The Moon. It hangs in our sky, a silent, gray sentinel. For all of human history, it’s been a symbol of dreams, of mystery, and of the ultimate "up there." We've visited, planted flags, and taken pictures. But visiting is easy. Staying is hard.

Why? Imagine packing for the longest camping trip in history. You’d need to bring every drop of water, every puff of air, and every gallon of fuel. For a permanent Moon base, this isn't just impractical; it's impossible. The sheer cost of launching that much "stuff" from Earth would bankrupt any nation. The only way to truly live on the Moon is to live off the land.

This concept is called In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU), and it’s the holy grail of space exploration. It means turning the "dead" rocks and dust of the Moon into the building blocks of life: water, oxygen, and fuel. For decades, this was science fiction. Now, the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program (CLEP) has unveiled a bold, integrated blueprint to make it a reality. They don't just want to mine the Moon; they want to install a fully robotic chemical factory that uses only sunlight and local soil to create a self-sustaining oasis.

This isn't just another proposal. It's a strategic plan that could fundamentally change our future in space. Let's deconstruct this ambitious claim.

Executive Summary: Unpacking the Grand Blueprint

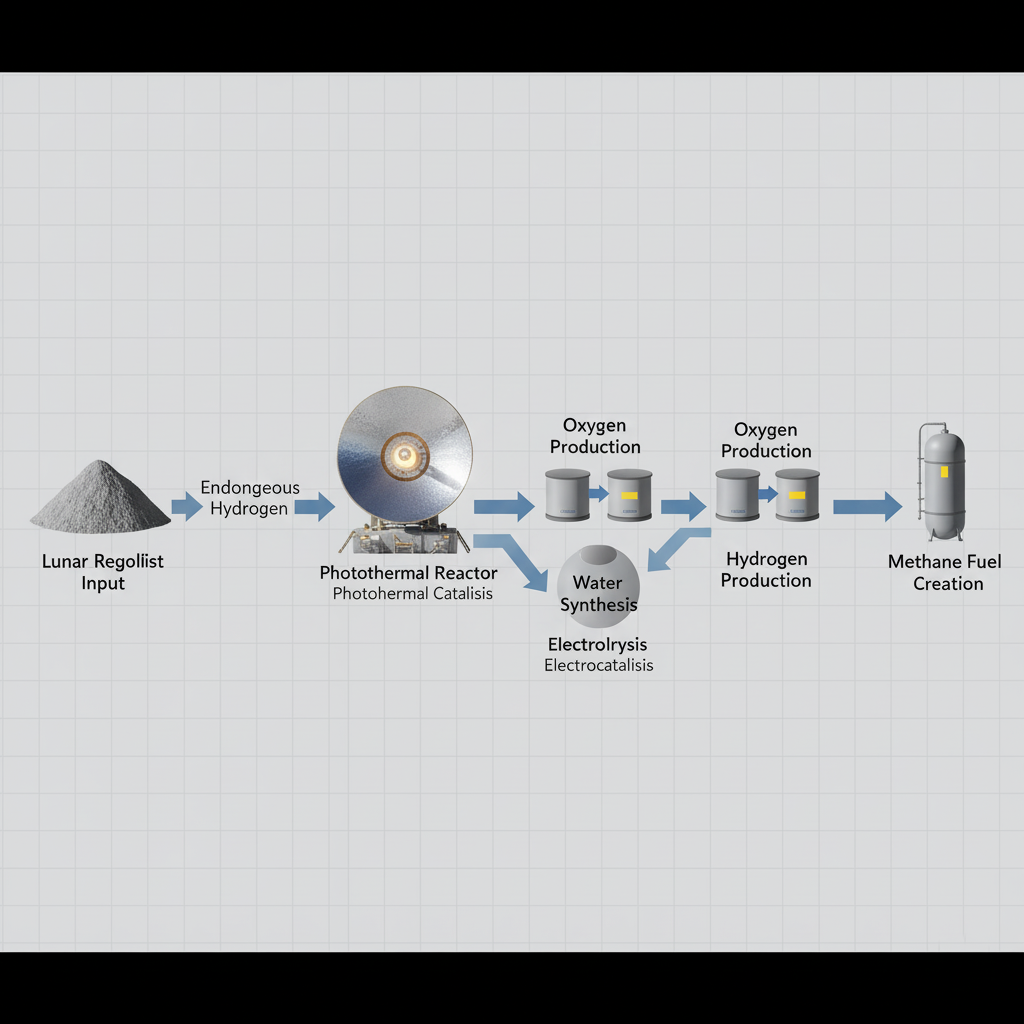

At its heart, the Chinese proposal is a model of stunning efficiency. The core claim is this: a single, integrated system can use lunar soil (regolith) and sunlight to sequentially produce oxygen, hydrogen, water, and even methane (rocket fuel).

