Imagine a school day. Does it start with a jolt of anxiety about a big standardized test? Does it end late at night, your brain foggy, as you try to finish a mountain of homework? For many students around the world, this is just... normal. It’s the grind. We’re often told that this pressure, this competition, is the only way to succeed, the only way to build a "good" future.

Now, picture a different kind of school.

Picture a place where kids don't start formal classes until they're seven. A place where, even in 9th grade, homework is minimal, maybe 30 minutes a night. Picture a school day with shorter classes and longer breaks—15 minutes of fresh air and play for every 45 minutes of learning. And here’s the most shocking part: there are almost no standardized tests. None. Students aren't ranked against each other, and schools aren't ranked against other schools.

It sounds like a fantasy, right? It must be a recipe for failure.

Except it’s not. This is the real, everyday reality of the education system in Finland. And for decades, this seemingly relaxed, stress-free approach has produced some of the highest-achieving, most well-adjusted, and most literate students on the planet.

How is this possible? How does "less" equal "more"?

Finland’s success isn't a magic trick. It's not about one simple fix. It is a completely different way of thinking about what school is for. It's a system built not on competition and data, but on trust, equity, and the well-being of the whole child. Get ready to question everything you thought you knew about education. We’re going to pull back the curtain on the Finnish model, from its core philosophy to the teachers who run it and the support systems that ensure no one is left behind.

The Philosophical and Structural Foundation: Building a School System on Trust

Before you can build a house, you need a blueprint and a strong foundation. The Finnish education "house" is built on a philosophical foundation that is radically different from most others.

Guiding Principles of the Finnish Education Model

If you asked a Finnish official what the "goal" of their school system is, they wouldn't say "to get the highest test scores in the world." They would say something like, "to ensure every child has an equal opportunity to become a good, well-rounded citizen." This philosophy is built on a few core beliefs.

