiny, natural desalination pumps. They absorb salt from the soil and store it in their stalks (which are then removed), slowly but surely reducing the overall salinity of the earth.

After just two or three years of this cycle, the soil is fundamentally changed. It becomes less salty, richer in nutrients, and more stable. The land is "reclaimed." Farmers can then switch to growing less-tolerant (but higher-yield) crops like soybeans, corn, or even conventional rice.

The "seawater rice" is the first-wave soldier, the pioneer that makes the land safe for everything that follows.

Economic and Commercial Viability

This all sounds amazing, but is it affordable? Can a farmer actually make a living doing this?

The High Cost of Setup

Let's be clear: this is not cheap. The initial investment is massive. Leveling millions of acres of tidal flats and building high-tech irrigation systems costs a fortune. This is why the project is state-driven. The Chinese government is pouring billions in subsidies into this because the strategic value of food security is priceless, even if the commercial value is initially low.

Creating a Premium Niche Market

However, the "seawater rice" has a clever commercial angle, too.

The rice itself (with brand names like "Yan-Feng 47") isn't just sold as cheap bulk grain. It’s marketed as a premium, healthy, organic product.

- The Flavor: Because it's grown under stress in mineral-rich water, the rice has a unique, nutty flavor and a chewier texture.

- The Nutrition: Marketers claim it's higher in minerals like calcium, potassium, and other micronutrients than conventional rice.

- The "Clean" Factor: Because it's grown on "new" land far from traditional industrial or agricultural pollution, it's often seen as purer and cleaner.

This marketing allows the rice to be sold in high-end supermarkets for as much as 10 times the price of standard rice. This high price point helps farmers offset the lower yields and high startup costs, creating a sustainable business model that exists alongside the national strategic goal.

Quality, Nutrition, and Environmental Impact

A project this massive is guaranteed to have side effects. Is this rice good for you, and is it good for the planet? The answer is a classic "it's complicated."

A Question of Taste and Health

As mentioned, the taste and texture are different. Some people love the chewy, hardy feel. Others might find it too rustic compared to the soft, fluffy white rice they're used to. It's like the difference between a dense, whole-grain artisan loaf and plain white bread.

Nutritionally, the claims of higher minerals are plausible but still being studied. The key takeaway is that it is a viable staple food. It delivers the carbohydrates and energy that billions of people rely on, but from a source that never existed before.

The Environmental Equation: Good or Bad?

This is the most important question. Are we solving one problem just to create another?

The Good:

- Land Reclamation: This is the obvious win. It turns barren land into productive farmland and a living ecosystem.

- Carbon Sink: New rice paddies are wetlands. Wetlands are excellent at capturing and storing carbon (CO2) from the atmosphere, helping to fight climate change.

- Habitat Creation: These new coastal farms quickly become new habitats for birds, insects, and aquatic life, increasing local biodiversity.

The Bad and The Complicated:

- Freshwater Use: This is the biggest concern. These strains are salt-tolerant, not salt-exclusive. They still need to be irrigated with brackish water, which means large amounts of precious freshwater are used to dilute the seawater. In a water-scarce country like China, is this a sustainable use of a limited resource? The race is on to develop new strains that can tolerate even higher salinity to reduce this freshwater dependency.

- Methane Emissions: Rice paddies, unfortunately, are one of the world's largest man-made sources of methane, a greenhouse gas over 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide. As these paddies decompose organic matter, they release methane into the air. This environmental cost offsets some of the carbon sink benefits.

- Coastal Ecosystem Impact: What was on this "wasteland" before? Was it a natural tidal marsh or a mangrove forest that was "in the way"? Great care must be taken to ensure these new farms aren't destroying existing valuable ecosystems to create new ones.

Concluding Synthesis: The True Narrative

So, what is the true story of "seawater rice"?

It’s not a miracle. It’s not science fiction. It’s a powerful, real-world example of human ingenuity driven by a desperate need.

The headline "China Grows Rice in the Ocean" is a myth. The true narrative is far more complex and impressive. It's a story of scientists unlocking the genetic secrets of wild plants. It's a story of engineers transforming dead, salty earth into living soil. And it's a story of a nation building a new line of defense against hunger.

This technology is not a magic bullet. It faces enormous challenges of cost, freshwater use, and environmental side effects. But it is an incredible success. It has proven that "wasteland" is just a matter of perspective. It has shown that land we once considered lost can be reclaimed.

This is a story that goes beyond China. Countries like Vietnam, Bangladesh, Egypt, and the Netherlands are all losing farmland to rising seas. The lessons being learned in China's salty fields could one day provide a blueprint for how the rest of the world adapts to a warmer, wetter, and hungrier planet.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. So, you definitely can't just plant this rice on a sandy beach? Absolutely not. A sandy beach has almost no nutrients and is washed over by full-strength seawater (3.5% salt). This rice is grown on stable, muddy, or clay-based soil (like a tidal flat or inland desert) that has a high salt content, and it's irrigated with carefully controlled brackish (partly fresh) water.

2. Does "seawater rice" taste salty? No. The plant's entire biological function is to block the salt (sodium ions) at the roots or lock it away in its stalks and leaves, not store it in the grain. The final rice grain tastes nutty and perhaps slightly savory, but it is not "salty."

3. Is China the only country doing this? While China's program is the largest and most famous, many other countries are also researching salt-tolerant crops. India, Pakistan, Egypt, and the Netherlands are all working on various strains of rice, wheat, and barley that can survive in more saline conditions.

4. Why not just build desalination plants to get freshwater and grow normal rice? Desalination (removing salt from seawater) is an option, but it is unbelievably expensive and energy-intensive. It is so costly that it is currently not economically viable for agriculture, which requires massive amounts of water. It is far cheaper and more scalable to adapt the plant to the water than it is to adapt the water to the plant.

5. What is the next step for this technology? The "holy grail" is to create a rice strain that can be irrigated with full-strength seawater, which would eliminate the need for freshwater. Scientists are working on this, but it is an incredibly difficult genetic challenge. The more immediate goal is to create strains that are even more tolerant, require less freshwater, produce higher yields, and release less methane.

The Final Takeaway

The challenge of feeding 1.4 billion people on a shrinking amount of land forced China to look at its "wasted" landscapes and ask, "What if?"

The "seawater rice" project is the answer. It’s a testament to the power of long-term, state-funded scientific research. It proves that our most challenging problems—food security, land degradation, climate change—will not be solved by a single, magical discovery. They will be solved by the slow, difficult, and brilliant work of a thousand small steps.

China isn't farming the sea... yet. It's teaching the land to drink from it. And in a world running out of freshwater, that might be the most revolutionary idea of all.