Imagine a bustling metropolis where six-year-olds take the subway alone, navigating complex transit systems without a parent in sight. Picture a café where you can leave your laptop on a table while you order, fully confident it will be there when you return. This isn't a utopian fantasy; for millions of people in Japan, it is daily life. Japan’s reputation as one of the safest countries on Earth is legendary. It is a benchmark that other nations look toward with envy, wondering how a modern, densely populated society can function with so little apparent chaos.

But why should you care about the inner workings of a country that might be thousands of miles away? Because Japan’s story is not just about low crime statistics; it is a fascinating case study in human behavior, social engineering, and the hidden costs of a perfectly orderly society. By understanding how Japan achieved this "miracle," we gain valuable insights into the trade-offs between absolute safety and individual freedom.

This article will take you behind the curtain of this celebrated safety. We will validate the impressive statistics, uncover the cultural and structural pillars that hold this order in place, and shine a light on the dark corners that are often ignored. We will connect these abstract concepts to the real, sometimes heartbreaking, lived experiences of Japanese citizens—from toddlers running errands to elderly seniors who find more community in prison than in their own homes. Finally, we will look at the cracks forming in this carefully constructed system as it faces the modern challenges of the 21st century.

Part 1: The Reality of a "Low-Crime" Nation

Before we dig into the how and why, we must establish the what. Is Japan really as safe as they say, or is it just good PR?

