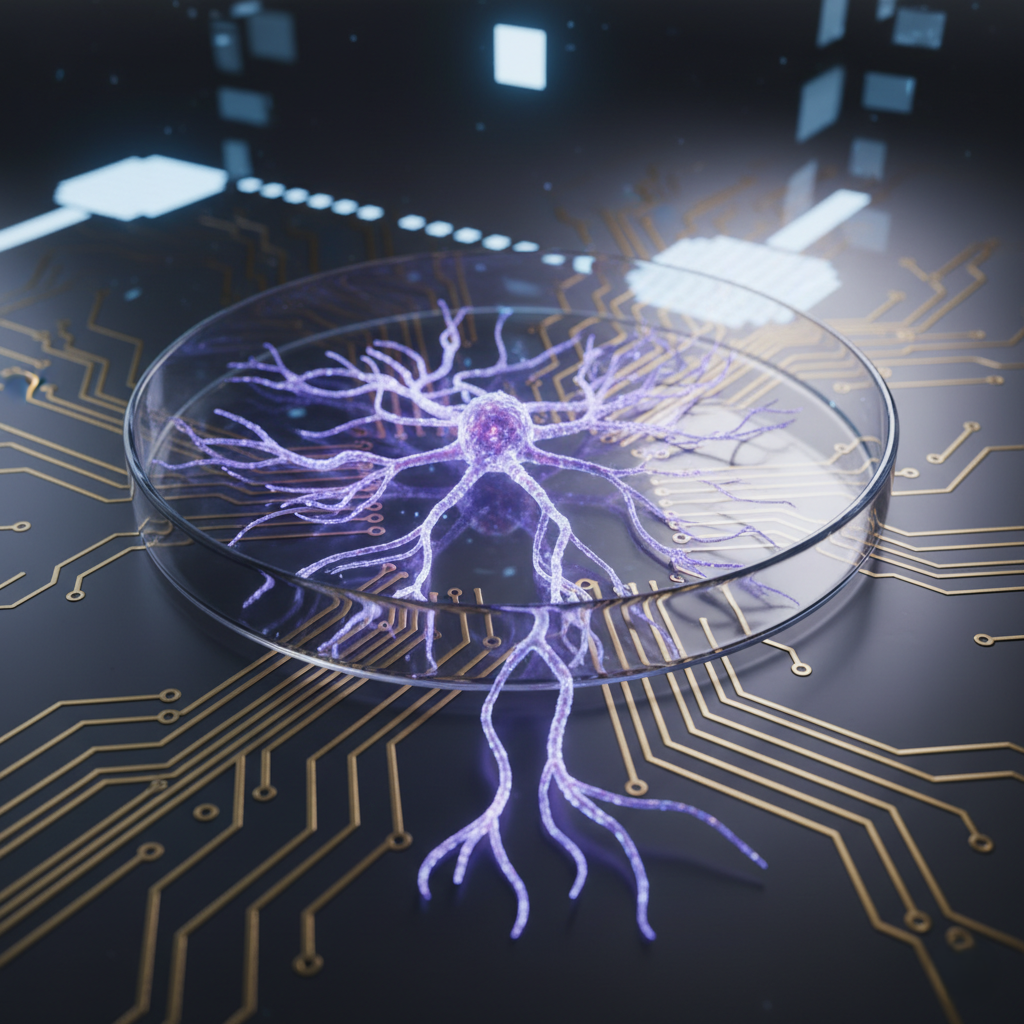

Imagine a world where your computer isn’t just made of silicon chips and cold metal, but actual living, thinking biological cells. It sounds like the plot of a science fiction movie, doesn't it? But in a groundbreaking experiment that stunned the scientific community, researchers turned this sci-fi concept into reality. They took living brain cells, placed them in a petri dish, hooked them up to a computer, and taught them to play the classic 1970s video game, Pong.

