Have you ever looked up at the full moon, so bright it casts shadows, and wondered... could that power something? In our quest for 24/7 renewable energy, it’s a tempting idea. Imagine a world where our solar panels don't clock off at sunset but just keep on sipping power from the night sky.

It’s an idea so compelling that it’s sparked a persistent internet myth. You may have seen headlines claiming "New Moonlight Panel Beats Solar by 35%!" or articles promising a breakthrough in lunar energy. It sounds like science fiction come to life.

But here's the hard question: What does the science actually say?

When we peel back the layers of clickbait, we find a fascinating story. It’s a story about the staggering, almost unimaginable power of our sun. It's a story about the fundamental physics of how a solar panel really works. And, most importantly, it's a story about how a real, exciting scientific discovery got twisted by a game of "digital telephone" into a brilliant and believable hoax.

So, let's become energy detectives. We're going to investigate the case of moonlight power. We'll run the numbers, examine the physics, and find the real source of the myth. The truth is far more interesting—and weird—than the fiction.

The Difference Between a Fire Hose and a Leaky Faucet

To understand why "moonlight power" is a non-starter, we first need to grasp the fundamental difference between our two main celestial lights. We often think of them as "the big light" and "the small light," but that doesn't even begin to cover it. The disparity isn't just a difference in size; it's a difference in nature.

Solar Irradiance as the Photovoltaic Benchmark

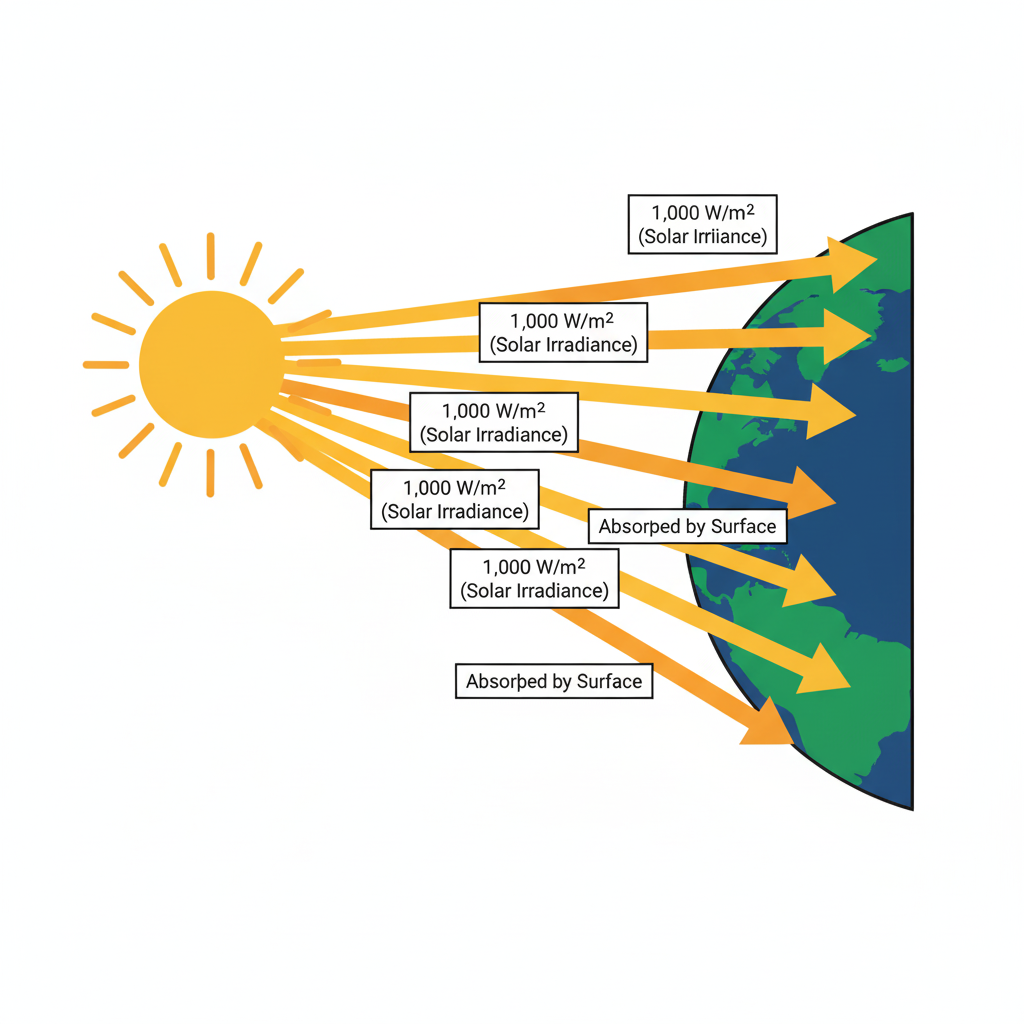

First, let's talk about the sun. The sun is a star, a gigantic, continuous nuclear fusion reactor. It’s blasting out its own energy in all directions. The amount of that energy that actually reaches the top of Earth's atmosphere is a measurement we call solar irradiance.

Scientists use this as the "gold standard" for testing solar panels. This value, often called the "solar constant" (though it varies slightly), is measured in watts per square meter (W/m²).

The Benchmark Number: On a clear day, at noon, when the sun is directly overhead, the surface of the Earth receives approximately 1,000 Watts of energy for every square meter.

Think about that. A single square meter—about the size of a large beach towel—is being hit with enough raw power to run a microwave oven, a high-end gaming PC, or ten old-fashioned 100-watt light bulbs. This is the fire hose of energy that photovoltaic (PV) technology was invented to capture.

The Nature and Intensity of Lunar Light

Now, what about the moon? Here’s the single most important fact: The moon does not produce any light of its own.