1.1 The Statistical Benchmark

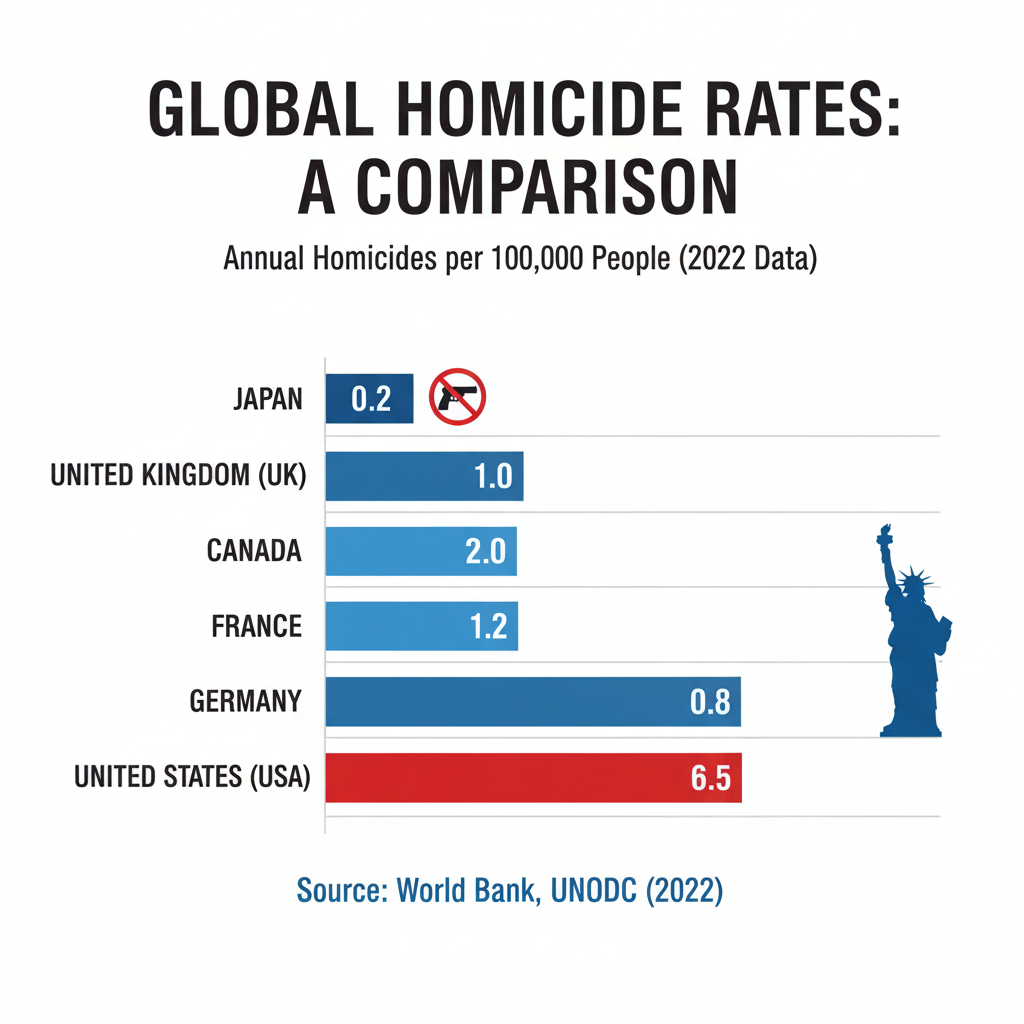

The short answer is yes, the safety is real, especially when it comes to the crimes that scare people the most. Japan consistently ranks as having one of the lowest rates of intentional homicide in the world. When you compare Japan to the United States, the difference is staggering—a massive order of magnitude separates the lethal violence rates of the two nations.

It’s not just murder, either. Over the last decade, other violent crimes like robbery and theft have been on a steady downward trend. While comparing international crime data can be tricky—different countries have different laws and ways of counting crimes—Japan’s numbers are so consistently low across the board that they cannot be dismissed as mere statistical noise.

1.2 A Palpable Sense of Safety

Statistics are just numbers on a page until you feel them in real life. In Japan, these low numbers translate into a palpable, almost surreal sense of security. Visitors to mega-cities like Tokyo often describe the atmosphere as startlingly relaxed.

This deep-seated public trust allows for social behaviors that would be considered wildly dangerous in many other parts of the world. The most famous example is Japanese children. It is common to see very young elementary school students, sometimes even toddlers, walking to school or running errands entirely on their own. This cultural phenomenon is so unique that it spawned the hit TV show "Old Enough!", which documents little kids successfully navigating the big world solo.

Adults, too, act on this trust. Walking away from a valuable item in a public space isn't an invitation for theft; it’s just a normal part of a café visit. This isn't naïveté; it's a learned behavior reinforced by decades of experiencing a genuinely safe environment.

1.3 A Modern Achievement, Not Ancient History

There is a common misconception that Japan is safe because of some ancient, unbreakable cultural code. This idea, often rooted in theories of "Japanese uniqueness" (Nihonjinron), is too simplistic. History tells a different story.

Japan’s current low-crime status is actually a relatively recent achievement, really taking hold in the late 1960s. If you look back at the years immediately after World War II (1945-1952), Japan was a very different place. The country was in ruins, society was fractured, and life was described as "Hobbesian"—nasty, brutish, and short. People committed crimes just to survive.

The era of safety we know today didn't magically appear; it was built alongside Japan’s massive economic boom between 1952 and 1990. This proves that low crime isn't just in the "blood" of a nation. It is a contingent outcome—something that happens only when specific social and economic structures are built and maintained.

Part 2: The Three Pillars of Social Order

If safety was built, what are the bricks? Japan’s order rests on three massive foundational pillars that blend culture, community policing, and strict laws.

2.1 Pillar One: Culture as Control

The most powerful police force in Japan isn't wearing a uniform; it's inside everyone's head.

The Power of Wa (Harmony)

At the heart of Japanese social life is the concept of Wa, or group harmony. From a very young age, children are socialized to think of themselves as part of a collective whole. You are taught to always consider how your actions will affect the group—your family, your class, your company.

This acts as a massive "collective conscience." Anti-social behavior isn't just breaking a rule; it's breaking the harmony of the group. The intense social pressure to avoid "standing out" or causing trouble acts as a powerful psychological brake on criminal impulses.