This wasn't just a neat party trick. It was a fundamental shift in how we understand intelligence, learning, and the future of technology. Known as the "DishBrain" experiment, this project has opened doors to a new frontier where biology and machines merge. Why should you care? Because this technology could one day lead to super-computers that use a fraction of the energy current ones do, or revolutionize how we test medicines for brain diseases.

Welcome to the strange, fascinating world of synthetic biological intelligence.

The DishBrain Experiment: A Revolutionary Idea

The story begins with a simple, yet profoundly difficult question: Can we interact with neurons (brain cells) directly and teach them to perform a goal-oriented task?

For years, scientists have been able to grow brain cells in labs. These cultures, often called "brain organoids" or mini-brains, would spark with electrical activity. They were alive, and they were firing, but they were disconnected from the world. They had no eyes to see, no ears to hear, and no hands to touch. They were just firing blindly in the dark.

!(/images/science/brain-organoids-lab.png)

A team at Cortical Labs in Australia decided to change that. They wanted to give these lonely cells a job. Their research, published in the prestigious journal Neuron, detailed how they took roughly 800,000 neurons—some from mouse embryos and some derived from human stem cells—and plated them onto a specialized computer chip.

This wasn't about creating a monster; it was about understanding the very roots of intelligence. By watching how these cells learned a game, researchers hoped to unlock the secrets of how our own brains pick up new skills so quickly.

System Architecture: How to Plug a Neuron into a PC

Merging wet biological matter with dry electronics is incredibly tricky. You can't just plug a USB cable into a glob of cells. The researchers needed a specialized interface, something that could act as a translator between the two very different worlds.