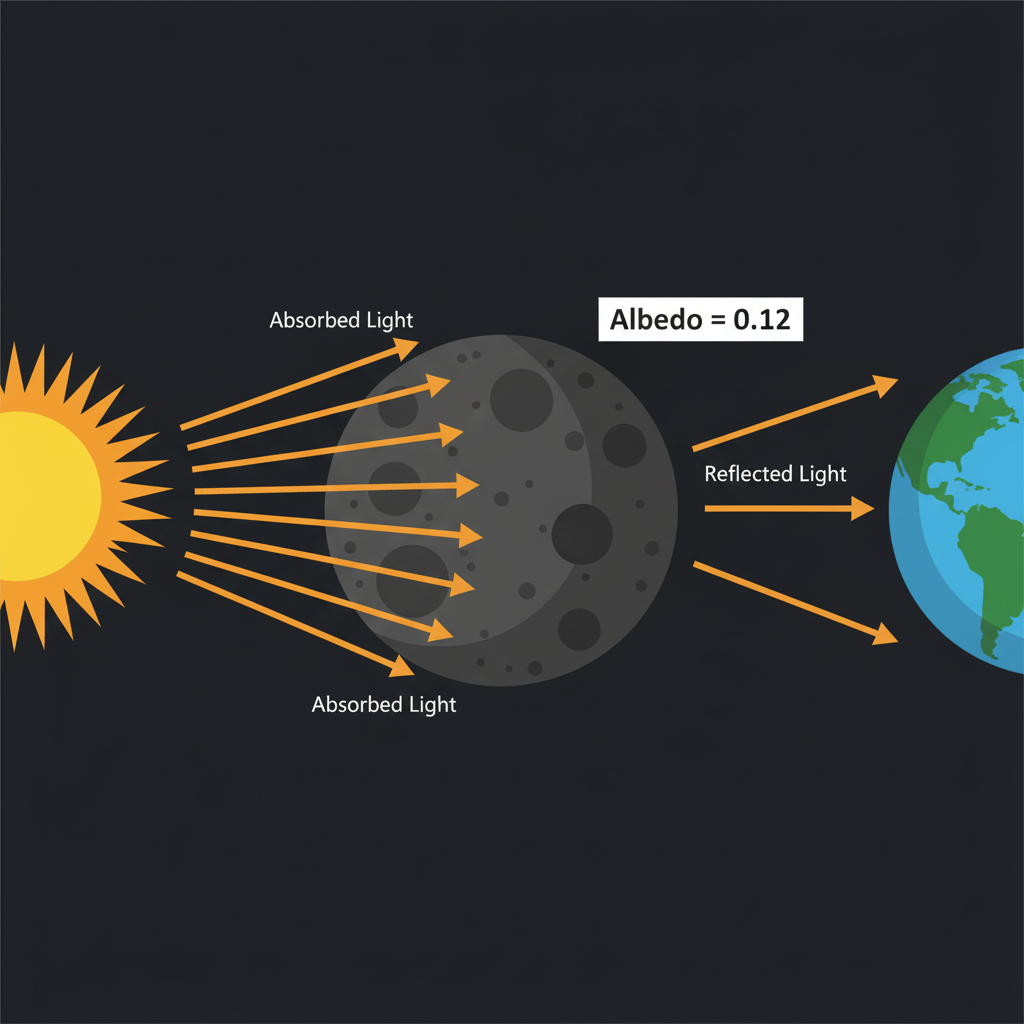

Every single speck of moonlight you’ve ever seen is just reflected sunlight. The moon is just a giant, rocky, dusty mirror in the sky. And as mirrors go, it’s a pretty terrible one.

The scientific term for an object's reflectivity is albedo. An albedo of 1 would be a perfect mirror, and an albedo of 0 would be perfectly black. The moon's average albedo is only about 0.12. This means it only reflects about 12% of the sunlight that hits it. The rest is absorbed and turns into heat.

What does 12% reflectivity look like? It’s not a shining, silvery beacon. The moon's surface is, on average, the color of dark, worn asphalt.

It only looks so bright to our eyes for one simple reason: it’s floating in a background that is pure, inky-black vacuum. Compared to the utter blackness of space, even a dim, asphalt-colored rock reflecting a tiny bit of sunlight seems dazzling.

A Quantitative Comparison of Irradiance

So, we have a fire hose (the sun) and a leaky, dirty mirror (the moon). Let's compare the numbers directly.