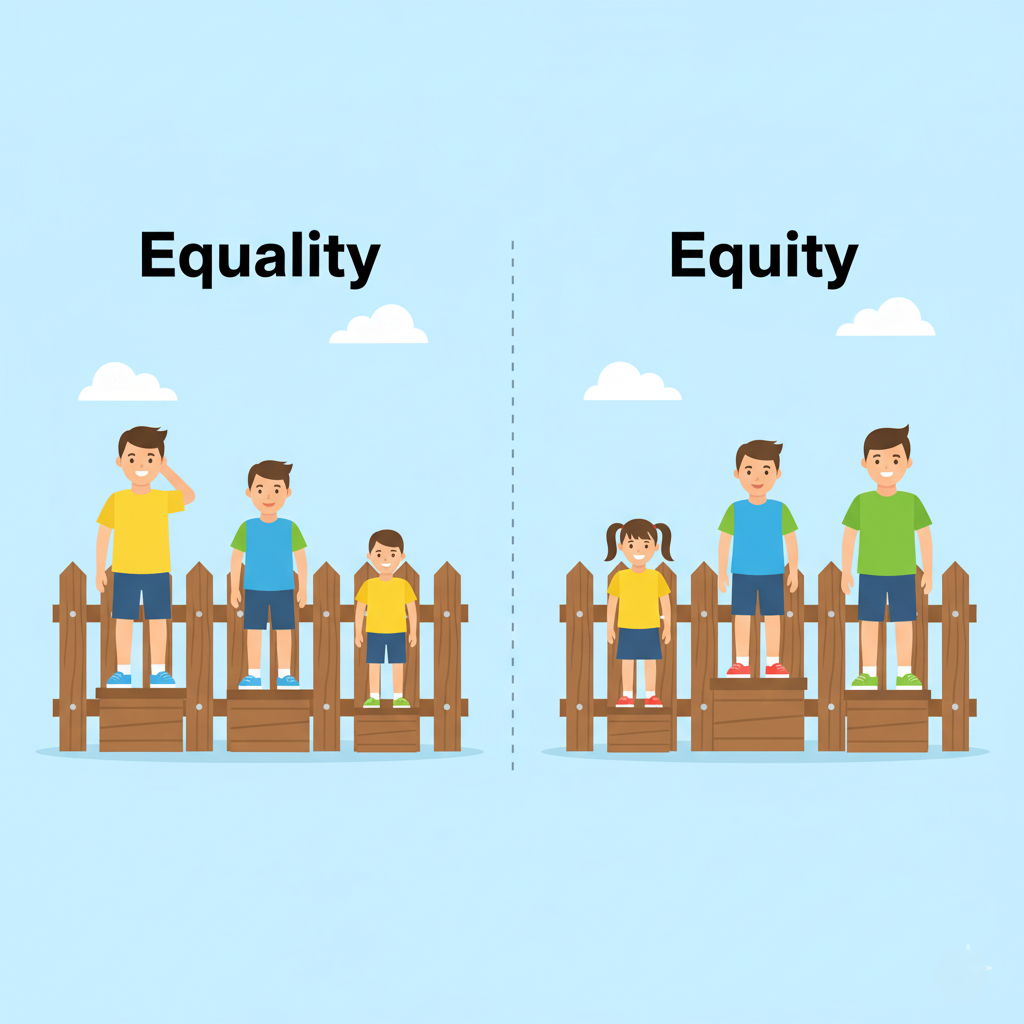

- Equity is the North Star: This is the single most important concept. But "equity" does not mean "equality." Equality means giving every student the exact same thing—the same book, the same test, the same amount of time. Equity, on the other hand, means giving every student what they individually need to succeed. It’s a subtle but powerful difference. Think of it like this: equality is giving everyone a size 9 shoe. Equity is making sure everyone has a shoe that actually fits their foot. In Finland, this means the system pours its resources—money, time, and its best teachers—into the students and schools that need the most help. The goal isn't to create a few "superstar" students; it's to raise the entire average, to make sure everyone finishes with the skills they need.

- Trust Over Control: This is the bedrock. The entire system runs on trust. The national government trusts the local towns (municipalities) to run their schools properly. The municipalities trust the principals. The principals trust the teachers. And, most importantly, the teachers trust their students. This trust means there is no need for a massive, top-down bureaucracy of inspectors and regulators. No one is hovering over a teacher's shoulder with a checklist. This trust unleashes a powerful sense of professionalism and responsibility.

- Well-being Before Academics: The Finns believe a child who is anxious, hungry, or stressed cannot learn. It's that simple. Therefore, the primary job of the school, especially in the early years, is to ensure a child is happy, healthy, and safe. They see education as a tool for personal development and finding joy, not just for economic competition.

Governance, Funding, and System Architecture

So, how do they pay for all this? It's simple: everyone pays for it, and everyone gets to use it.

The entire system, from daycare all the way through university, is 100% publicly funded through taxes. There are no private schools in the "basic education" (grades 1-9) system. You cannot "buy" a better education for your child. The richest kid and the poorest kid in a neighborhood go to the same high-quality local school. This is equity in action. It completely removes the competition and stress of "getting into" a good school. Every school is a good school.

The governance is also unique. It’s highly decentralized. The Finnish National Agency for Education sets the "National Core Curriculum," but this document is not a thick rulebook. It's a broad, 30,000-foot view of the goals and values of education. It outlines the competencies students should learn, like "learning to learn," "cultural competence," and "managing daily life."

Then, it's up to the local towns and the teachers themselves to decide how to meet those goals. They choose their own textbooks, design their own lesson plans, and structure their own school days. They are treated as the experts they are.

The Central Role of the Educator: The "Best of the Best"

If you're going to build a system based on trusting teachers, you’d better make sure your teachers are incredible. In Finland, they are.

Teacher Status, Selection, and Education

In many countries, people might joke, "Those who can't, teach." In Finland, the saying is, "Those who can, teach."

Teaching is consistently ranked as one of the most respected and sought-after professions, right alongside doctors, lawyers, and engineers. It's not seen as a "backup plan"; it's a "dream job." Because the job is so respected, it's incredibly competitive. Getting into a primary school teacher education program is harder than getting into law or medical school. Only about 10-15% of all applicants are accepted. The system is designed to select only the most passionate, capable, and dedicated candidates.

Once accepted, their education is rigorous and, like everything else, completely free. Every single teacher in Finland, from the 1st-grade teacher to the high school physics teacher, must hold a Master's degree. This isn't just a Master's in "teaching." It's a research-based degree, often from a university's top academic department. They don't just learn what to teach (like math or history); they study how people learn. They dig deep into educational psychology, cognitive science, and subject-specific pedagogy. They are, in effect, learning scientists. They write a Master's thesis, contributing original research to the field before they ever lead a classroom of their own.

Professional Autonomy and Practice

This intense training is what makes the "trust" model work. Because teachers are so highly educated and selected, the system grants them enormous professional autonomy.

This is what it looks like in practice:

- No Scripts: Teachers are not handed a script or a pre-packaged curriculum they must follow. They use the broad national goals to design their own unique, creative lessons.

- No Inspections: There are no "school inspectors" who show up to judge a teacher's performance. The principal is a colleague and a pedagogical leader, not a "boss" who does high-stakes evaluations.

- Collaborative Culture: Teachers spend less time in front of students than in many other countries. Their contract includes several hours every week dedicated to collaborative planning with their colleagues. They work in teams to design projects, discuss struggling students, and improve their craft.

- Same Teacher, Long Time: It is very common for a teacher to stay with the same group of students for multiple years (a practice called "looping"). This allows them to build incredibly deep, trusting relationships. They know each student’s strengths, weaknesses, and family situations. They're not just a teacher; they're a mentor.