This is a radical departure from older ideas, which usually involved separate, complex processes for each resource. Think of it this way: most plans were like building a separate factory for the power company, the water plant, and the gas station. China's plan is to build one machine that does it all.

They’ve nicknamed this concept "extraterrestrial photosynthesis," and it’s a brilliant comparison. Just as a plant on Earth uses sunlight to turn CO2 and water into sugar (energy) and oxygen, this system would use sunlight to "process" the chemicals locked inside the Moon's soil.

The entire blueprint rests on three core technological pillars, each feeding into the next:

- Photothermal Catalysis: Using sunlight for high-energy heat to crack open moon rocks and get oxygen.

- Endogenous Hydrogen: "Baking" trapped hydrogen out of the soil grains themselves.

- Electrocatalysis: Using electricity (from solar panels) to split the water you just made into fuel or recycle astronaut breath into methane.

This blueprint isn't just a vague idea; it's a specific, step-by-step industrial process designed for robots, aimed directly at building the foundation for the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), China's planned permanent base. They believe they’ve found the "magic rock" and the "magic recipe" to unlock it.

The All-in-One Factory: Photothermal Catalysis

What Is It, Really?

Let’s break down that mouthful of a term.

- "Photo" means light.

- "Thermal" means heat.

- "Catalysis" is the secret sauce. A catalyst is something that speeds up a chemical reaction without getting used up itself. Think of it as a "coach" for molecules, pushing them to react faster.

So, photothermal catalysis is a process that uses focused sunlight (for both its light and its intense heat) along with a catalyst to drive a chemical reaction.

How It Works on the Moon

Imagine a rover with a scoop. It digs up a shovel-full of gray lunar dust and drops it into a special reactor. A large, curved mirror, like a giant magnifying glass, captures the intense, unfiltered sunlight of space and focuses it onto the dust.

The temperature inside the reactor skyrockets, potentially over 1,000°C (1,832°F). But here’s the genius part: the Chinese strategy doesn't bring a catalyst from Earth. The lunar soil itself is the catalyst.

This superheated, catalyzed soil can now do amazing things. If you pipe in a little carbon dioxide (CO2)—perhaps captured from the breath of future astronauts—the system will use the heat and the catalytic soil to crack that CO2 apart. The result? You get pure, breathable oxygen (O2) and carbon monoxide (CO).

This is the first product in the pipeline: oxygen. You've just made air from sunlight and dirt. But this process is also the engine that drives the next step.

Tapping the Moon's Hidden Reservoir: Endogenous Hydrogen

The Water Problem

To make water (H2O), you need two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen. We just figured out how to get oxygen. But hydrogen? That’s the hard part.

For years, the main strategy (like NASA's Artemis program) has been to target the permanently shadowed craters at the Moon's poles. These craters are so deep the sun never shines in them. They are among the coldest places in the solar system, and we know they contain billions of tons of water ice, frozen solid and mixed with dust.

The problem? These craters are dark, incredibly cold (below -200°C or -328°F), and difficult to access. Operating machinery in that environment is a nightmare.

A Radically Different Solution

China's plan offers a brilliant alternative. They aren't going to the water; they're going to make it.

The Moon has no atmosphere, so for billions of years, it’s been blasted by the solar wind—a constant stream of particles from the Sun. A large part of this wind is protons, which are just the nucleus of a hydrogen atom. This hydrogen smashes into the lunar soil and gets trapped inside the mineral grains.

This trapped hydrogen is called "endogenous hydrogen" (meaning "originating from within"). It's not ice; it's hydrogen gas infused into the rock itself.