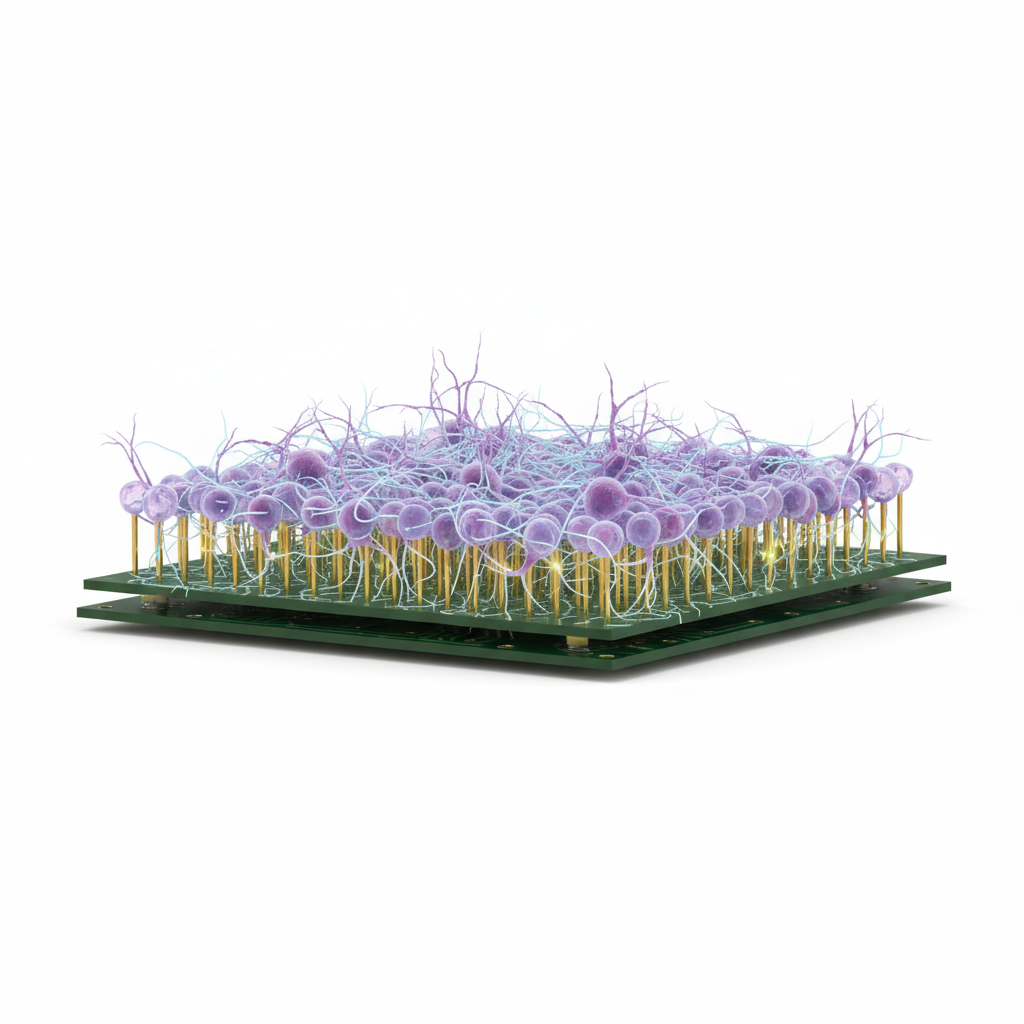

The High-Density Microelectrode Array (HD-MEA)

The secret weapon of the DishBrain experiment was a piece of hardware called a High-Density Microelectrode Array (HD-MEA). Imagine a bed of tiny nails, but microscopic. These "nails" are electrodes that can do two things:

- Read: They can listen to the tiny electrical pulses (action potentials) that neurons use to communicate.

- Write: They can send small electrical pulses into the neurons to stimulate them.

The neurons were grown directly on top of this array. As they grew, they naturally formed a dense web of connections with each other, just like they would in a real brain. The HD-MEA acted as the bridge. When the computer wanted to "talk" to the cells, it sent electrical signals through specific electrodes. When the cells "talked back," the electrodes picked up their firing patterns.

This architecture transformed the petri dish from a simple container into a highly sophisticated input/output device. It was biological hardware plugged into a silicon software system.

Embodiment: The Matrix for Microscopic Cells

Having the hardware connection was only step one. If you just randomly zap neurons, they won't learn anything. They need context. They need to feel like they are "in" a world. This concept is called embodiment.

For us, embodiment is our physical body. We know we are in a room because our eyes see walls and our skin feels the air. For DishBrain, the researchers had to create a virtual body. They chose the video game Pong because of its simplicity.

The Pong Interface

In Pong, you have a paddle that moves up and down to deflect a ball. The researchers divided the electrode array into different regions to represent this world:

- Sensory Area: Electrodes on one side of the dish would fire to tell the neurons where the ball was. If the ball was high, the top electrodes fired. If it was low, the bottom ones fired. The closer the ball got to the paddle, the faster the electrodes would fire.

- Motor Area: Two specific regions of the dish were designated as the "controls." If neurons in Region A fired, the paddle moved up. If neurons in Region B fired, the paddle moved down.

Suddenly, these cells weren't just floating in darkness. They were receiving structured information about a "ball" moving toward them, and they had a way to affect that ball by firing their own signals to move the "paddle." They were embodied in the game.

The Mechanism of Learning: Why Did They Even Try?

This is the most mind-bending part of the experiment. Why would a bunch of cells in a dish care about playing Pong? They don't get rewards like cheese or money. They don't fear "losing" the game in a traditional sense.

The answer lies in a theory called the Free Energy Principle and a concept known as Active Inference.

