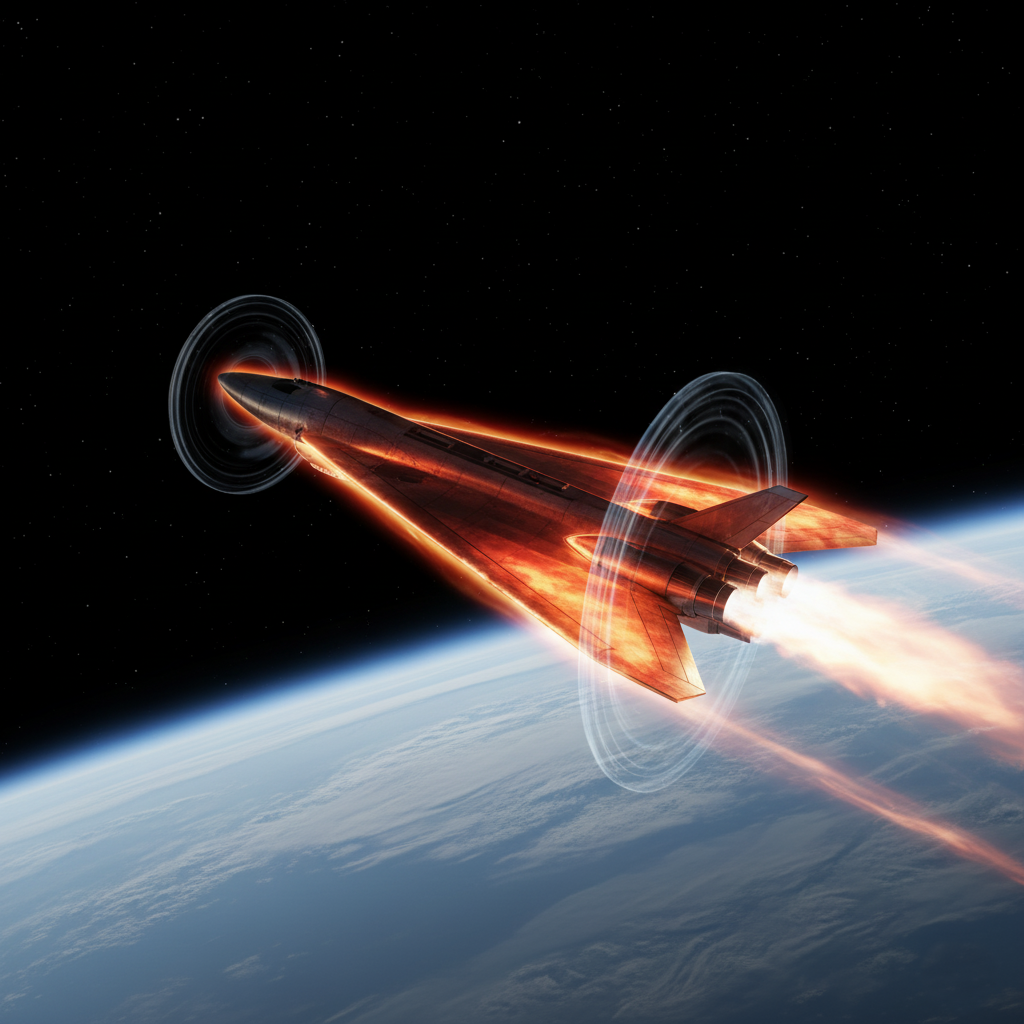

Imagine you’re in New York. You text your friend in Sydney, Australia, "Just boarding, see you soon." Then you board a sleek, futuristic aircraft. You don't just take off; you launch. Climbing to the edge of space, you cruise at speeds that blur the line between aviation and astronautics. Ninety minutes later—before your friend in Sydney has even finished their breakfast—you land. This isn’t science fiction. This is the promise of hypersonic flight, a technological revolution that is simmering on the verge of boiling over.

The word "hypersonic" itself sounds like something from a comic book. It means flying at or above Mach 5, or five times the speed of sound. That’s over 3,800 miles per hour (6,100 km/h). But the real trailblazers, companies like Australia’s Hypersonix Launch Systems, aren't just aiming for Mach 5. They’re targeting Mach 12.

That’s over 9,000 miles per hour.

But here’s the secret: getting there isn't about just building a better jet engine. It’s about taming physics. It’s about reinventing the very concept of an engine, the fuel we use, and even the materials we build with. It requires an engine that can breathe fire in a 3,00-degree inferno and a fuel that doubles as liquid-nitrogen-cold life support. This is the story of the scramjet, the hydrogen paradigm, and the incredible quest to build the "Green Comet."

The Mach 12 Claim: What Does It Really Mean?