Shame vs. Guilt

While Western cultures often rely on guilt (an internal feeling of "I did something bad"), Japan relies heavily on shame (an external feeling of "I have disgraced my group"). Criminologists call this "reintegrative shaming." The fear of bringing dishonor to your parents or your colleagues is often a far stronger deterrent than the fear of jail time. People are bonded tightly to their social groups, and the threat of being severed from them is terrifying.

Economic Factors

These cultural norms worked best when everyone was on a similar economic footing. For decades, Japan had low wealth inequality and very low unemployment. When people aren't desperate for money and feel like they are all in the same boat, there is less incentive to rob your neighbor.

2.2 Pillar Two: The Friendly Neighborhood Kōban

Culture is backed up by a highly visible, hyper-local police presence known as the Kōban system.

Everyday Policing

A Kōban is a small police box found in almost every neighborhood. The officers stationed there, affectionately called Omawari-san (Mr. Policeman), don't just wait for 911 calls. They are deeply integrated into the community fabric.

Their job is incredibly varied. They give lost tourists directions, handle lost-and-found items, and even conduct routine home visits to check on elderly residents. By patrolling on bicycles and being constantly accessible, they build deep reservoirs of public trust. They aren't faceless enforcers; they are part of the neighborhood.

The "Beautiful Windows" Movement

A great example of this proactive approach is the "Beautiful Windows Movement" in Tokyo’s Adachi Ward. Faced with a bad reputation for crime, the ward didn't just hire more SWAT teams. They partnered with citizens to clean up the streets, literally making the ward beautiful while cracking down on minor disorders (based on the "Broken Windows Theory"). The result was a massive drop in crime and a huge boost in residents' sense of pride and security.

2.3 Pillar Three: Strict Laws and Deterrence

The final pillar is a legal system that prioritizes social stability over individual liberty.

Zero Guns, Almost Zero Gun Violence

Japan has some of the strictest gun control laws on the planet. You can't just buy a handgun for protection. Even getting a hunting rifle requires rigorous background checks, mental health evaluations, drug tests, and full-day classes. The result? A nation almost entirely free of gun violence. The message from the government is clear: the safety of the group is far more important than your individual right to own a weapon.

Hardline on Drugs

The same goes for drugs. Japan has a zero-tolerance policy. Being caught with even a tiny trace of cannabis can lead to severe jail time, deportation for foreigners, and total social ostracization. It is a harsh trade-off that keeps drug-related street crime very low.

Part 3: The 'Hidden Trade-Offs' of Justice

Every system has a price. In Japan, the price of extreme order is often paid by those who find themselves accused of a crime.

3.1 The 99% Conviction Rate

Japan is famous—some would say infamous—for having a conviction rate that hovers around 99%. On the surface, this looks like supreme efficiency. In reality, it’s a carefully engineered statistic.

This high rate is largely due to "prosecutorial discretion." Japanese prosecutors do not like to lose. They are often understaffed and have tight budgets, so they only bring cases to trial if they are absolutely, 100% certain they will win. They filter out any case with even a shred of ambiguity. If you are actually taken to court in Japan, the system has already decided you are guilty.

3.2 "Hostage Justice" (Hitojichi Shihō)

How do prosecutors get so certain? They use a controversial pre-trial system that critics call "Hostage Justice."