Preferring Order over Chaos

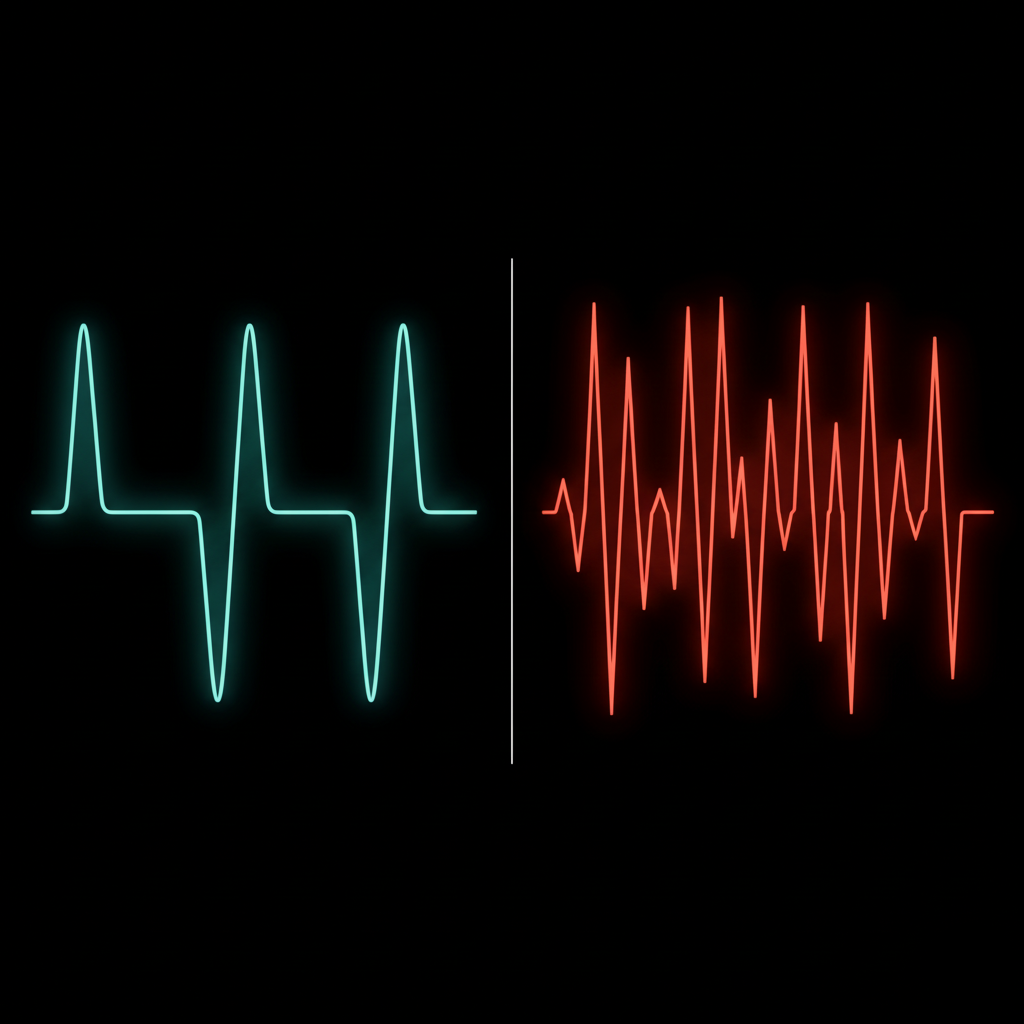

In very simple terms, biological brain cells hate unpredictability. They want their world to make sense. When things are random and chaotic, it's essentially "stressful" for neurons at a cellular level. They prefer predictable, structured inputs.

The researchers used this preference to rig the game:

- When they missed the ball: The computer sent chaotic, unpredictable, random electrical noise into the dish. The neurons hated this. It was sensory gibberish.

- When they hit the ball: The computer sent a nice, predictable, structured electrical pulse. The neurons liked this. It was orderly.

To stop the chaotic noise, the neurons had to learn how to hit the ball. They weren't "trying to win" in the way a human competes. They were just trying to make the world predictable. They learned that if they fired in a certain pattern when they received "ball location" signals, the chaotic noise would stop.

It’s like trying to tune a radio. You keep turning the dial until the annoying static goes away and you hear a clear song. The neurons were "turning the dial" of their own firing patterns until they found the clear signal that came from hitting the ball.