When you hear a company claim they are building a "Mach 12 vehicle," it’s easy to picture a gleaming passenger plane ready for booking. Let's pull back the curtain on that claim. This is the "executive analysis"—breaking down what's real, what's hype, and why it all matters.

Why Mach 12 Is the Magic Number

First, why care? Why is Mach 12 so much more important than, say, Mach 4?

The motivation is simple: it changes everything. At speeds between Mach 5 and Mach 10 (high hypersonics), you can revolutionize global travel and defense. But once you push past Mach 10 and head toward Mach 12, you're not just flying fast—you're knocking on the door of space. A vehicle traveling that fast can "skip" off the atmosphere like a stone on a lake, or, with a little more push, achieve low Earth orbit.

This speed is the key to unlocking the holy grail of space travel: a reusable, single-stage-to-orbit (SSTO) spaceplane. No more giant, disposable rockets that cost hundreds of millions per launch. Imagine an "airplane" that takes off from a runway, delivers a satellite to orbit, and then flies back to land, refuel, and go again the same day. That’s the value. That's the Mach 12 dream.

Deconstructing the "Claim"

So, does this vehicle exist? No. Not yet.

When companies test these technologies, they aren't rolling a finished plane out of a hangar. They are firing an engine, bolted to a concrete test stand, for a few seconds. Or they are launching a small, uncrewed prototype (like the 10-foot-long DART AE) on top of a rocket to get it up to speed, where it will hopefully ignite, gather data, and then crash into the ocean as planned.

The "Mach 12 claim" is a design target. It’s the "North Star" for the engineers. The value in the claim isn't that it's finished; it's that a company has a credible, physics-based roadmap to get there. The execution is about proving it, piece by piece. First, prove the engine works in a wind tunnel. Next, prove it works in a short, real-world flight. Then, build a bigger one. This is a marathon, not a sprint, and we are just hearing the starting gun.

The Heart of the Beast: Inside the SPARTAN Scramjet

You can't get to Mach 12 with an engine that has moving parts. At that speed, any fan blade, turbine, or compressor from a normal jet engine would instantly melt, shatter, and be blasted out the back.

You need an engine with no moving parts. You need a scramjet.