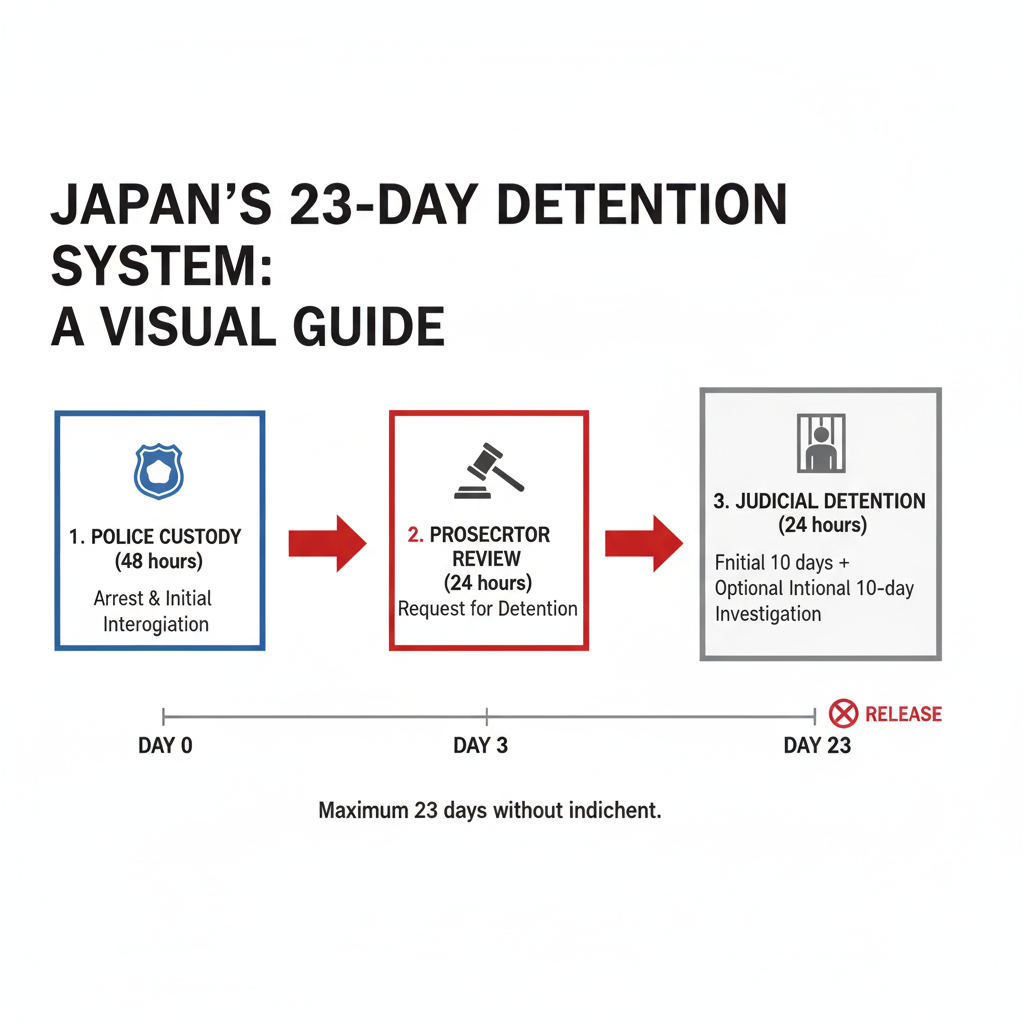

If you are arrested, police can hold you for up to 23 days before they even officially charge you with a crime. During this time, you can be interrogated for hours every day without a lawyer present. Your lawyer can visit you, but they can't be in the room when the police are questioning you.

Worse, you will likely be denied bail if you deny the charges. The system is designed to break your will. Suspects often suffer severe mental duress in solitary confinement. Prosecutors might imply—or outright state—that the only way to get out of this detention is to sign a confession.

This system works very well for keeping stats high, but it has led to tragic cases of innocent people confessing to crimes they didn't commit, just to end the nightmare of detention.

Part 4: Statistical Blind Spots

The shiny "low-crime" exterior also masks certain types of crimes that don't make it into the headline statistics because they are underreported or ignored to maintain social harmony.

4.1 The Silence on Gender-Based Violence

Japan’s safety narrative often overlooks the reality for women. There is a "hidden number" of violent crimes in the domestic sphere. Cultural pressure to maintain family Wa (harmony) means that domestic violence is frequently kept secret.