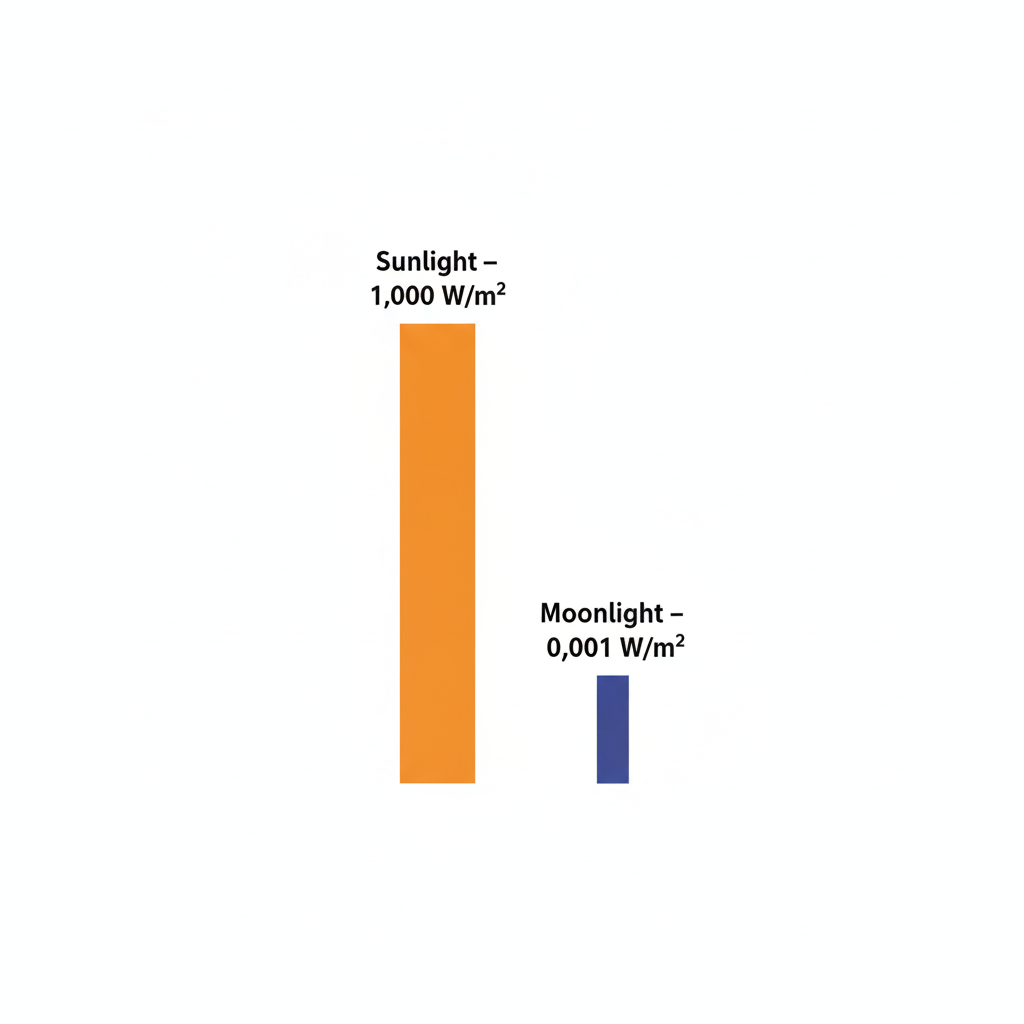

We already know direct sunlight is 1,000 W/m². What about the brightest possible full moon, on the clearest night, directly overhead?

The irradiance from a full moon is, on average, about 0.001 W/m².

Let’s write that out again.

- Sunlight: 1,000.000 W/m²

- Moonlight: 0.001 W/m²

This means that direct sunlight is not 10 times, 100 times, or even 1,000 times stronger than moonlight. It is one million times stronger. (Note: Some measurements put the sun at only 400,000 times brighter, but the point remains the same. The gap is colossal.)

Here's an analogy: If the energy from the sun was a $100 bill, the energy from the full moon would not even be a penny. It would be a tiny fraction of a single penny. It is, for all power-generation purposes, a rounding error.

The Scientific Utility of a Faint, Stable Source

This doesn't mean moonlight is useless to science. In fact, its faintness is a feature, not a bug. Because the moon has no atmosphere, its reflectivity is incredibly stable. It’s a constant.

Scientists and engineers use the moon as a calibration tool. They point ultra-sensitive telescopes and Earth-observing satellites at the moon to check their sensors. The moon is the perfect "cosmic candle"—a faint, predictable, and unchanging source of light that they can use to make sure their billion-dollar instruments are working perfectly.

It's an essential tool for observation. But for power? It’s just not in the game.

Why Your Solar Panel Ignores the Moon

"Okay," you might be thinking, "it's weak. But it's not zero. Can't we get something from it?"