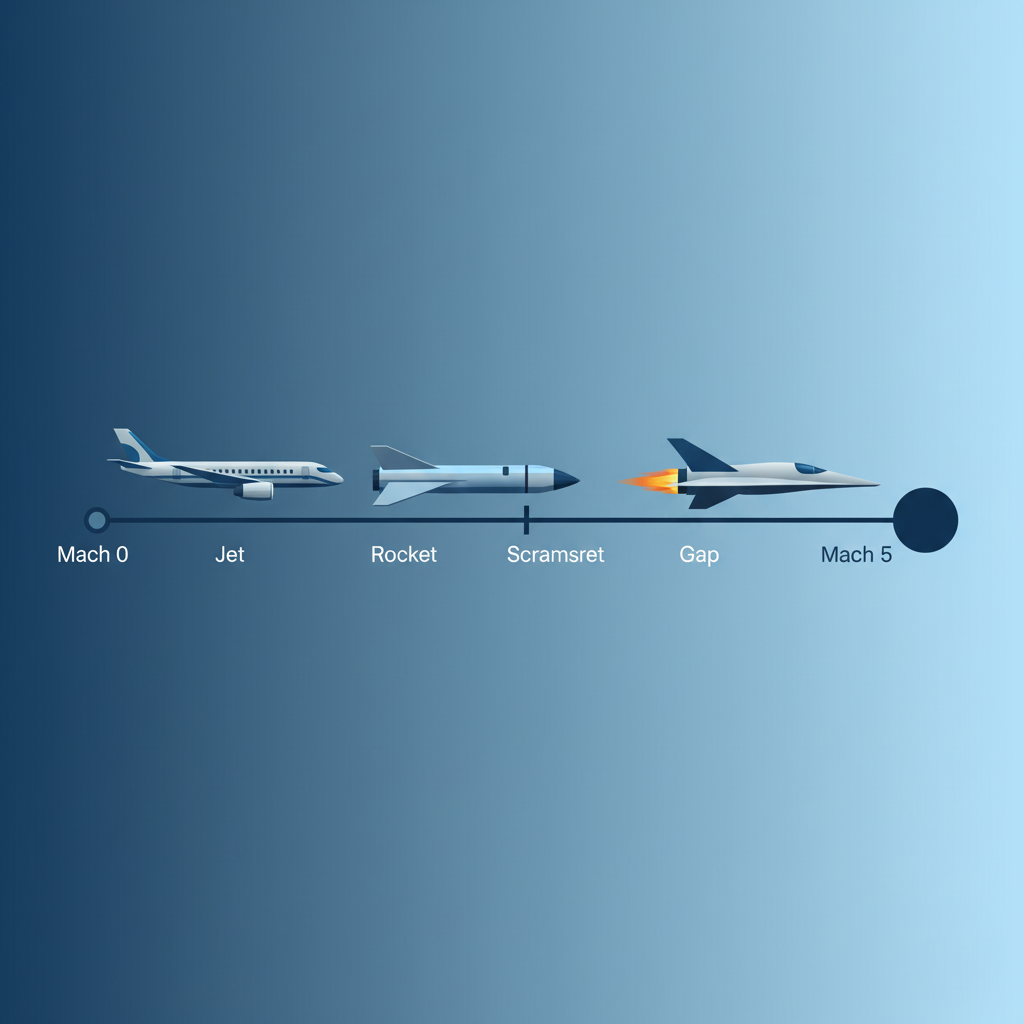

From Jet Engine to Scramjet

Let's connect the dots.

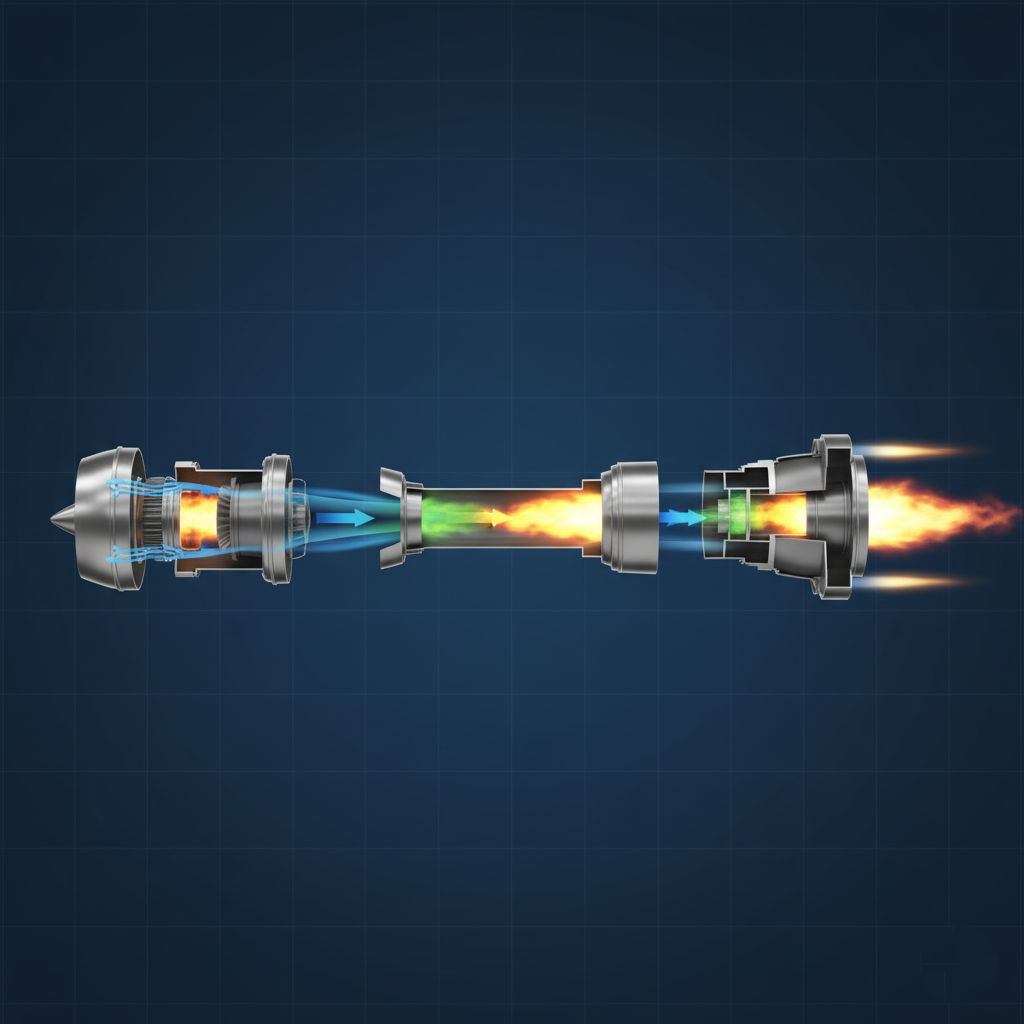

- A normal jet engine (like on a 747) uses giant fans in the front to suck in air, squeeze it (compress), bang (ignite it with fuel), and blow (shoot it out the back). This works up to about Mach 2.