This autonomy and respect mean that teachers stay in the profession. The teacher burnout and turnover rates that plague other countries are almost non-existent in Finland. They are treated as professionals, and so they act as professionals.

Curriculum, Pedagogy, and the Learning Process: "Less Is More"

So, what does learning actually look like in a Finnish classroom? You won't see rows of students silently memorizing facts for a test. You're more likely to see small groups of students working on a complex project, laughing with their teacher, or even outside building something.

The National Core Curriculum and Local Adaptation

As mentioned, the national curriculum is a flexible guide, not a rigid set of rules. It emphasizes "learning to learn." The goal is not to have students memorize the periodic table; it's to have them understand how to think like a scientist.

This flexibility allows for incredible creativity. Teachers adapt the curriculum to their students and their environment. A school in northern Lapland might use the local reindeer-herding economy to teach biology, math, and social studies. A school in the capital, Helsinki, might focus a project on urban design and public transportation. Both are meeting the same national goals, but in a way that is relevant and engaging for their specific students.

Starting in 2016, Finland made waves by introducing "phenomenon-based learning." This is a move away from traditional, separate subjects. Instead of having one hour of "math" and then one hour of "history," schools are required to have at least one extended period per year where students tackle a big, real-world phenomenon or topic.

For example, a 7th-grade class might do a six-week project on "Immigration." This single project would involve:

- Social Studies: Researching the history of human migration.

- Geography: Mapping global migration patterns.

- Math: Analyzing statistics and data on new populations.

- Language Arts: Interviewing local immigrants and writing their stories.

- Ethics: Debating the moral questions surrounding borders and belonging.

This approach teaches students that problems in the real world are messy and interconnected. It teaches them collaboration, research, and critical thinking—skills that are far more valuable than just memorizing a date.

Pedagogical Approaches from Early Childhood Onward

The "less is more" philosophy starts from day one.

Early Childhood (Ages 0-6): Formal, academic schooling does not begin until age 7. Before that, the focus of "Early Childhood Education and Care" (ECEC) is play. That's it. The entire goal is to let children be children. Through structured, purposeful play, they learn crucial social skills, emotional regulation, and how to work in a group. The Finns believe this foundation of well-being and social competence is more important than learning to read at age 5.

Basic Education (Ages 7-16): When formal school starts, the pace is reasonable and humane.

- Shorter Days: School days are shorter, often ending around 1 or 2 PM, especially in the early grades.

- More Breaks: This is a big one. For every 45 minutes of instruction, students must have a 15-minute break. This isn't just a "passing period" to get to another class. This is 15 minutes to go outside, run around, clear their heads, and just be kids. Research shows this "distributed learning" is far more effective. The brain needs downtime to consolidate new information.

- Minimal Homework: Teachers believe that learning should happen at school. Home is for family, rest, and hobbies. Homework is light and usually for application or reading, not for hours of mind-numbing "busy work."

The entire pedagogy is built around a simple idea: a child who is rested, relaxed, and trusted will learn more deeply and effectively than a child who is stressed and sleep-deprived.

Assessment and Evaluation Without High-Stakes Testing

This is the part that boggles the mind of most outsiders. If you don't have standardized tests, how do you know if students are learning? How do they get into college? How does the country know its system is working?

The Philosophy and Practice of Assessment

In Finland, assessment is for learning, not for ranking.

There are no standardized tests in basic education, except for one optional test at the very end of high school (the Matriculation Examination) used for university admissions.

So, how are students graded?

- Teachers are the Assessors: Since the system trusts teachers, it trusts them to assess their own students.

- Formative Assessment: Assessment is constant, ongoing, and built into the daily learning process. It's formative, not summative. This means a teacher doesn't just give a giant test at the end of a unit (summative). Instead, they are constantly checking for understanding through conversations, projects, classwork, quick quizzes, and presentations (formative).

- Feedback, Not Just Grades: The goal of an assessment is to give the student feedback they can use to improve. It’s a diagnostic tool. The teacher's feedback is more like a coach's: "Okay, that part of your swing is perfect. Now, let's work on your follow-through." It's not a judgment; it's a guide.

Students do get report cards with grades (typically a number scale from 4 to 10), but that grade is based on a whole portfolio of work throughout the semester, not on one or two high-pressure exams.

Quality Assurance and System-Level Evaluation

So, how does the government know the system is working? They don't test every child. Instead, they use a clever, low-stakes method.

Each year, they take a small, random sample of students from different schools (maybe 10% of the student population) and test them in a specific subject. One year it might be math, the next it might be literacy.