Remember that photothermal reactor heating the soil to 1,000°C? That same extreme heat does a second job. It "bakes" the soil so thoroughly that this trapped endogenous hydrogen is forced out. It outgasses from the mineral grains.

A collection system would capture this released hydrogen gas (H2). Now, the factory has both its ingredients:

- Oxygen (O2) from the photothermal catalysis.

- Hydrogen (H2) baked out of the soil.

Combine them, and you get the most precious resource in the solar system: pure, life-sustaining water (H2O). This is the "massive water generation" the plan claims. It’s not a gusher; it’s a steady, reliable trickle, produced anywhere the Sun shines, not just in a few dark craters.

The Robotic Chemist: Electrocatalysis for Unmanned Fuel Production

Beyond Water and Air

You have air to breathe and water to drink. You're alive. But you're not going anywhere. The next step to becoming a true spacefaring species is to create a "gas station" on the Moon. We need rocket fuel.

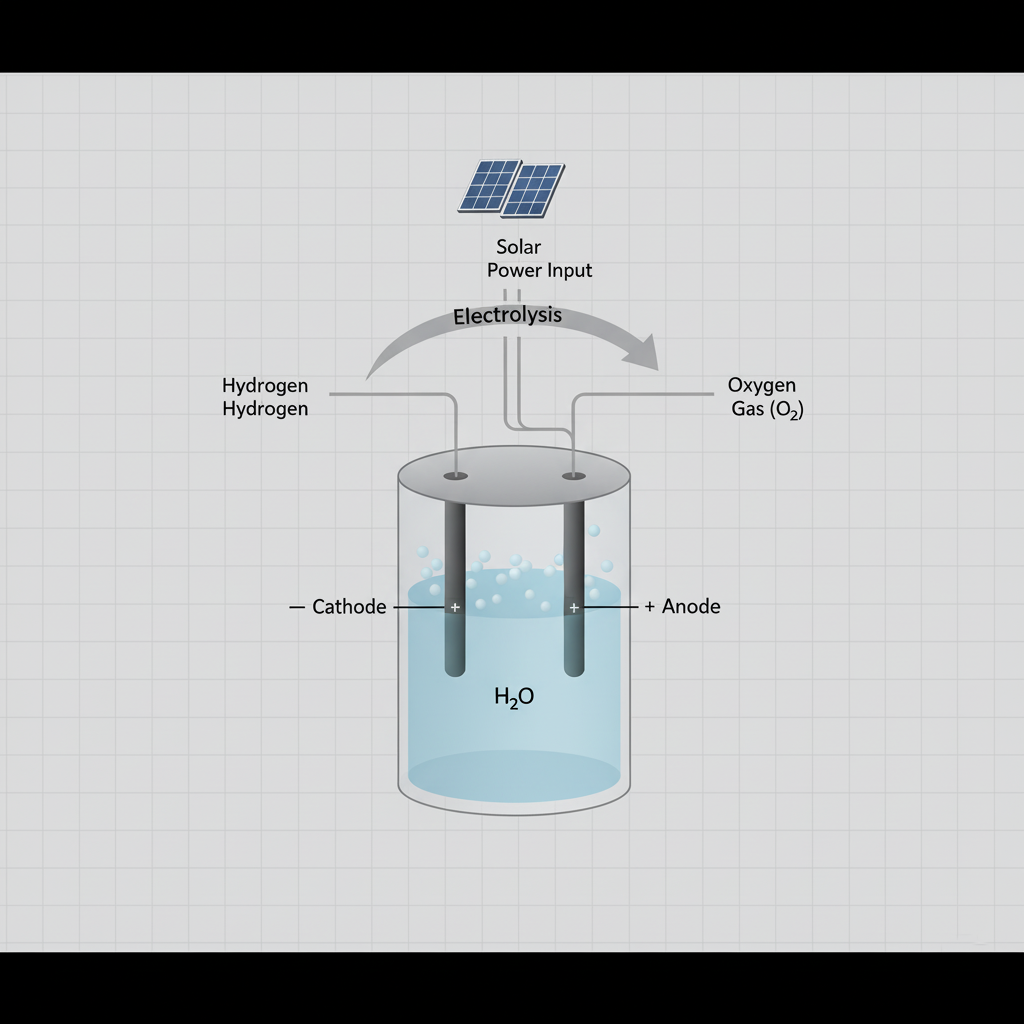

This is where the third pillar of the Chinese system, electrocatalysis, kicks in.