- A ramjet is simpler. It’s for supersonic flight (Mach 2-4). It's basically a hollow tube that uses its own incredible speed to "ram" air into the engine, compressing it without any fans.

- A scramjet (or Supersonic Combustion RAMJET) is the final evolution. It’s a ramjet that is so fast (Mach 5+), the air never slows down to subsonic speeds. The combustion—the "bang"—happens in a supersonic airflow.

This is where you get the most famous analogy in engineering: lighting a scramjet is like trying to light a match and keep it lit in the middle of a Category 5 hurricane.

The SPARTAN Difference

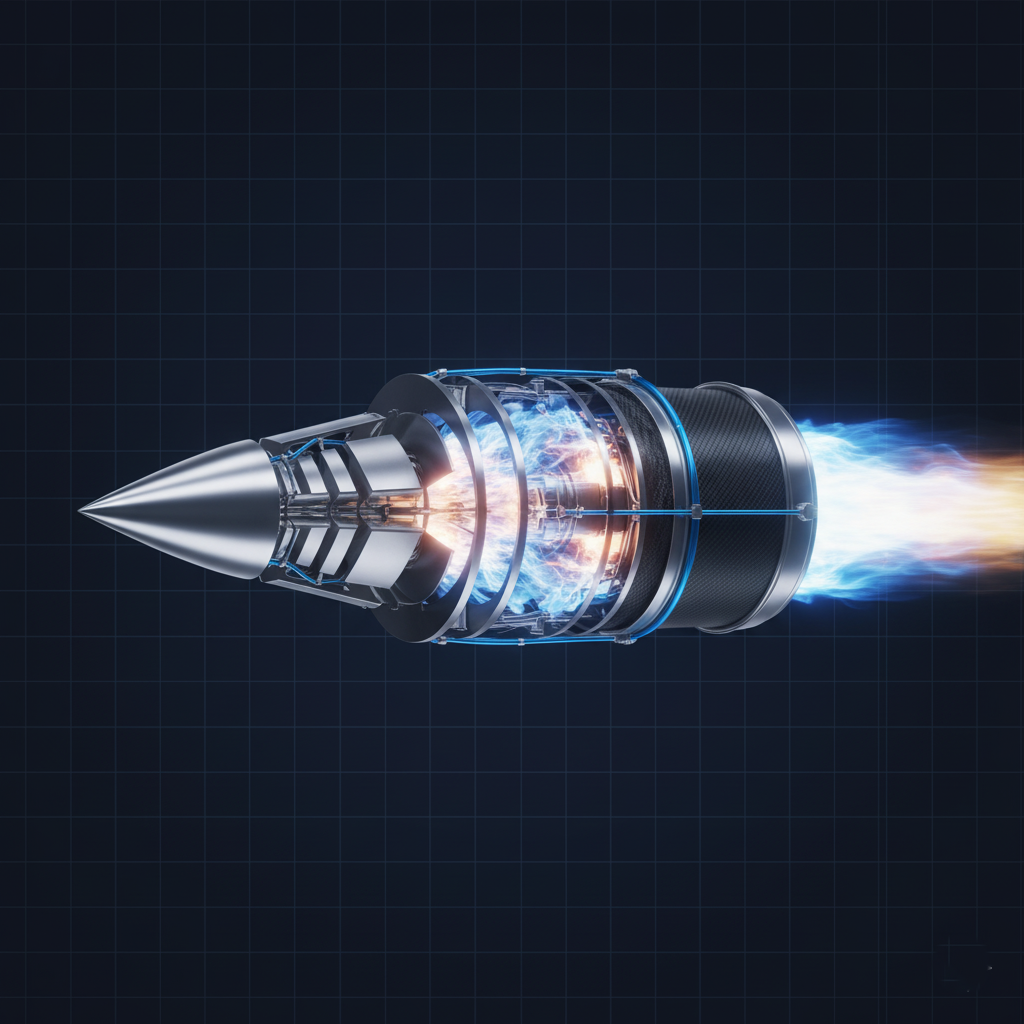

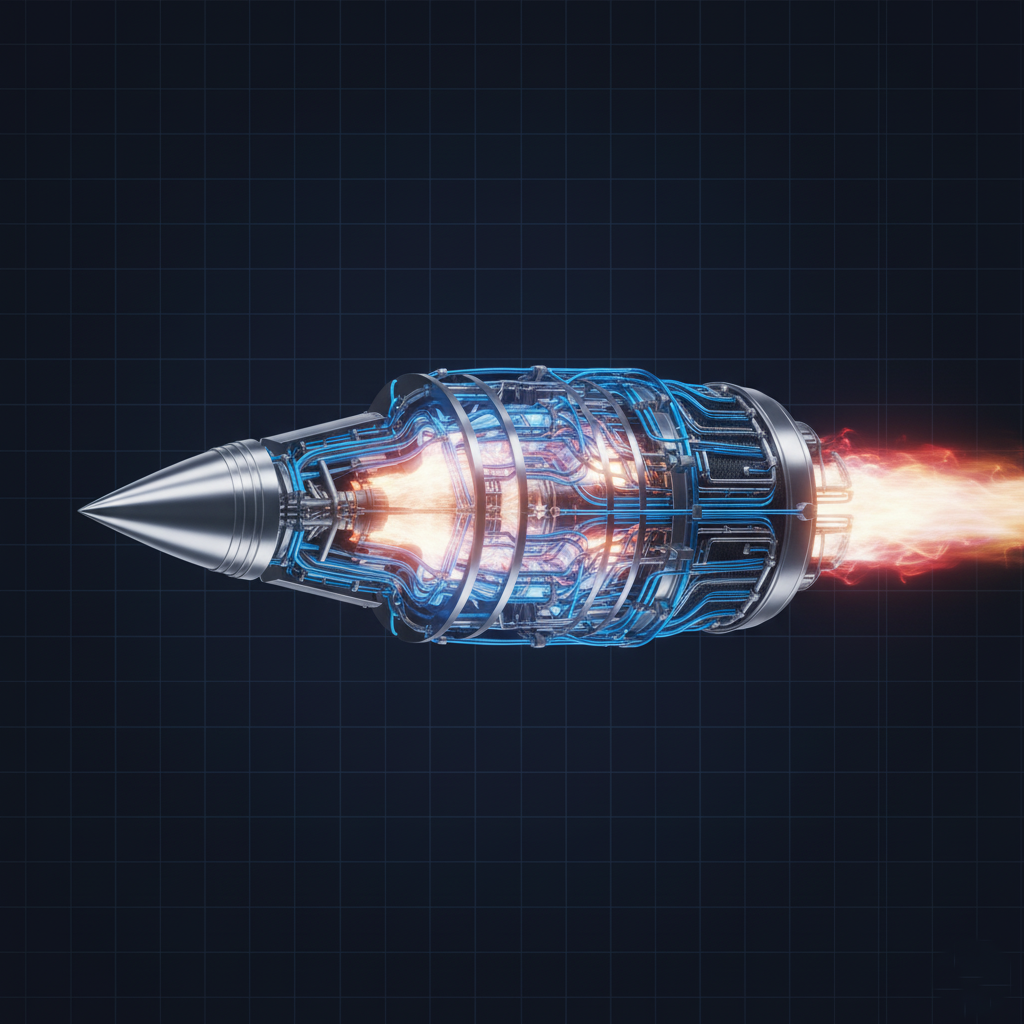

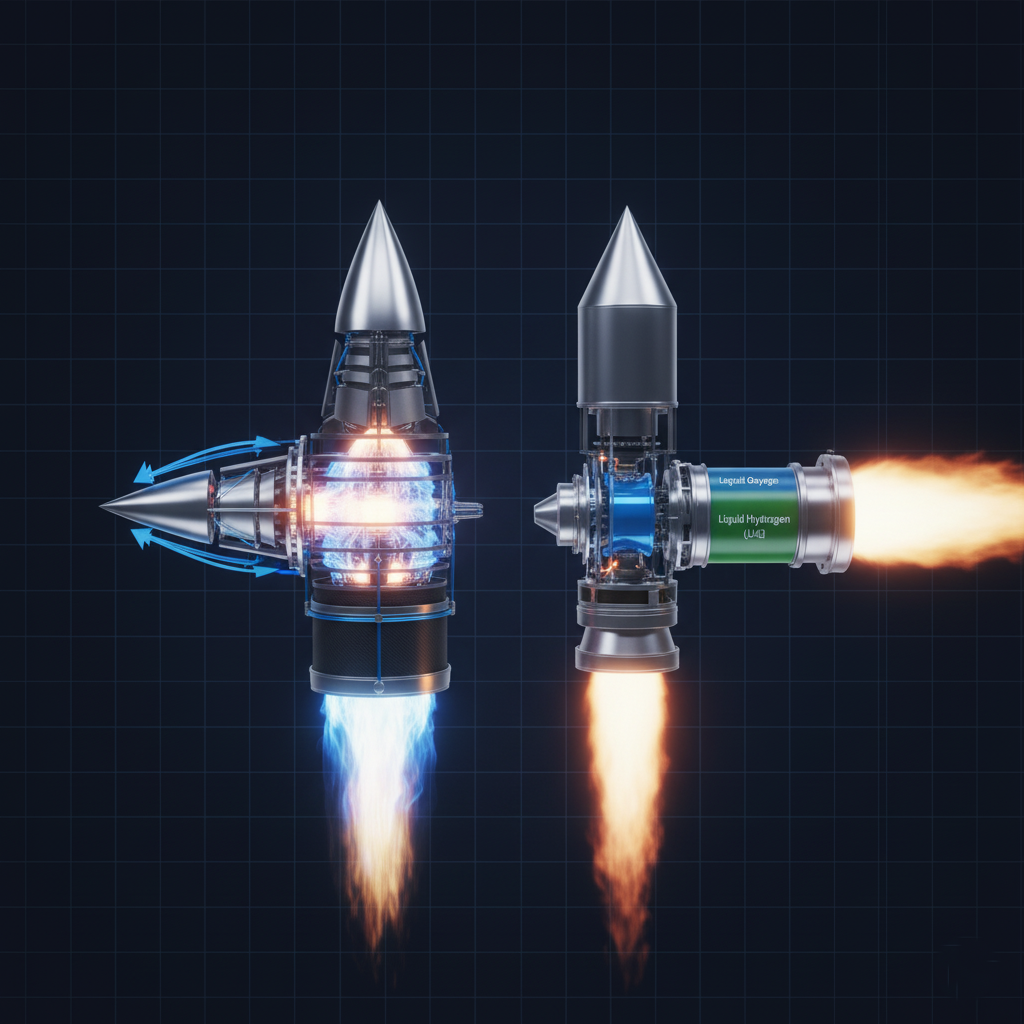

The SPARTAN engine, developed by Hypersonix, is a masterclass in this technology. Its value lies in its design. It's built to be reusable, reliable, and relatively cheap. How? The execution is a blend of physics and revolutionary manufacturing.

The engine itself is a meticulously shaped tube. The front inlet is designed to grab the supersonic air and, using a series of shockwaves, guide it into the combustion chamber. At that exact moment, hydrogen fuel is injected, and... whoosh. The trick is to have the flame ignite and stay in one place (a process called "flame-holding") without being blown out the back, all in less than a thousandth of a second.