Here’s the key: the results are anonymous. The scores are not used to praise or punish schools. They aren't published in newspapers to create "school league tables." The data is collected by the National Agency for Education only to see if there are any system-wide weak spots. If they notice that, for example, 8th-grade-math scores in rural areas are dipping, they don't blame the schools. They ask, "Does our system need to provide more resources or better teacher training for rural math?" It's a tool for improving the system, not for shaming students or teachers.

The Ecosystem of Student Well-being and Support: The "No Child Left Behind" Philosophy

This might be the true "secret" to Finland's success. Their commitment to equity isn't just a nice idea; it's a massive, funded, and deeply integrated ecosystem of support. They are obsessed with proactive, early intervention.

Holistic Support and Welfare Services

By law, every school must have a "Pupil Welfare Team." This team is not just for "problem kids." It’s a resource for everyone. This team typically includes:

- A school nurse

- A school doctor

- A school psychologist

- A school social worker

These professionals are in the building, full-time, and accessible to all students for free. If a student is feeling anxious, they can go see the psychologist. If they have a problem at home, they can talk to the social worker. If they are feeling sick, they see the nurse.

Furthermore, every single student, from 1st grade through university, receives a free, hot, and nutritious lunch every single day. This is a cornerstone of equity. It ensures that no child is trying to learn math while hungry. It removes any stigma, as everyone—teachers and students—eats the same meal together in the cafeteria.

The Three-Tiered Model for Learning Support

What happens if a student starts to struggle in, say, reading or math? In many systems, that student might just keep falling further and further behind until they fail the class.

In Finland, they have a "three-tiered" support system to catch that student immediately.

- Tier 1: General Support. This is high-quality teaching in the main classroom. The teacher differentiates their instruction to help everyone.

- Tier 2: Intensified Support. The teacher notices a student is struggling. That student is immediately given short-term help, often with a "special education teacher" in a small group, to catch up on that specific concept.

- Tier 3: Special Support. If the student has a long-term learning disability (like dyslexia) or continues to struggle, they are given a fully individualized learning plan, team-taught by the classroom teacher and a special education teacher.

This system is not stigmatized. In fact, nearly 30% of all Finnish students will receive some form of "special" or "intensified" support during their nine years of basic education. It's not seen as a failure; it's seen as a normal and smart part of learning. The goal is to fix the small problem before it becomes a big one. As a result, it is extremely rare for a student to repeat a grade.

A Different Kind of Success

The Finnish story is a powerful reminder that there is more than one way to "do school." Their system isn't perfect—in recent years, they have faced new challenges with budget cuts and a rise in immigration that tests their equity model. But their foundation remains unshakable.

They have proven that you can build an education system that produces world-class results without the high-stakes testing, the competition, the stress, and the long hours that so many of us accept as inevitable.

They traded the stress of competition for the power of collaboration. They traded a culture of inspection for a culture of trust. And they traded a narrow focus on academic scores for a deep, holistic commitment to the well-being of every single child. Finland’s success is a direct result of its core belief: that the best way to build a smart nation is to first build happy, healthy, and supported human beings.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Do Finnish students get any homework at all? Yes, but it's very different in scale and purpose. In the early grades, there is almost none. In upper basic education (grades 7-9), students might have around 30 minutes a night. The homework is usually designed for application (e.g., "Find an example of this concept in the real world") or reading, not for hours of repetitive drills. The belief is that home is for rest, family, and hobbies.

2. If there are no standardized tests, how do students get grades? Students absolutely get grades and report cards. But those grades are given by their teachers, who know them best. The grade is based on a wide "portfolio" of evidence gathered over the whole semester: class participation, projects, essays, presentations, and smaller quizzes. It's a holistic assessment of a student's understanding, not a single snapshot from one high-pressure test.

3. What about "gifted" or "talented" students? Does this system hold them back? This is a common concern, but the system is designed for differentiation. Because teachers have so much autonomy and smaller class sizes, they can easily tailor assignments. While the special education teacher might be supporting a small group that's struggling, the main teacher can give a more complex, in-depth project to the students who are flying ahead. The goal is "equity," which also means giving high-achievers the advanced challenges they need to thrive.

4. Is the Finnish system perfect? No system is. In the last decade, Finland has seen a slight decline in its international PISA test scores (though they are still near the very top). They face challenges, just like any other country, including how to best support a growing immigrant population and how to keep education funding high. However, their fundamental principles of equity and trust give them a strong foundation to solve these new problems.

5. Could a system like this ever work in my country? It's complicated. You can't just "copy and paste" the Finnish model. Its success is deeply tied to Finnish culture, which values social cohesion, trust, and modesty. However, the principles of the Finnish system can absolutely be an inspiration. Any school or district could choose to trust its teachers more, reduce the amount of standardized testing, give students more breaks, and invest more in early-intervention support and well-being. Finland shows us that these ideas aren't just a fantasy—they are a practical, proven path to success.