- "Electro" means electricity.

- "Catalysis" is our old friend, the reaction-speeding coach.

This process uses electricity—generated by large solar panels—to drive a chemical reaction.

Step 1: Making Rocket Fuel (Type 1)

The simplest rocket fuel is hydrogen (H2) and oxygen (O2). The system already has water. Using a familiar high-school chemistry process called electrolysis, the robotic factory can zap the H2O with electricity. The water molecules split apart, producing pure hydrogen gas (H2) and oxygen gas (O2).

These are cryogenically cooled, turned into liquids, and pumped directly into the tanks of a lunar lander or a transfer vehicle bound for Mars. This part of the system is designed to be unmanned. A fleet of rovers could spend the two-week lunar "day" (when the Sun is shining) scooping soil, making water, and splitting it into a massive fuel depot, all before the first human crew even arrives.

Step 2: Making Rocket Fuel (Type 2) and Recycling

Hydrogen is powerful, but it's hard to store. A more stable, storable fuel is methane (CH4). To make methane, you need hydrogen (H2) and carbon (C).

We have the hydrogen from splitting water. Where do we get the carbon?

- Astronauts: Humans exhale carbon dioxide (CO2). A lunar base will be a "closed-loop" environment, and this system is the perfect recycler. It can take that waste CO2, combine it with the hydrogen (using a catalyst), and produce methane (CH4) and more water (which goes back into the system).

- The Soil: The photothermal process from step 1 already produced carbon monoxide (CO). This can also be combined with hydrogen to create methane.

This unmanned fuel production is the ultimate value proposition. It means a rocket could land on the Moon with just enough fuel to get there, and then refuel for the trip home, or for a new mission to Mars. The Moon stops being a destination and becomes a refueling depot.

The Magic Moon Rock: Ilmenite and a Reality Check

This entire, elegant, three-step process sounds almost too good to be true. It hinges entirely on finding the right kind of soil. You can't just scoop any old gray dust. The system is optimized for one specific mineral: Ilmenite.

Why Ilmenite Is the Key

Ilmenite (chemical formula: FeTiO3) is an iron-titanium oxide. It's common in the dark "seas," or maria, on the Moon's surface—the very areas China's Chang'e missions have been exploring. China's Chang'e 5 mission, which returned samples in 2020, confirmed that lunar ilmenite is a perfect candidate.

Here’s why it’s the "key material":

- It’s Rich in Oxygen: It's an "oxide," meaning it's chemically loaded with oxygen. The photothermal heating breaks the iron-oxygen and titanium-oxygen bonds, releasing O2.

- It’s a Great Catalyst: The iron and titanium in Ilmenite are fantastic catalysts. They naturally speed up the reactions needed to break down CO2 and H2O. You don't need to ship a complex catalyst from Earth; the rock itself does the job.

- It Holds Hydrogen Well: Ilmenite's crystal structure is particularly good at trapping and holding onto the "endogenous hydrogen" from the solar wind.

Comparative Analysis: Why This Way?

Let's compare the two main strategies for getting water on the Moon.

| Strategy | Mining Polar Ice (e.g., Artemis) | Heating Ilmenite (e.g., CLEP) |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Restricted to a few dark, freezing craters at the poles. | Flexible. Can operate anywhere in the sunlit maria where Ilmenite is abundant. |

| Main Product | Water (H2O). | Integrated: Oxygen, Hydrogen, Water, and a pathway to Methane. |

| Process | Mechanical: Digging, heating, purifying abrasive ice-dust. | Chemical: High-temperature reactor, catalysis. |

| Pros | Direct, high-concentration source of water. | One system for all consumables. Uses the catalyst "for free" from the soil. |

| Cons | Extreme cold, darkness, abrasive dust is hard on machinery. | Needs very high temperatures. Yield of hydrogen per kilo of soil is low (requires processing tons of soil). |

The Chinese strategy is, in essence, a bet on chemical engineering over brute-force mining. They are betting that a more complex, high-tech process is ultimately more sustainable than a simpler resource that's in a much harder-to-reach place.