The SPARTAN is designed to be 3D-printed from high-temperature alloys. This isn't just a gimmick. As we'll see, 3D printing is the only way to build the complex internal structures needed to keep it from melting.

The Green Fire: Why Hydrogen Is the Only Answer

Here is the single biggest problem with hypersonic flight: heat.

At Mach 5, the friction with the air heats the "skin" of an aircraft to over 1,000°C (1,800°F). At Mach 12, you're looking at temperatures that can exceed 3,000°C, hotter than the inside of a blast furnace. Aluminum melts. Steel melts. Titanium glows white-hot and loses its strength. The air itself stops being "air" and becomes a superheated, electrically charged plasma.

You can't just block this heat. You have to use it.

Fuel That Pulls Double Duty

This is where the hydrogen fuel paradigm becomes so brilliant. The value of hydrogen isn't just that it's a powerful fuel; it's that it is also an incredible coolant.

Liquid hydrogen is stored at a cryogenic -253°C (-423°F). It's one of the coldest substances we can create. The execution of a hydrogen-powered scramjet is a work of genius called regenerative cooling.

- Before the liquid hydrogen is ever injected into the engine to be burned, it's first pumped through a network of tiny, hair-thin pipes and channels.

- These pipes are built directly into the walls of the engine and the "leading edges" of the wings—the parts that face the plasma blowtorch.

- As the -253°C hydrogen flows through these walls, it absorbs the heat. It sucks the thermal energy out of the metal, keeping the engine from vaporizing.

- This is the brilliant part: all that absorbed heat energy doesn't just disappear. It "pre-heats" the hydrogen, turning it from a frigid liquid into a high-pressure, high-energy gas.

- This super-energized gas is then injected into the combustion chamber, where it explodes with even more power.

The fuel cools the engine, and in doing so, the engine pre-heats the fuel. It's a perfect, self-sustaining loop.

The "Green" Comet

And the connection? The "green" part of the "Green Comet" title isn't just about the color of a plasma shockwave. The only exhaust product from burning hydrogen (H) with air (which contains oxygen, O) is H₂O.

Water.

In a world desperate for sustainable solutions, this technology offers a future of high-speed global transport and space access that is carbon-neutral.

A Fleet for the Future: The Hypersonic Vehicle Portfolio

This technology isn't being developed for just one "super plane." The goal is to create a whole portfolio of vehicles for different applications, scaling the technology up.

- Motivation: You have to walk before you can run. The motivation for a portfolio is to prove the technology at a small, cheaper scale first, then use that data to build bigger, more complex vehicles.

- Value: This "step-by-step" approach builds confidence for investors and customers.