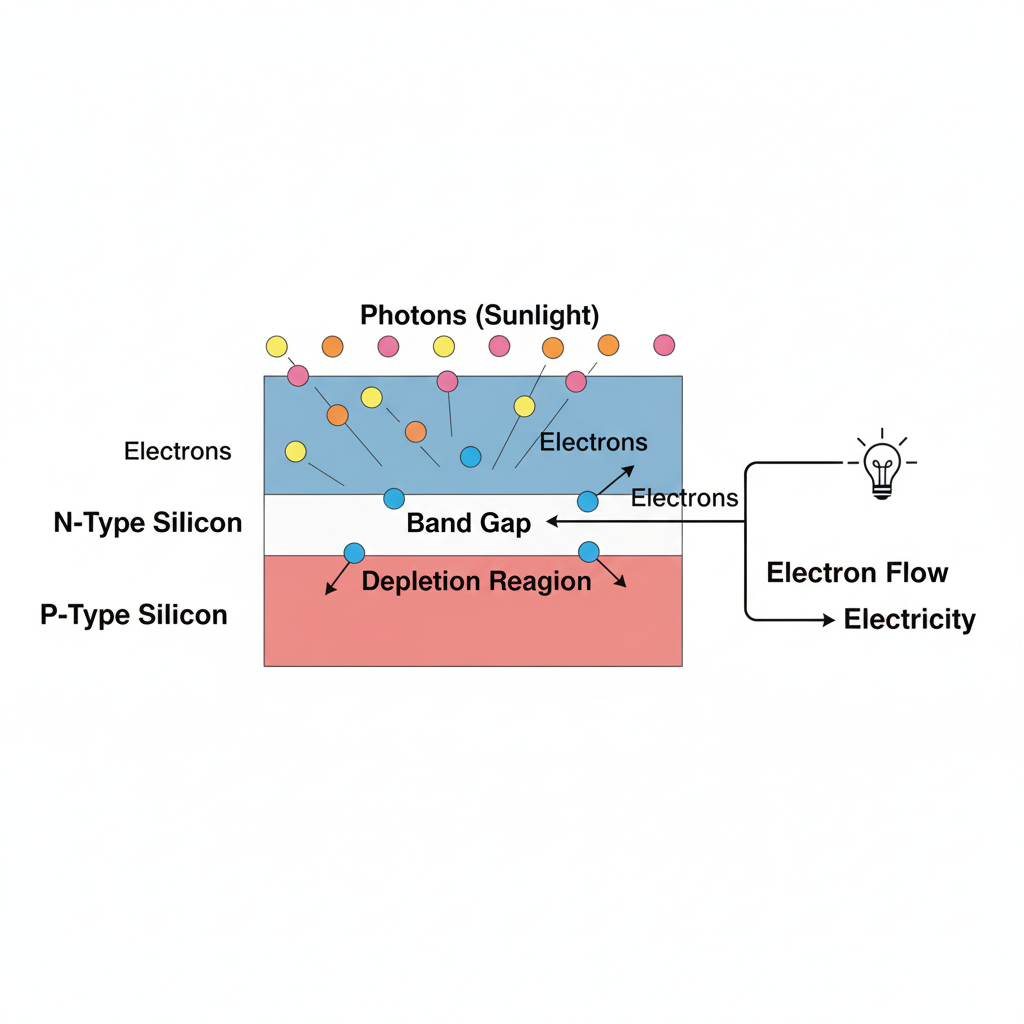

This is where we have to look at the physics of the solar panel itself. A solar panel isn't just a "light-catcher." It's a very specific electronic device that works on a quantum principle.

Principles of the Photovoltaic Effect

A solar panel is made of a semiconductor, usually silicon. In simple terms, the silicon atoms hold their electrons in a stable, orderly fashion. They're "stuck" in place.

To generate electricity (which is just the flow of electrons), you have to knock an electron loose.

This is done by photons, which are little packets of light energy. But here’s the critical rule of the photovoltaic effect: Not just any photon will do.

A photon must have a minimum amount of energy to knock the electron free. This minimum energy hurdle is called the band gap of the material.

- If a photon hits with less energy than the band gap, it does nothing. It's like throwing a ping-pong ball at a bowling pin. The electron doesn't budge. The energy just turns into a tiny bit of heat.

- If a photon hits with more energy than the band gap, it knocks the electron loose, and that electron can now flow through a circuit as electricity.

Moonlight is just reflected sunlight, so the color (and thus the energy of individual photons) is roughly the same. The problem isn't the quality of the photons; it's the quantity.

There are just so, so, so few photons arriving from the moon that the panel can't generate any meaningful current (the number of electrons flowing).

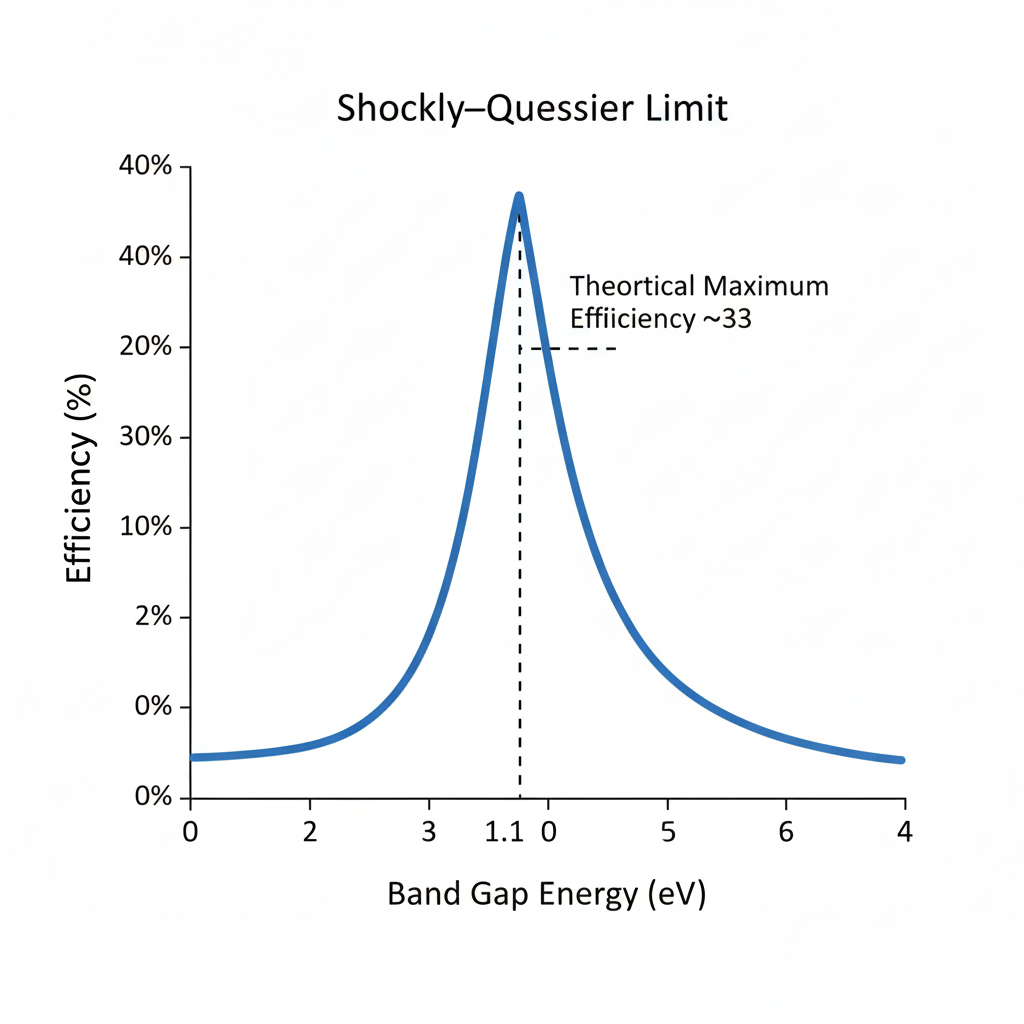

State-of-the-Art Photovoltaic Efficiency

Even in a perfect scenario, solar panels aren't 100% efficient. The theoretical maximum efficiency for a standard silicon solar panel (called the Shockley-Queisser Limit) is around 33%.