The Dragon's Reach: China's Lunar Ambition

This scientific blueprint cannot be separated from its Strategic Context: The Chinese Lunar Exploration Program (CLEP).

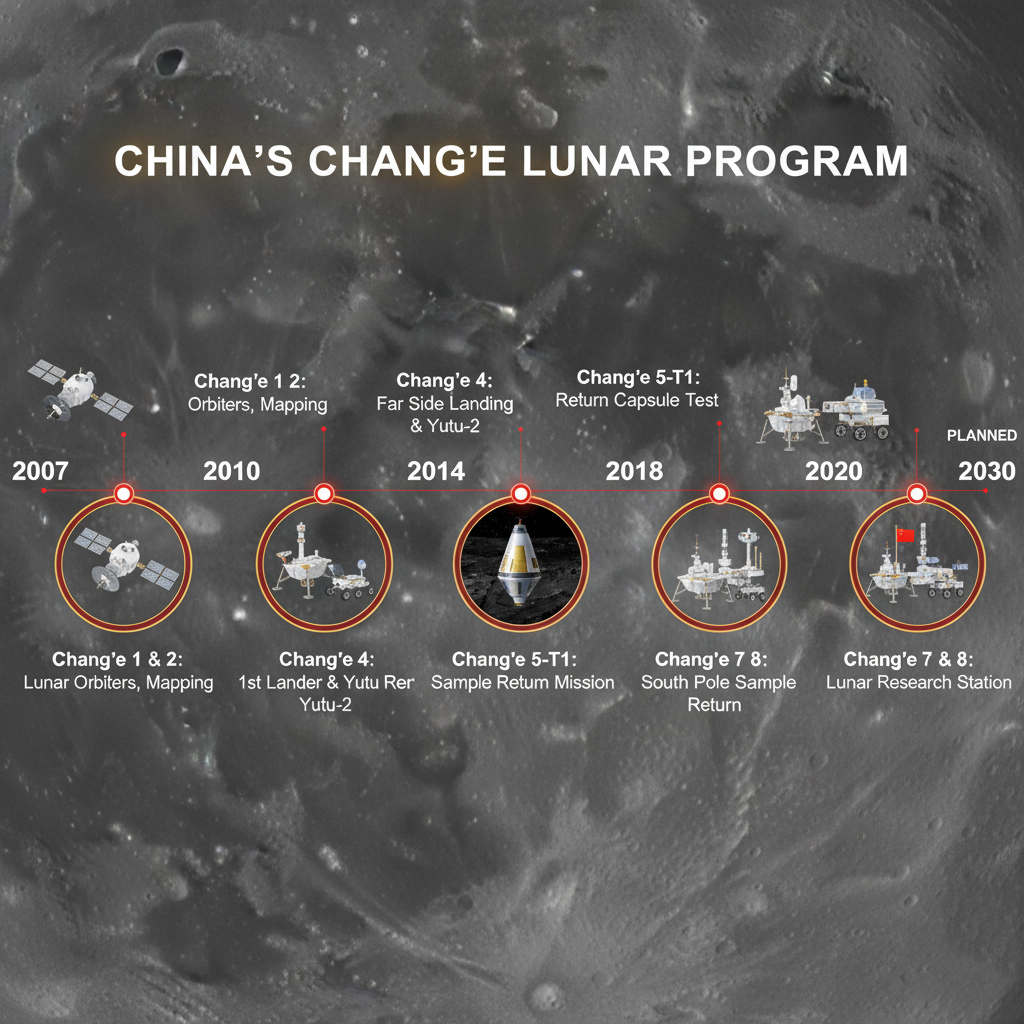

This isn't just a paper exercise. This is the "how-to" manual for China's next decade in space. The CLEP, or Chang'e Program, has been a methodical, step-by-step success.

- Chang'e 1 & 2 (2007, 2010): Orbited and mapped the Moon.

- Chang'e 3 (2013): Landed the Yutu (Jade Rabbit) rover.

- Chang'e 4 (2019): Achieved a historic first: landing on the far side of the Moon.

- Chang'e 5 (2020): Landed, drilled, scooped samples, and returned them to Earth—the first time in 44 years.