- Execution: Hypersonix, for example, has a clear pipeline:

DART AE: A small, 3-meter-long, 3D-printed scramjet vehicle. It’s the "proof of concept." It’s designed to be launched from a rocket, hit its target speed (around Mach 7), and prove the SPARTAN engine works in the real atmosphere.

VISR: A larger, "fly-back" vehicle. This could be used for ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance). Imagine a drone that can map a crisis area or monitor weather from the edge of space, moving so fast it's virtually untouchable.

DELTA-VELOS: This is the big one. A reusable spaceplane designed to take off from a conventional runway (strapped to a reusable rocket booster), fly to the upper atmosphere at hypersonic speeds, and then launch a small satellite (up to 50kg) into low Earth orbit before flying back to land.

The commercial application for launching satellites is the most immediate and profitable goal. The world has an insatiable hunger for small satellites—for internet (like Starlink), for GPS, for Earth observation. A reusable spaceplane that can do this "on-demand" for a fraction of the cost of a 20-story rocket would completely disrupt the $400 billion space industry.

Forging the Unforgeable: The Tech That Makes It Possible

You can't build a Mach 12 engine out of the same stuff you use to build a car. The enabling technologies—the "stuff" and the "way you make the stuff"—are just as revolutionary as the engine itself.

Materials Born in Fire

The entire vehicle is a thermal management problem. The solution is a new class of materials called Ceramic Matrix Composites (CMCs).

- Connection: Think of carbon fiber, which is super strong and light. Now, imagine a material with that same strength but that also has the heat resistance of a ceramic tile on the Space Shuttle.

- Value: CMCs can withstand temperatures of 1,500°C or more without losing their shape or strength. They are used in the "hot sections" of the engine, the nose cone, and the leading edges of the wings. For other parts, engineers use "superalloys" with names like Inconel, which are designed to stay strong even when red-hot.

!(/images/materials/cmc-ceramic-matrix-composite.png)

Building with Lasers: Additive Manufacturing

Here’s the problem: How do you build an engine part that has thousands of tiny, swirling cooling channels inside its solid metal walls?

You can't. It's impossible with traditional manufacturing (casting or milling).

- Execution: The answer is 3D Printing, or what engineers call Additive Manufacturing (AM).

- Value: AM doesn't cut material away; it builds an object layer by layer from a powder. A high-powered laser melts the metal or ceramic powder one tiny dot at a time, following a 3D computer model. This allows engineers to design impossible parts. They can create internal channels that swirl and branch like the capillaries in your body, maximizing the surface area for the hydrogen coolant to absorb heat.

- Motivation: Without 3D printing, you cannot build a regeneratively-cooled scramjet. Period. This manufacturing technology is the key that unlocks the entire design. It makes the SPARTAN engine not just possible, but practical to produce.

The New Global Race: Who Else Is Building the Future?

This quest isn't happening in a vacuum. It’s a full-blown global race, with startups, aerospace giants, and superpowers all vying for hypersonic supremacy.

Commercial Ecosystem: You have a new wave of agile, ambitious startups.

- Hermeus (USA): This Atlanta-based company has a different approach. They are building a Turbine-Based Combined Cycle (TBCC) engine. It combines a regular jet engine (for takeoff to Mach 3) with a ramjet (for Mach 3 to Mach 5+). Their first goal is a Mach 5 business jet.

- Reaction Engines (UK): This team is building one of the most exciting pieces of tech on Earth: the SABRE engine. Its secret is a "pre-cooler" that can chill 1,000°C air to -150°C in 1/20th of a second, allowing its jet engine to run at much higher speeds before the scramjet-like part takes over.

Strategic (Defense) Landscape:

- The "Big 3"—the United States, China, and Russia—are pouring billions into hypersonic weapons. These are "boost-glide" missiles that are launched on a rocket and then "glide" at Mach 5+, able to maneuver unpredictably.

This is why companies like Hypersonix (partnered with the US Department of Defense) and Hermeus (partnered with the US Air Force) are receiving so much attention and funding. The same core scramjet technology that can launch a satellite can also power a defensive interceptor or a next-generation reconnaissance drone.

Comparative Analysis:

- Hypersonix (SPARTAN): Pure scramjet, hydrogen-fueled, 3D-printed, "green" focus. Aiming for full reusability and satellite launch.

- Hermeus (Chimera): Combined-cycle, jet-fuel-based, "easier" first step. Aiming for Mach 5 passenger/military flight.

- Reaction Engines (SABRE): Exotic pre-cooler, combined-cycle. Aiming for a true single-stage-to-orbit spaceplane.

Each is a different bet on how to solve the same problem. The competition is fierce, and it's pushing the technology forward at a breathtaking pace.