In the real world, the panels on someone's roof are typically 18% to 22% efficient. This means that of the 1,000 W/m² of sunlight hitting them, they can successfully convert about 180-220 W into usable electricity.

Calculating the Theoretical Maximum Power from Moonlight

Let's do the math on moonlight. We'll be wildly optimistic.

- Start with our energy: 0.001 W/m² (from a bright full moon).

- Use a huge solar array: Let's say you have a massive 100-square-meter array on your roof (most homes are smaller).

- Calculate total energy hitting the array: 0.001 W/m² × 100 m² = 0.1 Watts.

- Apply our panel efficiency: Let's assume a good 20% efficiency.

- 0.1 W × 0.20 = 0.02 Watts of power.

That is the absolute maximum power you could theoretically get from a massive rooftop solar array under a perfect full moon.

What can 0.02 Watts power?

A single, tiny red LED on a circuit board requires about 0.04 W to light up.

Your entire roof, covered in solar panels, could not generate enough power from a full moon to turn on a single tiny indicator light.

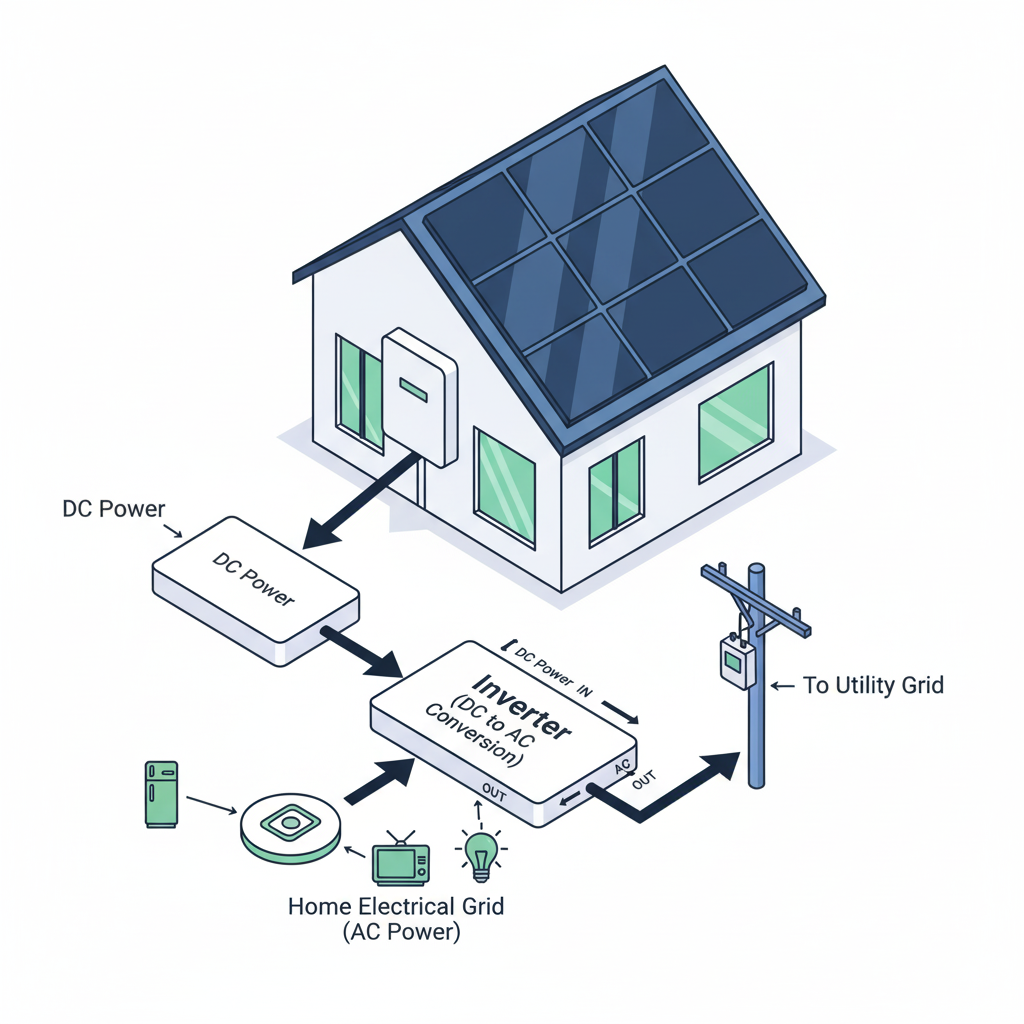

Practical Engineering Barriers: System-Level Inviability

It's actually even worse than that. A solar power system isn't just the panels. It has complex electronics, most importantly an inverter, which converts the low-voltage DC power from the panels into the high-voltage AC power your house uses.

These inverters have a "wake-up" or "startup" voltage. They need a minimum amount of power just to turn on and start their own internal computer. This is often 50 or 100 Watts.

The 0.02 Watts from the moonlight isn't just "not enough to be useful"—it is so far below the system's operating threshold that the inverter would never even register it. It's like trying to start a car engine by blowing on the fan blades. The system is, and will remain, completely asleep.