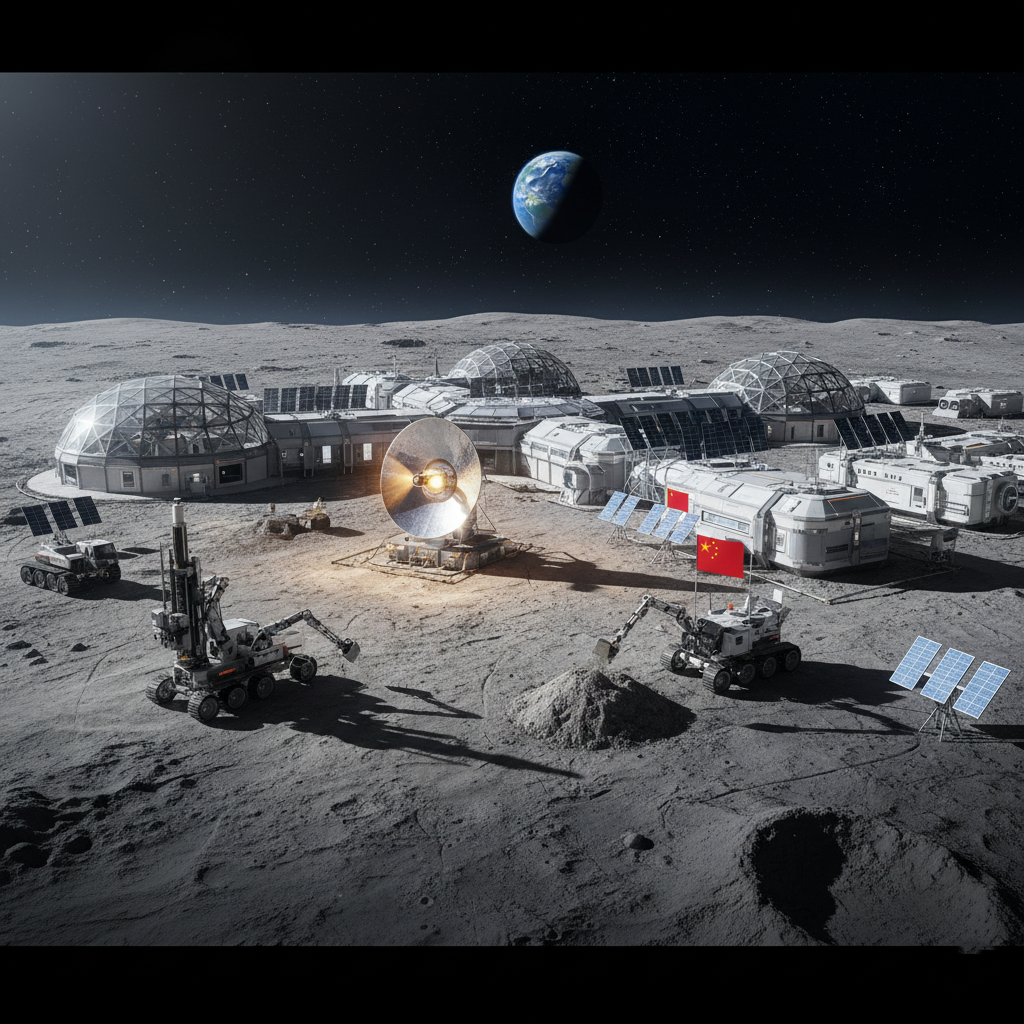

Those returned samples are what gave them the hard data on Ilmenite and its properties. Now, the next missions—Chang'e 6, 7, and 8—are all designed to lay the groundwork for the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS).

The ILRS is China's (and Russia's) answer to the US-led Artemis Program. But while Artemis is focused on a "flags and footprints" return for astronauts, the ILRS is being designed from day one as a permanent robotic base that will later be crewed.

To have a permanent base, you must have ISRU. This photothermal/electrocatalysis system is the engine China plans to build that base around. The nation that controls the Moon's resources—its water, its oxygen, its fuel depots—effectively controls the Moon. This is a new kind of "space race," but it's not for prestige. It's for territory and resources.

The Hardest Part: Feasibility, Bottlenecks, and Implementation Challenges

This all sounds incredible on a whiteboard. But space is hard. The Moon is actively hostile to machines. There are several massive, real-world hurdles that must be overcome.