In public, chikan (groping on trains) is distressingly common. While it is technically a crime, it is often trivialized. Police have historically discouraged victims from filing formal reports, preferring to settle things quietly to avoid embarrassing anyone. This systemic suppression keeps the official crime numbers low while ignoring the real victimization occurring daily.

4.2 White-Collar Crime

Japan is definitely not a "low-crime" nation when it comes to corporate malfeasance. Serious white-collar crimes—fraud, accounting scandals, insider trading, and bid-rigging—occur frequently.

Historically, many of these corporate crimes had links to the Yakuza (organized crime). Major companies have been caught paying off Yakuza groups to keep them quiet or using them to harass tenants out of buildings. These sophisticated crimes are harder to see than a street mugging, but they do immense damage to society.

Part 5: Emerging Challenges and the New Face of Crime

The 20th-century model that built safe Japan is now struggling to keep up with 21st-century realities. The nature of crime is changing rapidly.

5.1 The Death of the Old Yakuza

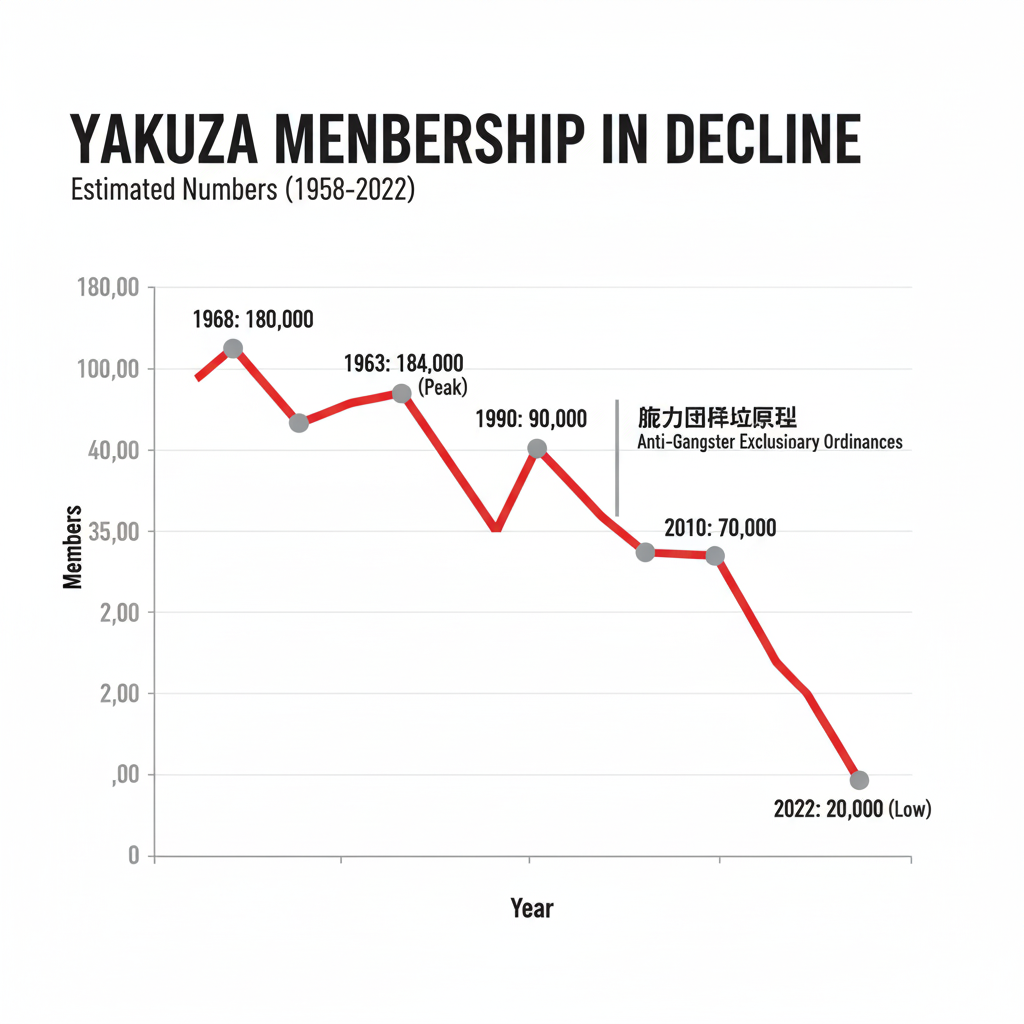

For decades, the Yakuza were the face of Japanese organized crime. They were visible, hierarchical, and operated almost like corporations. But in the last 15 years, the government crushed them with "Exclusion Ordinances." These laws made it illegal for anyone to do business with a known Yakuza member—you couldn't even rent them an apartment or sell them a cell phone.

It worked. Yakuza membership has plummeted. The remaining members are old, graying men, and young people have zero interest in joining such an outdated, restricted lifestyle.

5.2 The Rise of Tokuryū

Nature abhors a vacuum. As the Yakuza faded, a new, more dangerous threat emerged: Tokuryū.

This term combines the Japanese words for "anonymous" and "fluid." These aren't organized gangs with codes of honor. They are ad-hoc, digital criminal groups that form online for specific jobs and then vanish. They recruit young, desperate people through "dark part-time jobs" (yami-baito) on social media to commit smash-and-grab robberies or complex fraud scams.

The Kōban system doesn't know how to fight them. You can't bike around a neighborhood and find an anonymous hacker group that only exists on an encrypted app.

5.3 The Tragedy of Elderly Crime

Perhaps the most heartbreaking challenge is the massive spike in crime among senior citizens. Japan has the oldest population in the world, and its elderly crime rate has quadrupled in twenty years.