Deconstructing the "Beating Solar by 35%" Claim

So, if the science is this painfully clear... where on Earth did the "Beating Solar by 35%" myth come from?

This is a classic case of scientific misinformation. It’s so bizarre and specific that it sounds credible.

The Absence of a Viable Performance Metric

Let's first just analyze the sentence: "New panel beats solar by 35%."

Beats it at what? This claim is called "metric-less."

Does it mean it generates 35% more power than a regular solar panel? That's impossible. We just calculated the power is functionally zero.

Does it mean it's 35% efficient? An efficiency of 35% is amazing... but it's 35% of what? As we saw, 35% of 0.02 W is still 0.007 W. It's less power, not more.

The claim is mathematical nonsense. It's a string of technical-sounding words designed to confuse you, not inform you.

Investigating the Origins of a Fabricated Figure

The "35%" figure appears to be pulled from thin air. It’s a common tactic in pseudoscience. Why 35%? Why not 30% or 40%? Because 35% sounds specific. It sounds like someone ran an experiment and got a real number.

This specific, "data-like" number makes the lie feel "scientific" and encourages people to share it without question.

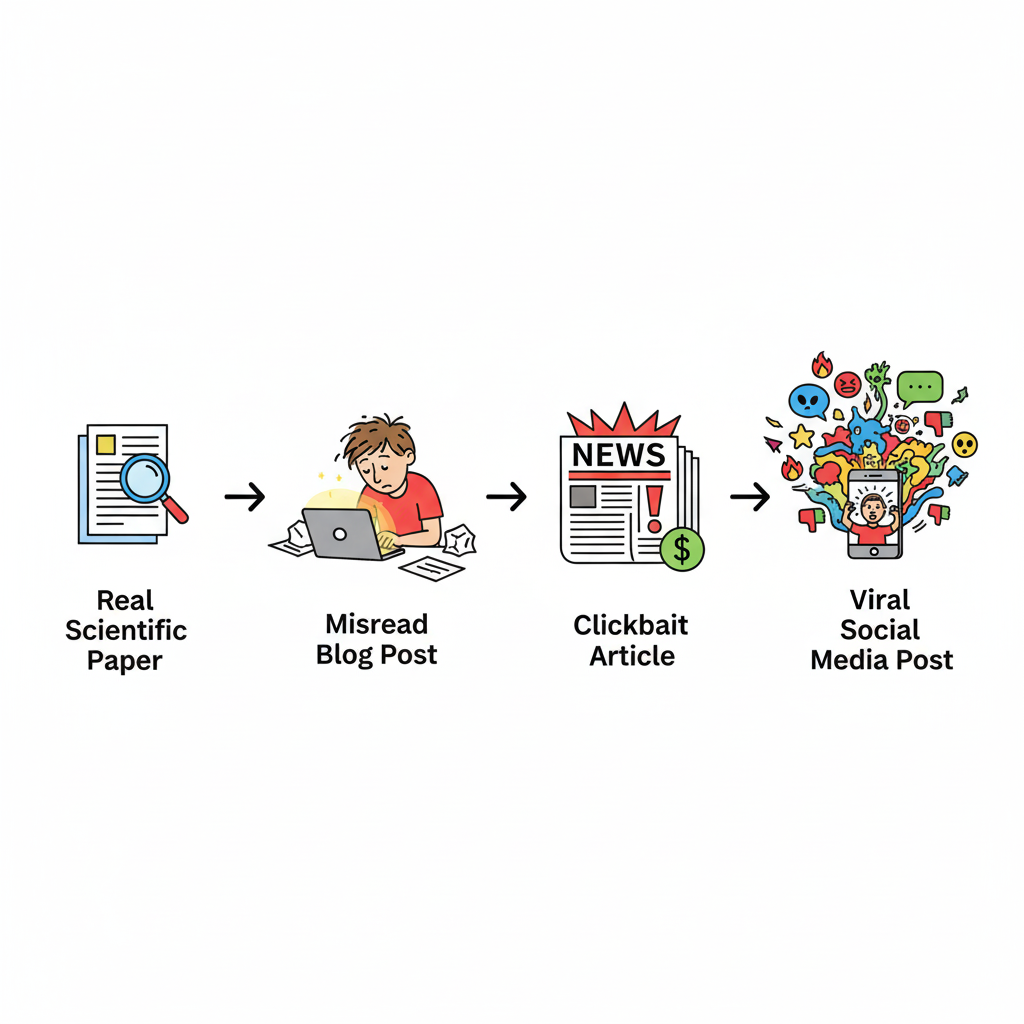

The myth of moonlight power is an old one, but it got a massive, viral boost a few years ago when it collided with a different real story. And that's where things get really interesting.

The Genesis of the Myth: Conflating Moonlight with Nighttime Radiative Cooling

Here is the twist in our detective story. In 2019, a real team of brilliant scientists did invent a panel that generates electricity at night.

The internet heard "panel makes power at night" and assumed it must be using moonlight.

This was completely wrong. The device had nothing to do with light. It used heat. Or, more accurately, it used cold.

The Phenomenon of Radiative Cooling

This is the real science, and it's incredibly cool (pun intended).

On any clear night, every object on Earth—your roof, your car, the grass—is constantly beaming its own heat (infrared radiation) out into the universe. If there are clouds, that heat gets reflected back. But on a clear night, that heat radiates away unimpeded into the -270°C (-454°F) cold of deep space.

This is why your car windshield can have frost on it in the morning even when the air temperature never dropped to freezing. The windshield radiated its heat away so fast that its own surface became colder than the surrounding air.