Bottleneck 1: The Dust From Hell

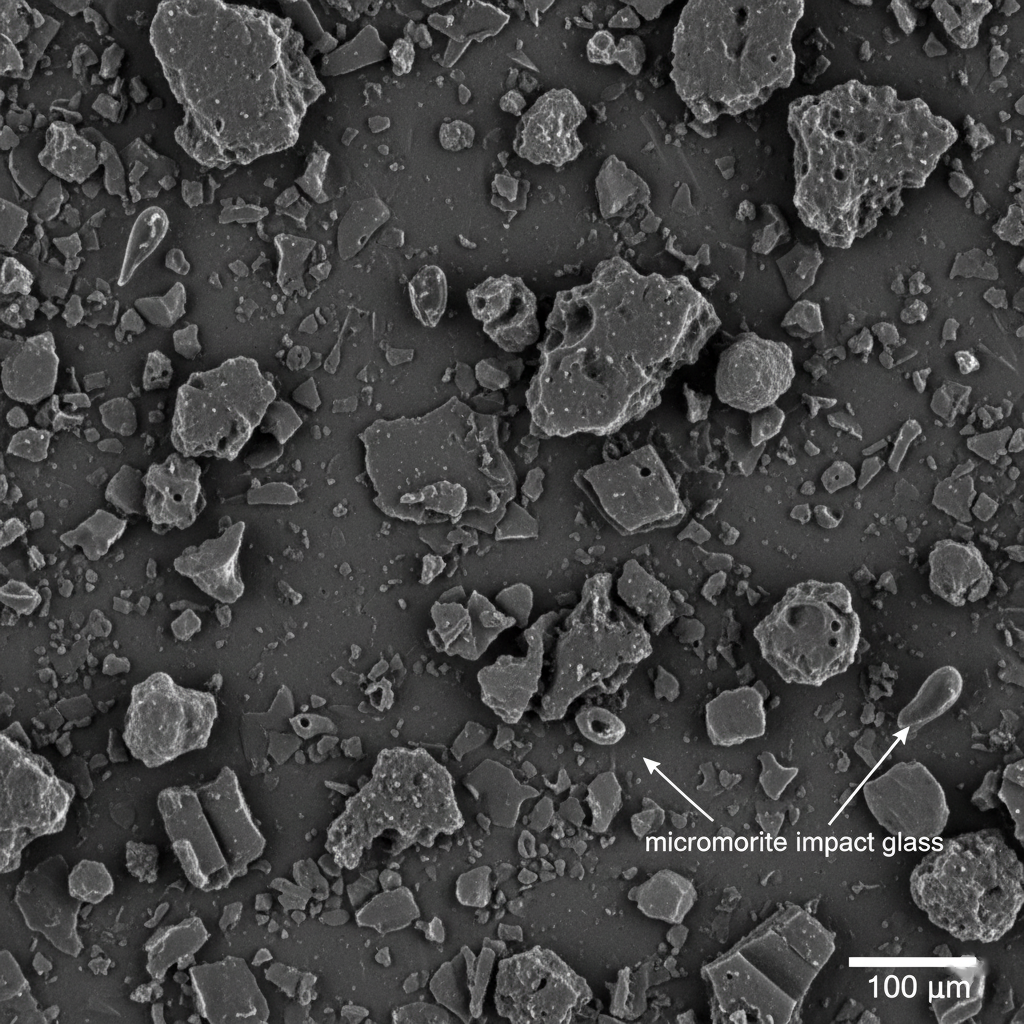

The single biggest challenge for any Moon mission is lunar regolith. It is not soil. It's a layer of ultra-fine, glass-sharp, abrasive dust, forged by billions of years of micrometeorite impacts.

- It's Abrasive: It grinds down seals, gears, and any moving parts.

- It's Clingy: It's electrostatically charged, so it sticks to everything—solar panels, camera lenses, space suits.

- It's Toxic: It's harmful to breathe.

A system that must constantly scoop, transport, and heat this "death dust" will be in a non-stop battle against maintenance. How do you keep the reactor from clogging? How do you protect the high-precision mirrors? This is the foremost engineering challenge.