Performance and Key Findings: Did It Actually Work?

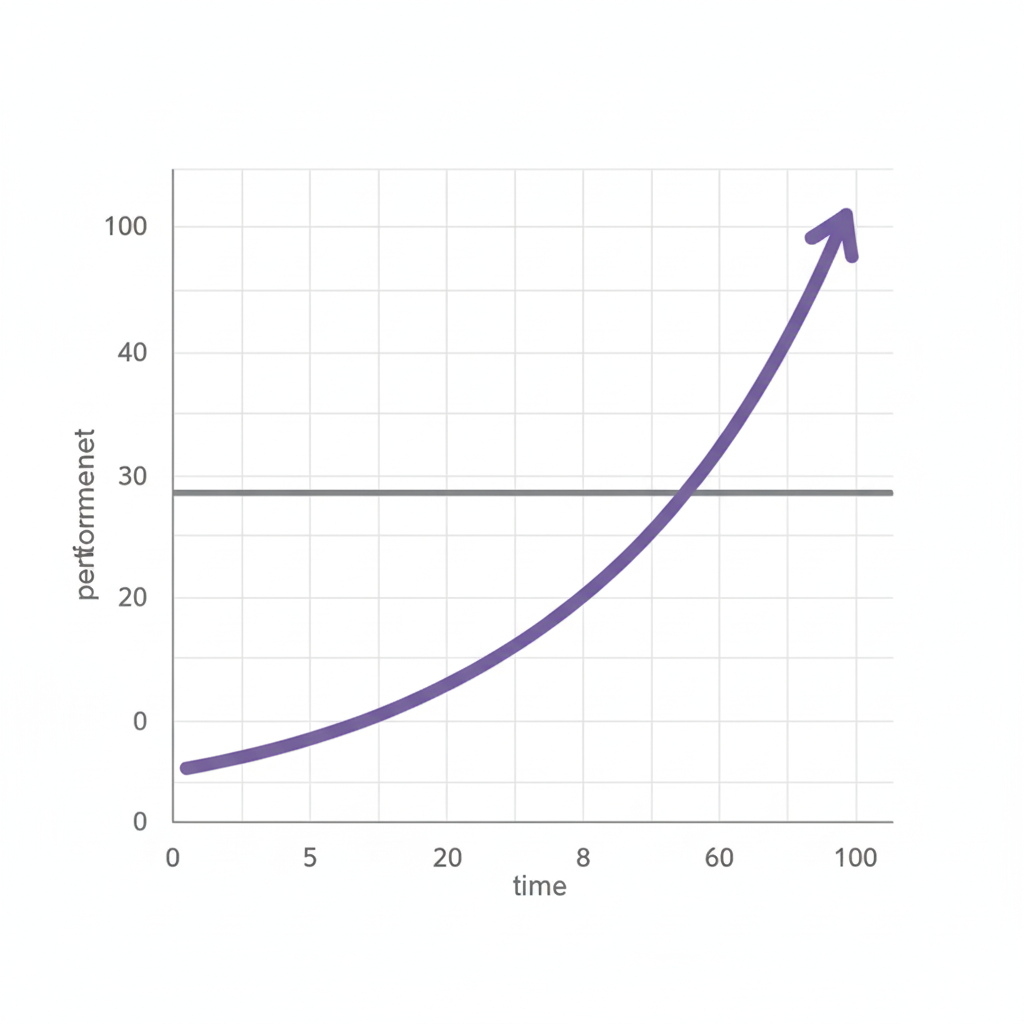

Amazingly, yes. Not only did it work, but it worked frighteningly fast.

Within just five minutes of being plugged into the simulation, the DishBrain began to show signs of learning. After about 20 minutes, it had statistically improved its gameplay. While it never reached the skill level of a human player—it missed the ball a lot—it was significantly better than random chance. It was undeniably playing.