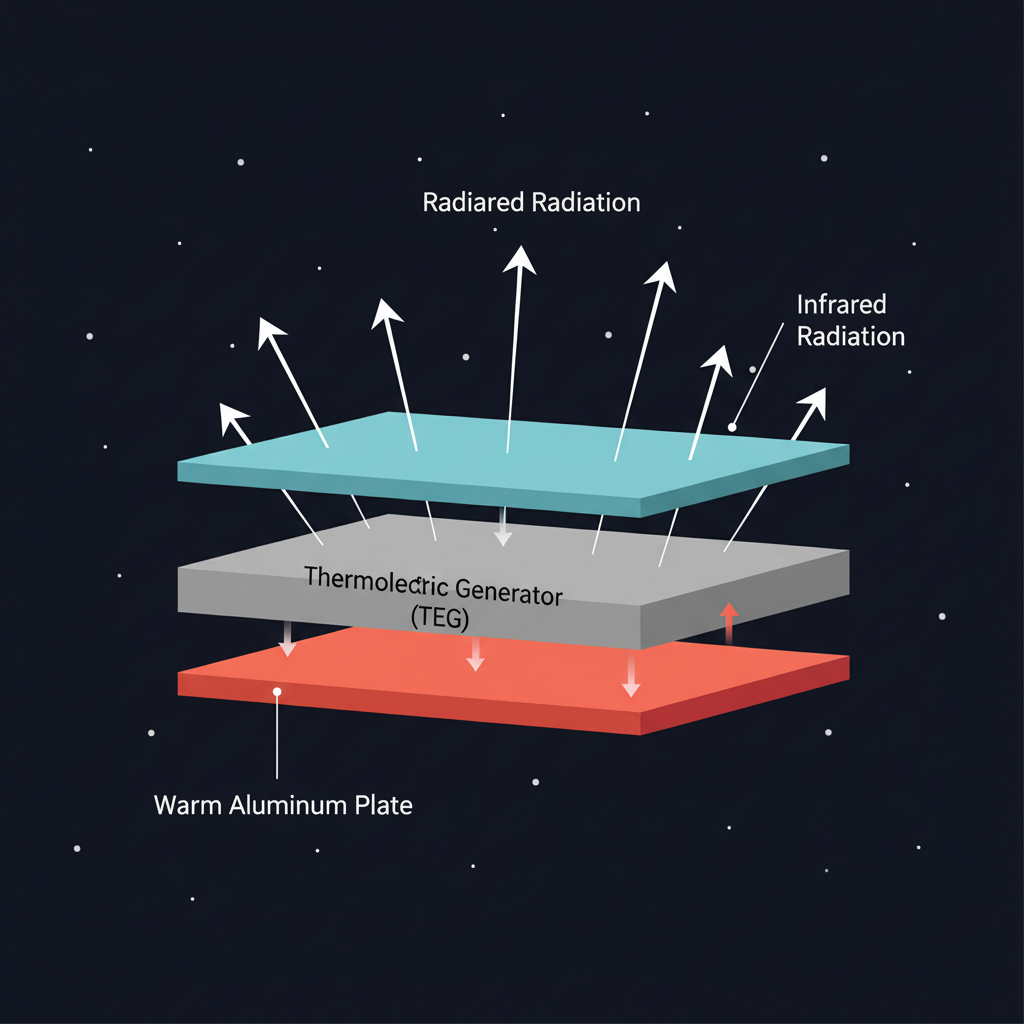

The Stanford University Innovation

A team of engineers at Stanford University (and later, other teams) asked a brilliant question: "Can we harvest energy from this temperature difference?"

They built a special device that works like a solar panel in reverse.

- The Panel: The top of the device is a surface designed to be extremely good at radiating its heat into space. It gets very, very cold—several degrees colder than the air around it.

- The Heat Source: The bottom of the device is just a simple aluminum plate that stays warm by soaking up heat from the ambient night air.

- The Engine: Sandwiched between the cold top and the warm bottom, they placed a thermoelectric generator (TEG). A TEG is a simple, solid-state device that creates a voltage (and thus electricity) when one side is hot and the other side is cold.

This device actually works. It uses the "coldness" of deep space as a resource, creating a tiny but real electrical current all night long.

A Comparative Analysis of Nighttime Power Technologies

So, how does this real nighttime technology stack up?

- Moonlight Solar Power (Theoretical): ≈ 0.00002 W/m² (using our 0.02 W / 100 m² calculation). It's effectively zero.

- Radiative Cooling TEG Power (Actual): The Stanford prototype generated about 50 milliwatts per square meter (or 0.05 W/m²).

This is still thousands of times less power than a daytime solar panel (0.05 W vs. 200 W). It is not a solution for powering a city or a home. But it's perfect for low-power applications, like keeping remote weather sensors or military monitoring devices running overnight without a battery.

And, most importantly: It is infinitely more power than moonlight.

The Anatomy of Scientific Misinformation

Now we can see exactly how the myth was born.

- THE REAL SCIENCE: "Stanford Scientists Invent a Panel That Generates Electricity at Night!" (using radiative cooling and a thermoelectric generator).

- THE MISUNDERSTANDING: A blog or social media user sees the headline. They don't read the article. They think, "A panel that works at night? The brightest thing at night is the moon. It must use moonlight!"

- THE CONFLATION: They post: "Wow, Stanford invented a moonlight solar panel!"

- THE EXAGGERATION (CLICKBAIT): A content farm steals that post and spices it up: "New Moonlight Panel is So Efficient It Could Power Your Home!"

- THE FABRICATION: To make it sound "real," someone invents a number: "This New Moonlight Panel is a Breakthrough, Beating Solar by 35%!"

And just like that, a real, modest, and clever piece of engineering (radiative cooling) is twisted into a mythical, impossible "moonlight panel."