Bottleneck 2: The Need for Heat and Power

This system is power-hungry. The photothermal part is clever because it uses sunlight directly for heat, which is more efficient than using solar panels to make electricity to run a heater. But "efficient" doesn't mean "easy." Focusing sunlight to 1,000°C requires complex, precision-moving mirrors that must track the sun perfectly, all while... not getting covered in dust.

The electrocatalysis part needs massive amounts of raw electricity, which means huge solar arrays.

Bottleneck 3: The Long, Cold Night

A spot on the Moon's equator has 14 days of continuous, harsh sunlight, followed by 14 days of continuous, freezing-cold night.

- During the day, the system can run flat-out.

- During the night, temperatures plummet to -173°C (-280°F). The entire factory would freeze solid.

This means the system either needs massive batteries (heavy and expensive) or a small nuclear power source (like a Kilopower-style reactor) to survive the night. Or, it must be designed to completely shut down, freeze, and then reliably "reboot" itself 14 days later—a process that puts immense stress on any machine.

Bottleneck 4: 100% Robotic Autonomy

This chemical plant must run without human help. It needs an advanced AI to be the "factory foreman." It must be able to find good Ilmenite patches, diagnose a stuck valve, reverse a clogged filter, and manage the complex chemical flow on its own. We have never, ever attempted automation at this scale on another world.

Concluding Synthesis: From Gray Dust to a Blue Future

The Chinese proposal for integrated resource production on the Moon is more than just a clever piece of science. It is a philosophy of exploration. It’s a bold declaration that the future in space belongs not to those who can pack the most, but to those who can adapt the best.

By identifying a single mineral, Ilmenite, as the key, they have designed an elegant system that turns the Moon's greatest "problems"—its harsh sunlight and its weird soil—into its greatest solutions. It’s a plan that sees the Moon not as a dead rock to be visited, but as a living, dynamic resource that can be cultivated.

This "extraterrestrial photosynthesis" is the heart of China's ambition. It’s the engine that will power their lunar base, refuel their Mars missions, and perhaps one day supply a bustling cislunar economy.

The challenges are monumental. The abrasive dust, the extreme temperatures, and the sheer complexity of robotic chemistry are hurdles that could doom the entire project. But if they succeed? If a fleet of rovers one day begins to quietly brew water and fuel from nothing but sunlight and gray dust, it will mark a turning point in human history. It will be the moment we stopped being visitors to the cosmos and truly learned to live there.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why is Ilmenite so special compared to other moon rocks? A: Three reasons! 1. It's an oxide, so it’s naturally packed with oxygen that can be released with heat. 2. Its iron and titanium content make it a natural catalyst, so you don't have to bring one from Earth. 3. Its structure is great at trapping hydrogen from the solar wind, which is the key ingredient for making water.

Q: Is this system better than just mining the ice at the Moon's poles? A: It's a trade-off. Mining ice is more direct—you find H2O and you melt it. But it restricts you to tiny, dark, freezing-cold craters. This Chinese system is more flexible because it can work anywhere in the sunlit regions, and it's more integrated because it produces oxygen, hydrogen, and fuel from one machine, not just water.

Q: How much water can this system actually make? A: The concentration of hydrogen in the soil is very low. You would have to "bake" several tons of lunar soil to produce a single liter of water. This system isn't a firehose; it’s a slow, steady drip. But on the Moon, where a liter of water costs $1 million to launch from Earth, a steady drip is revolutionary. It's about accumulation over time by robots that don't get tired.

Q: What is the single biggest challenge to making this all work? A: By far, the lunar dust (regolith). It's not like sand on Earth. It's microscopic, sharp as glass, and electrostatically sticky. It will get into everything—gears, seals, joints, and reactors. Designing a robotic chemical plant with moving parts that can survive this brutal dust for years is the number one engineering problem.

Q: Does this mean China is "winning" the new space race? A: It means they are running a different kind of race. The US-led Artemis program is currently focused on the challenge of getting human astronauts back to the Moon quickly. China's ILRS program is focused on the challenge of building permanent, robotic infrastructure first. This ISRU system is the cornerstone of that infrastructure. It’s a long-term strategy, and if it pays off, it will give them a massive advantage in sustaining a permanent presence.