Key Findings:

- Speed of Learning: Synthetic AI (like sophisticated machine learning algorithms) often takes huge amounts of data and time to learn a new task from scratch. The biological neurons learned the basics of Pong much faster than many traditional reinforcement learning algorithms.

- Adaptability: The cells showed a remarkable ability to adapt to a changing environment effectively instantly, something silicon-based AI still struggles with.

- Sentience vs. Consciousness: The researchers were careful with their words. They didn't claim the dish was "conscious" (self-aware). But they did argue it showed "sentience"—defined as being responsive to sensory impressions. It could sense its digital world and act upon it.

Significance, Future Applications, and Ethical Considerations

Why go through all this trouble when we have powerful digital computers? The motivation lies in efficiency and capability.

The Power of Biological Computing

Your brain uses roughly 20 watts of power—about enough to run a dim light bulb. Yet, it can do complex tasks that supercomputers requiring megawatts of electricity (and massive cooling systems) struggle with. Biological computing is incredibly energy-efficient. If we can harness this, we could build powerful processors that require barely any power.

A New Way to Test Drugs

Currently, if we want to test a new drug for Alzheimer's or epilepsy, we test it on animals or static cell cultures. Neither is perfect. Animals aren't humans, and static cells don't reflect a working brain.

DishBrain offers a third option. Imagine creating a "DishBrain" using cells derived from a patient with epilepsy. You could let it play Pong, see how the disease affects its performance, and then test drugs to see which one restores its ability to play the game. It’s functional testing on real human tissue without risking a human life.

The Ethical Frontier

Of course, this research brings up uncomfortable questions.

- If we make these systems smarter, when do they deserve rights?

- Could a sufficiently advanced DishBrain feel pain from the "chaotic noise" used to train it?

- Are we playing god by creating semi-living computer chips?

Currently, these cells are far too primitive to "suffer" in any meaningful way. They are less complex than the brain of a fly. But as we add more cells and more complex environments, scientists will need to tread very carefully. We are entering uncharted territory where the line between "device" and "living being" is getting blurry.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Is the DishBrain actually conscious? No, not in the way we understand it. It doesn't have thoughts, feelings, or self-awareness. It is "sentient" only in the sense that it can respond intelligently to sensory data, but it doesn't know it's playing a game.

2. Can DishBrain play modern games like Fortnite? Not yet! Pong is incredibly simple, requiring only basic "up or down" inputs. Modern 3D games require processing millions of pixels and complex strategies that are currently far beyond the capabilities of these small clusters of cells.

3. Why did they use both mouse and human cells? Scientists often use mouse cells as a baseline because they are well-understood and easy to work with. They used human cells (derived from stem cells) to see if there was a performance difference and to prove that human biological neural networks could also be integrated into these systems. Interestingly, some data suggested the human cells might have been slightly better learners!

4. Does it hurt the cells when they "lose" the game? There is no evidence that the cells feel "pain." The "punishment" for missing the ball is just disorganized electrical static. While the cells biologically prefer organized signals, equating this to human suffering would be a massive stretch at this stage of the technology.

5. Could this technology replace normal computers one day? It's unlikely to replace your laptop for checking standard emails or word processing. Silicon is very good at exact math and rigid logic. Biological computing will likely be used for specialized tasks where biology shines—like pattern recognition, adapting to new, messy data, or interfacing directly with the human body for prosthetics.

Conclusion

The DishBrain experiment is more than just a weird science headline. It is a tangible demonstration that intelligence—the ability to learn, adapt, and act—isn't magical. It's a biological process that we can observe, measure, and even integrate with our own technology.

By teaching neurons to play Pong, we haven't just created a gamer in a petri dish. We've taken the first tentative steps toward a future where our technology might one day be as adaptable, efficient, and perhaps even as "alive" as we are. As we continue to explore this synthesis of biology and silicon, we may find that the next great leap in computing won't come from a better microchip, but from the very building blocks of life itself.