The Broader Landscape of "Lunar" and Low-Light Energy

This whole story doesn't mean that space is useless or that low-light power is a fantasy. It just means we have to be precise and use our critical thinking skills.

Legitimate "Lunar" Energy Concepts: A Necessary Clarification

There is a very real and powerful form of "lunar energy." It just has nothing to do with light.

It's Tidal Power.

The moon's gravity is powerful enough to pull on Earth's vast oceans, creating the daily high and low tides. This movement of trillions of tons of water is a massive, kinetic energy source. Humans have built tidal power plants that use underwater turbines, like windmills, which are spun by the incoming and outgoing tides to generate gigawatts of clean, predictable electricity.

So, if you ever want to talk about "lunar energy," this is the real deal. It's the power of the moon's gravity, not its light.

The True Frontier of Low-Light Photovoltaics: Indoor Energy Harvesting

So, is there any use for a solar panel that works in low light? Absolutely. But the "low light" they're designed for isn't the moon. It's your office lamp.

The true frontier of low-light PV is indoor energy harvesting.

Scientists are developing new types of solar cells (using materials like perovskites or dye-sensitized cells) that are specifically tuned to capture the wavelengths of light produced by LEDs and fluorescent bulbs.

The goal isn't to power your house. The goal is to power the "Internet of Things" (IoT). Imagine a smart temperature sensor in every room, a small security camera, or an electronic shipping label that never needs a battery change. It just sips all the power it needs from the ambient light in the room.

This is the real, exciting future of low-light photovoltaics. It’s not about the moon; it’s about finally killing the AA battery.

A Verdict on Moonlight Power

So, let's return to our original case. Is "moonlight power" real?

The verdict is in, and it's an open-and-shut case.

Summary of Findings

- Motive: The desire for 24/7 renewable energy is strong, making us want to believe.

- Opportunity: Moonlight does exist, and solar panels exist. The "crime" seems plausible.

- The Evidence: The numbers are damning. Moonlight is 400,000 to 1,000,000 times weaker than sunlight. A massive rooftop array could not even power a single LED.

- The "How-To": The physics of a solar panel—specifically, its "startup voltage" and the quantum "band gap"—make it impossible for the system to even "wake up" using such a tiny trickle of energy.

- The Real Culprit: The myth is a case of mistaken identity. A real nighttime technology (radiative cooling) was misreported and conflated with the idea of moonlight.

Clarification of the Misunderstanding

"Moonlight power" is a fabrication. It's a textbook example of how a grain of truth can be twisted into a mountain of misinformation. The claims are physically impossible, mathematically nonsensical, and rooted in a complete misunderstanding of a different, real technology.

Recommendations for Critical Evaluation

You are now smarter than 99% of the people who see and share these "moonlight panel" articles. As an energy detective, you have a new toolkit. The next time you see a wild scientific claim, use these steps:

- Check the Numbers: Always ask "how much?" Do a "back-of-the-envelope" calculation. If the energy source (moonlight) is a million times weaker, the power output will also be a million times weaker.

- Check the Source: Did this claim come from a peer-reviewed scientific journal (like the real Stanford paper) or a random blog, YouTube video, or "weird tech" website? Always try to find the primary source.

- Check the "Mechanism": Ask how it works, in detail. "It uses the moon's special frequencies" is pseudoscience. "It uses a thermoelectric generator to harvest the temperature difference between a cold plate and the ambient air" is real science.

The universe is full of amazing energy. It's in the blazing heart of the sun, the gravitational pull of the moon, and even the cold, empty blackness of deep space. We don't need to invent fake energy sources. The real ones are fascinating enough.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: But what if we made a solar panel that was 100% efficient? Could it work on moonlight then?

A: Even with a magical 100% efficient panel, our 100-square-meter roof would only generate 0.1 W of power. This is still not enough to power anything useful, and it's certainly not enough to turn on the inverter that connects the system to your house. The source energy is the problem, not the panel's efficiency.

Q: Couldn't we just use a giant magnifying glass or a field of mirrors to concentrate the moonlight onto one panel?

A: This is a great question! In theory, yes. This is how "concentrated solar power" (CSP) works in the desert. However, to get 1,000 W/m² (sun-level power) from 0.001 W/m² (moon-level power), you would need a mirror/lens array one million times larger than your target solar panel. To get enough power for one house, you would need to build a mirror array covering many square miles. At that point, it would be astronomically cheaper and easier to just use regular solar panels during theDay and store the power in a battery.

Q: So that Stanford radiative cooling thing... could it power my house?

A: Not even close. The power output is tiny—about 0.05 W/m². A typical house at night might idle using 200-500 W (refrigerator, router, standby electronics). To get 200 W from this tech, you'd need a panel covering 4,000 m², which is about the size of a football field. Its real-world use is for tiny, remote sensors that need to "sip" power, not for residential or industrial power.

Q: Why is the moon so dim? I thought it was bright white.

A: It's an optical illusion! Our eyes are fantastic at adjusting. When you're in a dark room, even a tiny candle seems bright. The moon is floating in the blackest black imaginable (space), so our brains "turn up the brightness" to see it. If you were to see the moon in the daytime (when it's often visible) next to a white cloud, you'd see its true, dark, rocky-gray color.

Q: Is tidal (lunar gravity) power better than solar power?

A: It's not "better" or "worse," just different! Its biggest advantage is that it's 100% predictable. We know the tides years in advance. Solar power, by contrast, varies with clouds, weather, and the time of day. The main disadvantage of tidal power is that it only works in very specific coastal locations with large tidal shifts, and the high-salt, high-motion environment is very tough on the machinery. A great energy grid uses all of them: solar for the day, wind for when it's blowing, and tidal for its rock-solid predictability.