The Mountain We Still Have to Climb: Hypersonic Hurdles

If this all sounds amazing, you should also know that it is monstrously difficult. For every success, there are a dozen spectacular, fireball-filled failures. These are the fundamental challenges that keep engineers up at night.

The "Propulsion Gap": A scramjet is useless at a standstill. In fact, it doesn't even "turn on" until it's already flying at around Mach 5. This is the single biggest problem. How do you get the plane from 0 to Mach 5 just so the main engine can ignite?

- Execution: You need a second engine. This is the "combined cycle" problem. Do you strap it to a rocket (like DART)? Do you build a hybrid jet/ramjet (like Hermeus)? Or do you invent something new (like SABRE)? There is no easy answer.

The Inferno (Thermal Management): We talked about regenerative cooling, but it's a knife-edge. If anything goes wrong—a tiny clog in a fuel line, a crack in a ceramic tile—the plasma will win. The vehicle will melt.

Controlling the Chaos: Flying at Mach 12 isn't like flying a plane. It's like balancing a pin on the head of a needle during an earthquake. The air you're flying through isn't air; it's a chaotic, burning plasma. The vehicle is constantly being hit by shockwaves. The "control surfaces" (like ailerons) can't just be mechanical; they have to use tiny jets of gas to steer the vehicle.

Testing It on Earth: How do you test a Mach 12 engine without flying it? You need a hypersonic wind tunnel. These are not simple tunnels. They are massive, billion-dollar facilities that basically detonate a massive explosion to generate a blast of air that lasts for just a few milliseconds. These facilities are incredibly rare, meaning "test time" is a huge bottleneck for the entire industry.

The Final Verdict: From Science Fiction to Skyline

So, what’s the final takeaway from this deep dive?

The quest for Mach 12 is real. It is happening now. The claim is not a finished product, but a destination.

The synthesis of these technologies is what makes this moment in history so different. It’s the perfect storm of four key elements:

- The Engine (SPARTAN): A mature, reusable scramjet design.

- The Fuel (Hydrogen): A powerful, green fuel that also solves the cooling problem.

- The Manufacturing (3D Printing): The ability to build the "impossible" shapes the engine requires.

- The Mindset (Commercial): A shift from slow, government-only projects to fast, agile startups focused on a real market (satellites).

The "Green Comet" is an apt name. It’s fast, it’s fiery, and its tail is made of pure water.

We are at the "Wright Brothers" moment of the 21st century. The first flights will be short, terrifying, and data-rich. They will fail, often. But they will learn. Don't book your 90-minute flight to Sydney just yet. The first revolution will be in space, as satellite launches become as common as airline flights. The second revolution will be in defense.

The third, decades from now, will be you. Stepping onto a plane, buckling in, and asking the world's new favorite question: "Where should we go for lunch? I hear Paris is nice this time of year."

Frequently Asked Questions About the Hypersonic Age

What’s the difference between hypersonic and supersonic?

Supersonic is anything faster than the speed of sound (Mach 1). This is where the "sonic boom" happens. The Concorde jet was supersonic (Mach 2). Hypersonic is a huge leap, defined as speeds of Mach 5 or higher. At this speed, the physics change completely: the air friction becomes so intense it turns the air into plasma, and new engines like scramjets are required.

How is a scramjet different from a rocket?

A rocket is a "closed" system. It carries both its fuel and its oxidizer (like liquid oxygen) with it. This is why a rocket works in the vacuum of space. A scramjet is an "air-breathing" engine. It carries only its fuel (like hydrogen) and sucks the oxidizer (oxygen) it needs from the atmosphere as it flies. This makes it dramatically lighter and more efficient, but it also means it only works inside the atmosphere.

Why can't we just use regular jet engines to go that fast?

A jet engine has internal rotating parts, like compressor fans and turbines. At speeds above Mach 3, the air entering the engine is so hot that it would melt these intricate, high-precision blades. A scramjet, by having no moving parts, is designed to survive and use that intense heat and pressure.

Is hypersonic flight safe for passengers?

It absolutely could be, but safety is one of the biggest challenges. The G-forces during acceleration would need to be managed, but the real hurdle is the heat. The vehicle's thermal protection and life-support systems would have to be 100% reliable. We would need decades of data from uncrewed cargo and military flights before passengers would ever be allowed on board.

Will I ever get to fly on a hypersonic plane?

Almost certainly, but probably not soon. The first applications will be launching satellites and defense. The next step would likely be ultra-fast package delivery. Passenger travel is the final, most complex, and most expensive goal. Most experts believe it's 30-40 years away, but this technology is accelerating so quickly that the future may arrive faster than we think.