Why? It’s a social welfare crisis disguised as a crime wave. Many seniors are isolated, poor, and incredibly lonely. They have no family who talks to them and no place in society. In a tragic paradox, they commit petty crimes like shoplifting on purpose so they can go to prison.

For these seniors, prison offers three meals a day, shelter, and most importantly, a community of other people to talk to. Prisons are turning into nursing homes, with guards acting as caregivers. It is a stark sign that the social bonds that once held Japan together are fraying for its most vulnerable citizens.

Part 6: Conclusion

Japan’s reputation for safety is well-earned, but it is not magic. It is the result of a specific, engineered system built on cultural pressure, community policing, and strict laws. It is a system that has delivered incredible public peace, but at the cost of individual rights in the justice system and by sometimes turning a blind eye to less visible suffering.

Today, that system is under immense strain. The community bonds are weakening, evident in the lonely seniors seeking refuge in jail. The old policing methods are struggling against fluid, digital crime. Japan remains an incredibly safe country, but it is facing a future where its 20th-century solutions may no longer be enough to solve its 21st-century problems.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Is it really safe for tourists to travel alone in Japan? Yes, it is generally very safe for tourists, even those traveling alone. The risk of violent crime is extremely low compared to most other countries. However, standard common sense should still apply, especially in nightlife districts.

2. If the conviction rate is 99%, does that mean everyone arrested goes to jail? No. The 99% rate only applies to cases that actually go to trial. Prosecutors drop many cases before they ever reach court if they aren't absolutely sure they can win.

3. What are "dark part-time jobs" (yami-baito)? These are illegal "gigs" advertised on social media, often promising high pay for easy work. They are used by modern criminal groups (Tokuryū) to recruit young people to act as disposable labor for robberies or fraud schemes.

4. Why do elderly people want to go to prison in Japan? Many elderly offenders are motivated by extreme loneliness and poverty. They find that prison provides them with basic necessities like food and shelter, as well as a sense of community they lack in the outside world.

5. Does regular Japanese police carry guns? Yes, uniformed officers do carry firearms. However, they very rarely use them. The emphasis is heavily placed on martial arts (like Judo or Kendo) and de-escalation tactics rather than lethal force.